Ahead of this year’s Victory Day, Melikian shared with Sputnik the details of working with then US Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower and victory celebrations.

"I was in Supreme Headquarters Forward, Reims - now the Museum of Peace. I wasn't there the first, second and third days of the allied invasion of Europe. They [allied soldiers] are my heroes. They started it and I ended it with my message. I sen the message at 2:15 a.m. … They refer to me as the peacemaker. And I'm honoured."

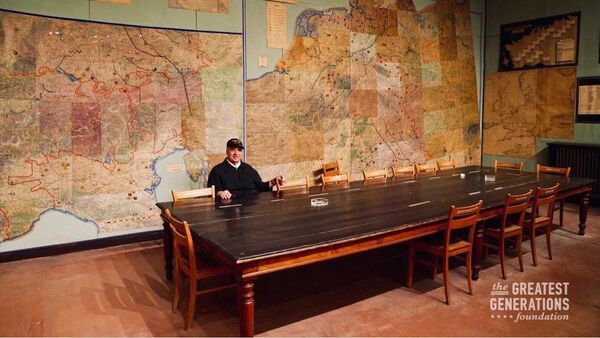

Melikian, who will turn 96 in July, is one of the 12 World War II veterans from the United States who will be heading to Moscow in May to participate in the events dedicated to the victory in the Great Patriotic War. The trip is sponsored by The Greatest GENERATIONS Foundation and will include visits to St. Petersburg and Volgograd.

Surrender Day

Melikian said he remembers the smallest details of what transpired when the signing to end the war took place in the Surrender Room, down the hall from the Radio Operators Room where he worked as an operator.

"They had a German admiral, Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, and they had a German general, General Alfred Jodl, and one interpreter sit on one side of the table, and on the other three sides were all the allies," Melikian said. "Among the allies was the Russian representative of Joseph Stalin and Marshal Zhukov, his personal representative. I can still close my eyes and see him and General Eisenhower walking and telling stories like brothers, their arms around each other's shoulders. He was Gen. Ivan Susloparov."

Melikian pointed out the German representatives insisted that Germany wanted to surrender only to the United States and the United Kingdom.

“Their idea was, can we just join forces and go against the Russians?" he said. "I have the copies when I was on duty in the Radio Operators’ Room that Gen. Eisenhower's response was, ‘Out of the question. No such thing will happen. You will surrender to the allied expeditionary forces, the British, the Americans and our allies and also the Soviet High Command.”

Melikian noted that he intends to bring copies of all the messages with him to the Victory Day celebrations in Moscow.

"When I was on duty, I happened to be given, before the surrender took place, those messages and to send them all over the world on May 7th at 11:01 p.m. Some people think it was 11:00 a.m., but I sent them. I should know. It was 11:01 p.m. the following day. I'm going to bring a copy of it to Moscow with me," he said.

Melikian went on to say that he sent a message at 2:15 a.m. and revealed why Eisenhower chose him to send the message to announce the ending of World War II in Europe.

"When… the Germans finally surrendered unconditionally to everybody, to the Supreme Headquarters and to all the allies, General Eisenhower sent General Walter Smith… not just to speak to the secret communications room through a little trap door, but to open the door and ask the three of us on duty at 2:15 in the middle of the night our names and our ages," Melikian said.

Melikian noted that the other two radio operators included a 36-year-old cigar-smoking sergeant from Texas and a 27-year-old man from South Carolina.

"So, General Eisenhower said: ‘I want Melikian to send these 74 coded words’ - it was in code because technically the war wasn't over until I sent my message - ‘I want him to talk about it the rest of his life.’ Here we are 75 years later, you and me are talking about it. That's how I was chosen to sit there and send the 74-word coded message.”

Melikian pointed out that he donated the original of that message and some 11-12 other messages leading up to Germany’s surrender and they are now displayed at Arizona State University.

"By this time, the Nazi Germans, Adolf Hitler and his wife of three days had committed suicide,” he said.

