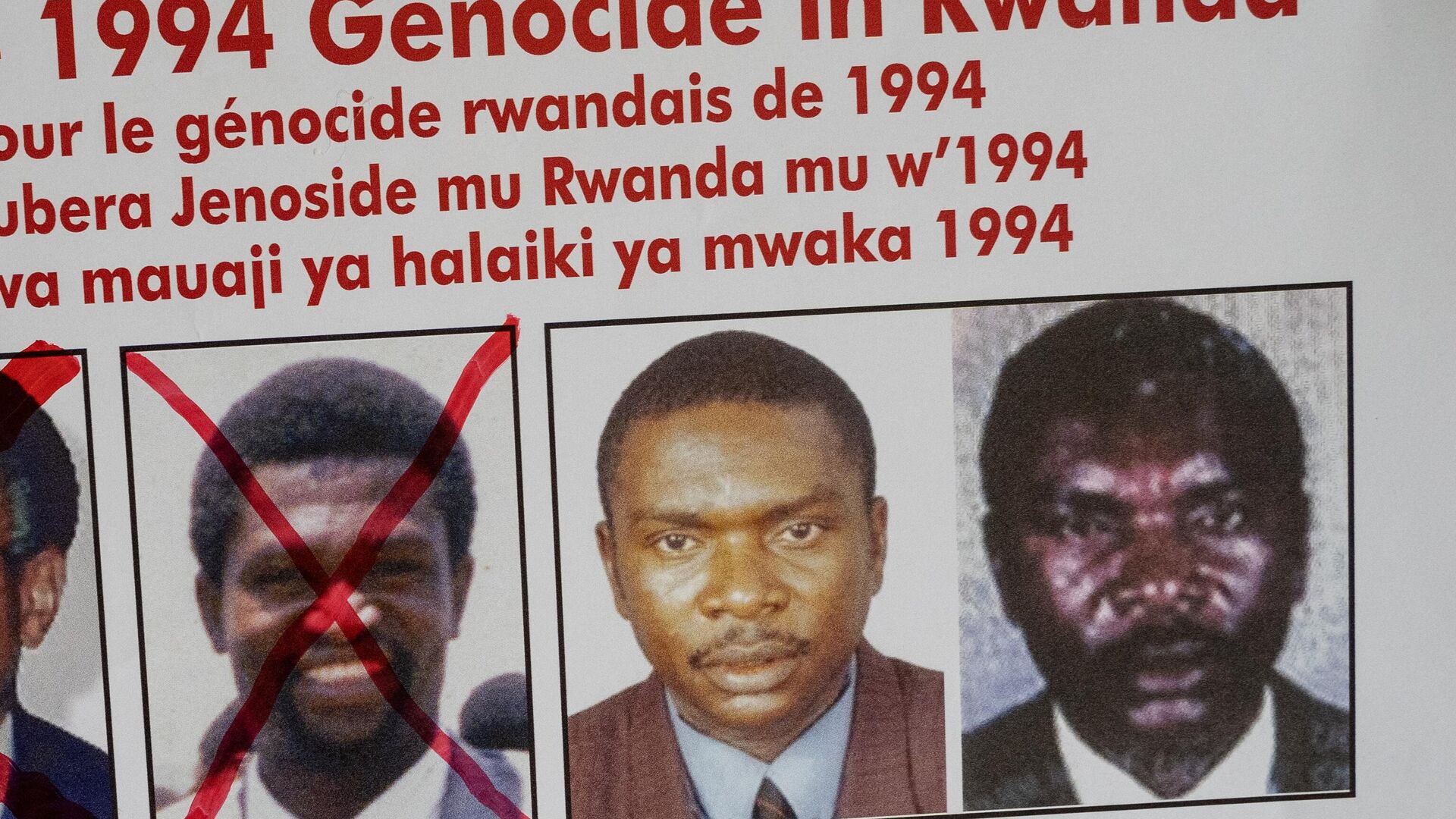

Rwandan Genocidaire Protais Mpiranya Confirmed to Have Died in Zimbabwe in 2006

21:17 GMT 12.05.2022 (Updated: 20:11 GMT 19.10.2022)

Subscribe

The fate of one of the central figures of the Rwandan Genocide has finally been ascertained: according to United Nations investigators, Protais Mpiranya has been dead since 2006, his body lying in a Harare grave under a false name.

