21 Years Ago Today: US Rips Up ABM Treaty With Russia, Starting Slow Slide Toward Current Crisis

13:36 GMT 13.12.2022 (Updated: 15:44 GMT 13.12.2022)

© AFP 2023 / STEPHEN JAFFE

Subscribe

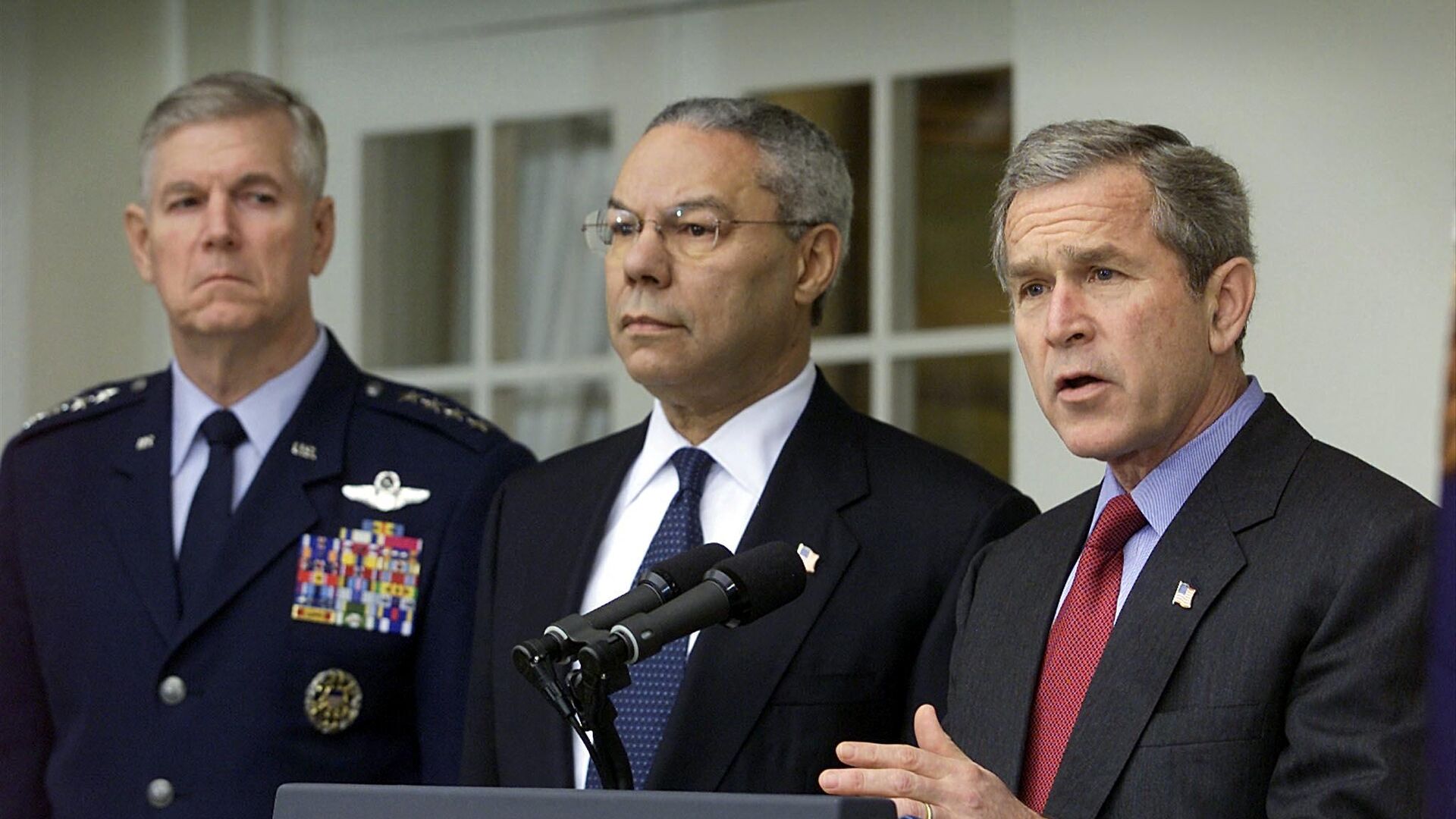

Tuesday marks the 21st anniversary of the decision by then-US President George W. Bush to quit the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, a landmark 1972 agreement which limited the anti-ballistic missile capabilities of the US and the USSR (and later Russia). The move became the canary in the coalmine of trouble in relations between Russia and the US.