Melikian noted that Eisenhower asked the Soviet representatives to dig up the bodies and confirm that they were of Hitler and his wife.

“The Russians said to Eisenhower, no, no, we checked the teeth, we checked everything. Adolf Hitler is gone and his wife of a few days, his lady friend for 20 years or so, are dead and deceased. So that's how it ended,” he said.

Victory Celebrations in 1945

When asked what he felt when Germany surrendered and the victory was announced, Melikian said, "I had the feeling that, you know, I'm gonna make it."

"I'm gonna go home after roughly three years of being away from home in one piece. It looks like I'm gonna make it okay," the veteran said.

Melikian also shared how those who were at the Supreme Headquarters in Reims celebrated.

"The French had three or four miles in Reims, Supreme Headquarters Forward. They had three or four miles of Champagne," Melikian said, adding that they were the best kinds of champagne, worth $220 a bottle, in tunnels under the city. "The Germans, the Nazis never knew about that. The moment we arrived and the surrender took place, they said to the Americans, the British, everybody, all the allies, ‘Help yourself. Bring back the empty champagne bottle, we’ll refill it.’"

This May, Melikian will head to Russia along with another 11 US veterans to share in the 75th victory anniversary celebrations with the Russian people.

"I can't tell you how delighted and honoured I am," Melikian said. "I'm so proud of what the Russians did. We were partners. We couldn't be closer. And I think as partners, we prevented the Nazis from taking over the world. Adolf Hitler had plans for the whole world to speak Deutsch, we'd be speaking in German today. Many of us, thank God, together as partners, we did not allow that to happen."

Melikian also pointed out that he does not believe in war and only believes in peace.

"That's why they call me the peacemaker… I don't believe in war," he said. "These are the words that Eisenhower says in his opinion of war: "I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity." I agree with that. No more wars, no more killing. Let's talk each other's languages. Let's talk to each other."

Working With Eisenhower

Melikian noted that the United States had a system of numbers draft and after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor his number was called up.

"They took me to camps for basic training and they gave me examinations. And they said they think I would be an excellent high-speed radio operator," he said. "They sent me to the University of Illinois, and I, in uniform, took college courses, which came in handy later on. And they also sent me to Ripon College, Wisconsin, 75 miles north of Milwaukee, in uniform like cadets. We were almost junior officers, but we were still cadets."

Melikian said he then went to Europe on the Queen Mary without being protected by a military convoy.

“The German submarines were very successful in sinking many, many ships in the Atlantic," he said. "So, instead of going with a bunch of destroyers protecting us, I went alone on the Queen Mary to Scotland with 12,500 soldiers plus 500 nurses on the ship. No convoy. But we were faster, faster than any submarine, and sometimes at certain angles we were even faster than the torpedoes," he said.

Melikian explained the trip lasted five days, instead of two months with convoys and crossed one day in high tide.

"We zigzagged across to Scotland… From there they took me to Birmingham, and from Birmingham to Southampton. And as the war progressed in Europe, they ultimately took me to the outskirts of Paris…We went to… that was called, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces Rear outside of London. Rear. I joined Eisenhower at Supreme Headquarters Main, just outside of Paris in Versailles," he said.

Melikian noted that he had worked with Eisenhower every day for two years, morning and night.

"When he went to the different army groups, one or two of us, radio operators, had to go with him," he said. "Whenever Eisenhower went someplace, one or two of us had to go in his limo if it wasn't too far, or we would have tracks to put his limo on a train. And the train would carry Eisenhower and his group to talk to different allied generals. So we would always have to be where he was because he had no other way of communication. When he took an airplane, one or two of us had to go with him to visit the different military army groups."

"I can see his arm around Walter Bedell Smith. General Smith. He was the only general that drove his own car to other generals, Americans, British Canadians or Australians, Polish, whatever would sit in the back and have a chauffeur drive the Cadillac," he added. "So, I can still see him and Ivan Susloparov, like I told you earlier, joking and telling stories and being very close friends. They were people-oriented persons."