Serge Brammertz, the UN prosecutor who led the 20-year manhunt, told The Guardian that finding Mpiranya’s body "provides the solace of knowing that he cannot cause further harm.”

Mpiranya was indicted in 2002 by the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, a court established in Tanzania by the UN Security Council in the wake of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide to prosecute and judge those responsible for the mass killings. He was charged with genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, complicity in genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

As commander of the Rwandan presidential guard at the time of the genocide, Miranya, an ethnic Hutu, played a central role in many of the targeted killings, including the assassination of Rwandan Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana and Information Minister Faustin Rucogoza, and the capture, torture and execution of 10 Belgian peacekeeper soldiers from the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR).

The massacre of ethnic Tutsis by the Hutu government and its allies began following the downing of then-Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana’s aircraft, killing him and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira, also a Hutu, on April 6, 1994. The party responsible for shooting down the passenger jet was never determined, but Hutu extremists blamed Tutsi rebels, as well as moderate Hutu leaders who had recently signed a peace treaty with the Tutsis to end a civil war.

This file photo taken on April 04, 2014 shows human skulls preserved exhibited at the Genocide memorial in Nyamata, inside a Catholic church, where thousands were slaughtered during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

© AFP 2023 / Simon Maina

During the years of Belgian colonial rule, a divide-and-conquer policy was used to turn the Hutus and Tutsis against each other by claiming that the Hutus were indigenous to the region and that the Tutsis were invaders who sought to displace them. This created an atmosphere of suspicion and hatred that drove several conflicts in the region, including in neighboring Burundi, and would indirectly spark the Congo Wars to Rwanda’s west.

Within hours of Habyarimana’s death, leaders of the radical Hutu Power movement began assassinating Tutsi leaders and moderate Hutus using “kill lists” already drawn up by Mpiranya and others, and soldiers and police established checkpoints the next day and conducted sweeps to check people’s national ID cards, which indicated the bearer’s ethnicity. Those who were Tutsi were executed. Later, gangs and mobs were organized and set upon the local population.

By July 1994, up to 1.1 million people, including 800,000 Tutsis, or two-thirds of all Rwandan Tutsis, had been killed, along with one-third of the 30,000-strong Twa people. Only the steady advance of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Tutsi militant group, and its capture of the capital of Kigali ended the killings.

In May 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron met in Kigali with Rwandan President Paul Kagame, who led the RPF at the time of the genocide, but did not apologize for France’s support for the Rwandan government at the start of the genocide. Macron did acknowledge “the magnitude of our responsibilities.”

President Emmanuel Macron of France hosted Rwanda's President Kagame at the Elysee Palace last year as he sought to thaw relations

© AP Photo

Mpiranya fled south ahead of the RPF victory, seeking refuge in Zimbabwe, where he became a vital consultant for President Robert Mugabe after the Second Congo War broke out in 1998. In that conflict, also called “Africa’s World War,” Zimbabwe was among the nations that rallied to the defense of Congolese President Laurent-Desire Kabila and his Hutu allies. Arrayed against them were Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and a series of allied militias aiming to destroy the Hutu power base in the eastern Congo, into which they had retreated after the RPF victory and begun launching attacks into surrounding areas.

“That the Zimbabweans, at least elements of the authorities, knew he was in Harare is obvious,” a senior official involved in the investigation told the Guardian. “He was even seen meeting with Zimbabwean officials. Of course, he was trying to hide his identity from the public, but the entire reason he went to Zimbabwe is because of his relationships there.”

According to UN investigators, Mpiranya lived in Zimbabwe under a fake name until his death in 2006, caused by a heart attack brought on by tuberculosis. He was 50 years old. His grave was overgrown and he was buried under that fake name.

As early as 2012, Rwandan daily The New Times reported that the ICTR “had always believed” Mpiranya was hiding in Zimbabwe, noting the Belgian government was the first to make the accusations a year prior.

After they tracked his grave down using a critical lead found on a confiscated computer that included a hand-drawn design for Mpiranya’s tombstone, his body was exhumed and DNA tested. The results were unmistakable: it was him.

Theoneste Bagosora, who was the Rwandan defense minister at the time of the genocide and its supreme architect, died last year in a Malian prison. Bagosora was serving a 35-year sentence after being found guilty of crimes against humanity.