“I have concluded the ABM Treaty hinders our government’s ways to protect our people from future terrorist or rogue state missile attack,” US President George W. Bush said, speaking to reporters at the White House Rose Garden on December 13, 2001. “Today I have given formal notice to Russia…that the United States of America is withdrawing from this almost thirty year old treaty,” he said. Six months later, on June 13, 2002, the agreement was history.

The ABM Treaty, signed by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and US President Richard Nixon in May 1972, limited Moscow and Washington’s ability to build ballistic missile interceptors, and was designed to slow the expansion of the superpowers’ arsenals of nuclear warheads and delivery systems, and to prevent either country from trying to gain an advantage over the other which would upset the global strategic balance.

What Did Russia Say and Do at the Time?

Vladimir Putin, then just starting his first term as president, told his US counterpart that Moscow was not surprised by the US decision, but considered the move an “erroneous one,” given that the treaty had served as a “cornerstone” of world security and stability.

A month before that, on November 13, 2001, during a state visit to the US, Putin informed his hosts that Russia and the US had “different points of view about the ABM Treaty,” but would “continue dialogue and discussions...to develop a new strategic framework that enables both of us to meet the true threats of the 21st century as partners and friends, not as adversaries.”

Publicly, Washington maintained at the time that terrorists, or so-called “rogue states” like North Korea or Iran (which the Bush administration labeled as members of an "Axis of Evil") might create or obtain missiles to attack America or its allies.

Behind the scenes, Moscow suspected that the US was bluffing, and that the true purpose of new expanded American missile defenses would be to disarm Russia’s nuclear deterrent, which at the time was one of the only remaining factors standing in the way of total US global hegemony and the "new world order" declared by President Bush’s father, George H.W. Bush, in late 1991.

To prove it, Putin and Sergei Lavrov (who became Russia’s Foreign Minister in 2004), concocted a diplomatic maneuver to test Washington’s sincerity. In July 2007, on the sidelines of a G8 summit in Germany, Putin threw Bush a curve ball by proposing the deployment of a joint missile defense system in Azerbaijan. The plan outlined the use of an X-band radar in the post-Soviet republic to guide anti-missile interceptors, and, if approved by the US, would confirm that Washington’s missile shield plans really were aimed at so-called “rogue states,” not Russia.

“This will make it impossible – unnecessary – for us to place our offensive complexes along the borders with Europe,” Putin said, referring to US plans at the time to create a series of radar systems in the Czech Republic, along with missile interceptors in Poland.

Right to left: U.S. President George W. Bush, Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Angela Merkel out for a walk in Heiligendamm. June 7, 2007. File photo

© Sputnik / Dmitri Astakhov

/ The Bush White House politely declined the proposal. “This is a serious issue and we want to make sure that we all understand each other’s positions very clearly,” Bush told Putin.

In April 2008, at a meeting in Sochi – their final one before Putin stepped down as president and became Russia’s prime minister, and less than a year before the end of Bush’s presidency, the leaders failed to come to an agreement on missile defenses. “This is an area we’ve got more work to do to convince the Russian side that the system is not aimed at Russia,” Bush said, speaking to reporters. “I want to be understood correctly. Strategically, no change has taken place in our…attitude to US plans,” Putin responded.

(Re)Birth of Russia’s Hypersonics Program

Still recovering from the catastrophic geopolitical and economic fallout of the collapse of the USSR, and watching closely as NATO expanded into Eastern Europe in several waves between 1999 and 2004, Moscow appeared to have gained the vague impression that behind the US rhetoric of friendship and partnership, Washington had not truly given up on its vision of Russia as an adversary after 1991.

In September 2020, during a meeting with Gerbert Efremov, the former director and chief designer at the legendary NPO Mashinostroyenia rocket design bureau – responsible for the creation of some of Russia’s new hypersonic weapons, Putin revealed that the US withdrawal from the ABM Treaty was the singular moment which prompted Moscow to develop these cutting-edge armaments, which the USSR had tinkered with at the twilight of the Cold War.

“America’s withdrawal from the ABM Treaty in 2002 forced Russia to start developing hypersonic weapons. We had to create these weapons in response to the deployment of the US strategic missile defense system, which would have been able to neutralize and render obsolete our entire nuclear potential,” Putin said. Russia’s hypersonic designs, gave Russia, for the first time in its modern history, “the most modern types of weapons, superior in terms of their force, power, speed and, very importantly, in terms of accuracy, compared to all which existed before them and exist today,” Putin said.

