Changing international judicial, social and economic attitudes have resulted in debtors' prisons being made illegal across the globe. In 1976, this precept was enshrined Article 11 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which states "no one shall be imprisoned merely on the ground of inability to fulfill a contractual obligation."

In the US, imprisonment of debtors was eliminated at the federal level in 1833, leaving the issue up to individual states — although many were quick to follow Washington DC's lead, and several subsequent Supreme Court judgments seemingly reinforce the notion no American citizen should be incarcerated purely because they cannot pay debts.

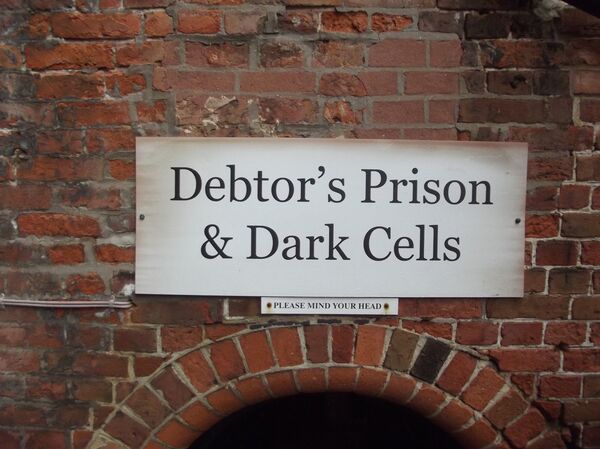

Dead Precedents

For instance, in 1970, the Court ruled in Williams v. Illinois extending maximum prison terms because an individual is too poor to pay fines or court costs violates their right to equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. The next year, in Tate v. Short, judges found it unconstitutional to impose a fine as a sentence, then automatically convert it into a jail term "solely because the defendant is indigent and cannot forthwith pay the fine in full."

Perhaps most notably, the 1983 ruling in Bearden v. Georgia, found the Fourteenth Amendment bars courts from revoking probation for a failure to pay a fine without first inquiring into a person's ability to pay, and considering whether there are adequate alternatives to imprisonment.

The case dated back to October 1980, when Bearden was sentenced to three years of probation and ordered to pay US$750 in fines and restitution for burglary and receiving stolen property, US$200 of which was due almost immediately. The defendant duly borrowed money from his parents to make a partial payment to the court, but rapidly fell behind when he was fired from his job a few weeks after his conviction.

The 1983 Supreme Court decision freed him — and set the precedent sentencing courts must inquire into a defendant's reasons for failing to pay a fine or restitution before sentencing them to serve time in prison, and that imprisoning someone merely due to their poverty was fundamentally unfair.

Or Did It?

A 2010 study of the 15 US states with the highest prison populations (Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia) conducted by the Brennan Center for Justice found all were home to jurisdictions that routinely arrested people for failing to pay debts or appear at debt related hearings. Such practices are not restricted to those 15 states, either — they can also be found in Arkansas, Colorado, Indiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee and Washington.

In brief, the "debts" leading to incarceration in modern America are monetary penalties imposed and enforced by municipal courts. Casualties of this phenomenon are disproportionately poor, and disproportionately black — after all, it is the extremely impoverished that typically cannot repay debts, and the latter often implies the former in the 21st century US.

Moreover, for many victims, imprisonment for debt can be a vicious circle without end — every time they miss a payment or court date, the court issues another warrant, and the individual is subject to arrest, jail, and additional fines and court fees, ad infinitum.

