Researchers are about to unveil a new technology that would promise better chances of capturing the sight and analysing the features of faraway exoworlds, namely planets orbiting distant stars, as announced by the University of California, Santa Barbara, earlier this month.

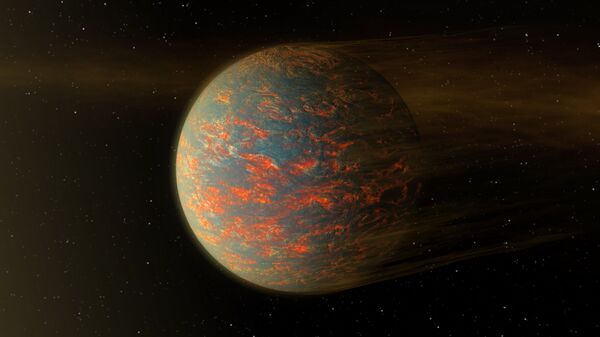

Most of the planets found so far have been gas giants like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, or Neptune that are close to their stars, since they are the easiest to detect due to their enormous size.

However, a new observational method - dubbed spectroscopy - would allow scientists to measure the atmospheric composition of not solely the giants, despite this also being a challenging task, but of smaller rocky worlds, including ones in the habitable zones of their stars, like our life-sustaining planet Earth in the Sun’s vicinity.

The method presupposes that the light passing through the planet’s atmosphere can be broken down into separate colours - an indication that chemicals are present in the atmosphere.

Per Benjamin Mazin, whose lab is leading UC Santa Barbara’s part of the research, taking a picture of a nearby solar system is “one of the most technologically challenging things we do in astronomy”, mainly because Earth’s atmosphere "royally messes up the picture”. “It’s like trying to take a picture through a windshield that’s getting blasted with rain", the researcher said in a statement.

The technology promises to enable astronomers to map biosignatures - namely gases produced by life, such as oxygen or methane.

While this technology can be used for a variety of different exoplanets, the primary goal is to be able to characterise Earth-sized planets with temperate conditions that could be habitable, even if these appear to be tiny dots scattered to the sides of our planet.

Central to new top-notch technology being developed by UC Santa Barbara, just one of an array of university teams that the Heising-Simons Foundation is currently supporting, is a new kind of promising photon detector called a microwave kinetic inductance detector (MKID), which has been integrated with the Hawaii-based 8-metre (26-foot) Subaru Telescope. This also uses Heising-Simons Foundation funding to develop the necessary data processing algorithms.

"I feel there is no more compelling problem to work on. Learning about nearby planets tells us a lot about ourselves and our place in the universe", Mazin commented.

Earlier this month, Extreme-ultraviolet Stellar Characterisation for Atmospheric Physics and Evolution (ESCAPE) was picked by NASA as one of the two most promising missions geared toward detecting life in the far corners of the solar system.

While ESCAPE is not unique in its objective of observing and evaluating the habitability of exoplanets, the means through which it gathers data are uncommon. Rather than directly seeking out an exoplanet itself, the satellite will instead focus on the levels of radiation produced by nearby stars.