Melikian pointed out that Eisenhower himself was a tough but honest human being.

"He could be firm, he could be strong, but he never lost his temper… whatever he had to do," Melikian said. "He would say, if there's anything wrong in writing, blame me. I'm the one that started the invasion on the Western Front to help the Russians as partners, which we were, we were partners, as we all know, in World War II."

Moreover, Melikian continued, Eisenhower never used bad language.

"George Patton, unfortunately, was a very powerful, opinionated general that would use four-letter words and all. No, you would never hear that from Eisenhower. He never used that language," he said.

But Melikian remembered, however, one instance when Eisenhower would not stop cursing for more than a day.

"Four or five days before the German admiral and the German general came to surrender, they took him [Eisenhower] to a concentration camp. I forgot the name of the concentration camp… It was originally built not for the Jews, a terrible genocide that he committed, but it was for captured Russian soldiers originally," he said. "When they took General Eisenhower and showed him… that concentration camp for one and a half days, he wouldn't stop cursing for the first time. We had to slow him down. We had to slow him down for a one and a half days. He couldn't control man's inhumanity to man. He couldn't. We had to control him and calm him down."

Melikian also noted that when General Walter Bedell Smith came home after World War II, he studied Russian, learned it fluently, and went as United States ambassador to the Soviet Union in those days.

A ‘Very Interesting’ Post-War Life

Melikian said he was born in 1924, an only child, and retired in the United States as an honorary brigadier general.

"I have a very interesting, full life, as you know. I'll be 96 in about 100 days. Each day is a gift to me," he stated.

Melikian said he met his wife Emma after the war when he had already graduated as a lawyer and became a judge in New York City for a few years.

"We met and got married in 1954," Melikian said, adding that he and Emma met in the Russian Tea Room, a famous restaurant in New York City.

The veteran revealed the secret of such a long, happy marriage.

"I've been married to the same woman for sixty-five years. You know how it lasted that long? Why? In English, two English words. ‘Yes, dear’," he shared. "You have to continue saying, ‘yes, dear.’ And the marriage will last sixty-five years."

Melikian and Emma have three sons in their early 60s and a daughter in her early 50s. They also have three grandchildren.

The veteran noted that this year he will travel to Russia without his wife, but recalled that the two were there in 1979 when the then the Soviet Union was getting ready for the Olympics. Melikian said they visited various cities and enjoyed every moment of it.

Melikian said that at his age he still walk, drive a car and frequently goes to different places.

"Once in a while I use a cane, once in a while I use those four wheels that you put your weight in or slip or fall because the worst thing that can happen to anybody at 95, 96 to 99 years of age is to have an accident. Once you have an accident at that age, that's the beginning of the end," he said.

Melikian noted that he is also busy giving lectures to various veterans’ groups about how World War II ended.

"All different veterans’ groups that want to know why, what happened to their grandfathers and their uncles if they were in the European theater, because that's where I was, in the European theater," he said. "And then I take questions, I take questions the last fifteen or twenty minutes. Anything they want to know about World War II."

Moreover, Melikian revealed that he is writing a book about what he referred to as “the messenger.”

"That's me," he said. "The other boys are my heroes with the Russians doing the heavy fighting with heavy losses. They're my heroes."

Melikian Centre

Arizona State University houses the Melikian Center for Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies, founded in 1984 and was named after the Melikian family in 2007. The centre provides instruction in various languages, such as Turkish, Armenian, Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Uzbek, and others.

"We believe in education and in learning of languages. We believe if you speak in each other's languages, maybe you don't have to go to war," Melikian said.

The veteran noted that interest among young people in learning these languages is growing.

"It's increasing now. More people believe, ‘Let them talk in each other's languages. Not in one language or the other, not understanding each other," he said. "And let's not have any more wars. Enough killing."

It is amazing to see Americans that come out of villages and take languages like Uzbek, Farsi, like Ukrainian, Polish and other Eastern European languages, the veteran said.

The centre does not go into politics, it only teaches languages, the history of those languages and culture, Melikian added.