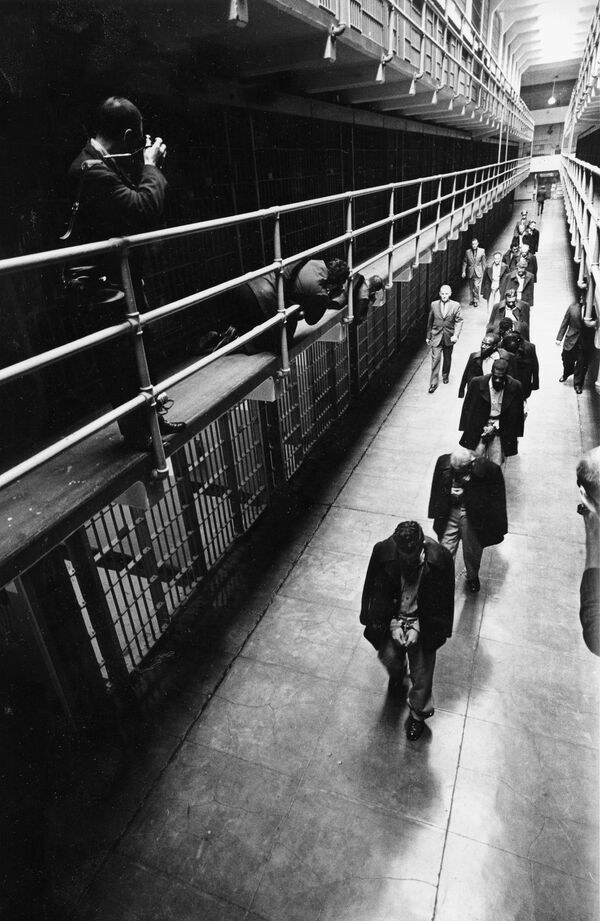

Walk into municipal courts in these states on any given day and there are likely to be row upon row of poor local residents awaiting punishment for failing to pay prior penalties. Some can expect further debt, others imprisonment — and those who fail to appear because they know they can't pay will be subject to arrest warrants. Later, whether, days, weeks, months, or even years subsequently, perhaps during a routine street or traffic stop, they will be arrested then jailed, perhaps fined even more too.

Dropping Pennies

The same year the Brennan Foundation for Justice conducted its examination, the ACLU issued In For A Penny, which highlighted many shocking instances of modern-day debt imprisonment.

For instance, in Washington, 'Lisa' (a pseudonym) saw her legal debts exceed $60,000 due to the state adding interest on unpaid liabilities. Though she hadn't committed a crime for almost a decade, she was arrested and incarcerated four times because of unpaid debt, including two occasions when she was not provided with an attorney before the judge imprisoned her. In one instance, she was jailed even though she told the judge she lacked the funds to pay her electricity bill.

In Georgia, Ora Lee Hurley was found to be in violation of probation and sentenced to a jail diversion facility for a minimum of 120 days or until she paid back a $705 fine owing from a drug possession conviction in 1990. She remained incarcerated for eight months after she completed the 120-day sentence, solely because she was unable to pay her fine.

These requests were all denied, with the court stating it would only release him if it received "all the money" he owed. In all, he served 330 days in jail. Had the judge followed state law requiring Webb be credited US$50 a day toward his debt each day he was incarcerated, his time in jail would've covered $16,500 in fines — over five times what he owed.

In Louisiana, Sean Matthews, a homeless construction worker, assessed US$498 in fines and costs when he was convicted of possession of marijuana in 2007. He was arrested two years later after failing to pay these fines, and spent five months in jail at a cost of more than $3,000 to the City of New Orleans.

In the same state, Gregory White, a homeless man arrested for stealing $39 worth of food from a local grocery store, was fined US$339, later converted to community service after he was jailed because he could not afford his fines. Failing to complete his community service due to an inability to afford the bus fare there, he spent a total of 198 days in jail.

The Why Of It All

The ACLU report makes clear imprisoning those who fail to pay fines and court costs is a relatively recent and growing phenomenon — the obvious question is, what accounts for this proliferation?

In brief, ever-reducing state incomes — driven by unfunded tax cuts and federal under-investment — have produced gaping budgetary holes, meaning states desperate for any and all sources of revenue increasingly look to court-imposed fines and fees to shore up their finances.

In theory, readily fining defendants and employing aggressive collection efforts should provide a steady stream of gains to state exchequers — but while it does undoubtedly provide money where none existed previously, there is little apparent official effort to gauge whether such a strategy is actually a net financial gain.

After all, imprisoning people is expensive, and as the ACLU's case studies amply demonstrate, jail terms for non-payment of debt can very easily end up costing far in excess of an original debt. Furthermore, incarcerating indigent individuals further reduces their ability to repay debts, and the disruption in their lives and the lives of their families and loved ones can lead to increased public costs when they are forced to use social welfare programs to survive.

Even when individuals do not end up in prison, aggressive collection efforts can render the policy equally ineffective, as issuing warrants, conducting hearings, and using collections agents and law enforcement officials to locate and detain debtors is cumulatively costly.