Putin returned to the fateful US decision on the ABM Treaty in remarks in October 2021, saying that Washington’s move had opened the Pandora’s box of a new global arms race, and demonstrated that America was not looking to defend itself, but trying to “receive strategic superiority, effectively eliminating the nuclear potential of a potential rival.”

“What should we have done in response? I have spoken on this subject many times,” Putin said. “We could have either created a similar system, which would cost immense amounts of money, and it would be unclear in the end if it would work effectively or not. Or we could have created a different system which would definitely overcome missile defenses. I said that we would do this. The response from our American partners was that ‘our missile defenses are not directed against you, do whatever you want, we will proceed from the fact that your projects are not against us.’ We built our systems. What claims do they have against us now? Now they don’t like them,” Putin said.

Russia unveiled a series of new strategic weapons systems in 2018, with the arms, including the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, the Kinzhal aero-ballistic air-to-surface missile, the Sarmat ICBM, and the Poseidon nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed autonomous torpedo, designed to assure that even if Washington did successfully build a missile shield, Russia would still be able to retaliate to hypothetical US aggression.

What Other Treaties With Russia Has the US Unilaterally Ripped Up?

The ABM Treaty wasn’t the only security agreement with Moscow that Washington had unilaterally quit in recent years. In 2018, the United States pulled out of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty – an agreement banning the deployment of ground-based strategic missile in the 500-5,500 km range. In 2020, the US left the 1992 Treaty on Open Skies – which allowed 35 partner nations to perform military reconnaissance overflights over one another’s territory using specialized aircraft. Moscow was forced to follow suit in 2021.

28 January 2022, 23:33 GMT

What’s Left?

In January 2021, the incoming Biden administration agreed to renew the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), an arms control treaty which obliges the two countries to reduce their nuclear arsenals to between 1,700 and 2,200 operationally deployed warheads. The Trump administration intended to let the clock run out on the agreement, demanding that China’s modest nuclear arsenal be added to any strategic treaties. The Biden administration agreed to extend it to February 2026.

With the collapse of the ABM Treaty, the INF Treaty and the Treaty on Open Skies, New START is now the last major security treaty between Russia and the United States. But there are two other international agreements, the Outer Space Treaty and the Chemical Weapons Convention, to which both Moscow and Washington are parties, whose future has also been threatened by US behavior.

On December 7, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a Russian resolution against the placement of weapons in outer space, urging all members and particularly nations with “space capabilities” to uphold, “as appropriate, a political commitment not to be the first to place weapons in outer space.”

The resolution was merely a political declaration, and no means exist to enforce it. However, in 2008, Russia and China recommended a binding agreement – the Proposed Prevention of an Arms Race in Space (PAROS) Treaty – outlining specific measures to ban the deployment of space-based weaponry, anti-satellite spacecraft and other technologies which could be used for military purposes, in orbit. Successive US administrations have spurned the proposed treaty, and in 2019, the Trump administration formalized the creation of a new branch of the US military called "Space Force," signaling that Washington will has no plans to rein in its space-based military activities.

Space Force, and other US efforts to militarize space (such as the deployment of large networks of dual-use commercial communications and surveillance satellites), maybe be a violation of the Outer Space Treaty, a 1967 agreement signed by 112 countries, including the United States, which prohibits the deployment of weapons of mass destruction in space, restricts the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes, and forbids military bases, weapons testing and military exercises in space.

US scholars of international law have outlined a series of arguments on how the US may be in violation of the Outer Space Treaty, ranging from former President Trump’s statements about the need to assert US “dominance” in space, to Washington’s designation of space as a new “war-fighting domain.”

“These assertions violate major Outer Space Treaty principles, including the prohibition of establishing sovereignty in space and using space only for peaceful purposes. The creation of the US Space Force can also be seen as a ‘threat of force’ based on its history of aggressive and dominant remarks,” explained Rachel Harp, an associate member of the University of Cincinnati Law Review.

Space Force General Claims China Moves 'Twice the Rate' of US in Space Race, May Overtake It by 2030

6 December 2021, 23:27 GMT

Finally, there is the Chemical Weapons Convention, another arms control treaty to which both the United States and Russia are parties, but where question marks remain regarding Washington’s commitment to the agreement. While Russia completed the destruction of the last of its Soviet-era chemical weapons in September 2017, under the watchful eye of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, the United States has consistently revised deadlines to destroy its own chemical arms stockpiles.

Washington originally promised to eliminate the last of its deadly chemical agents by 2012, but now promises to do so by late 2023. With nearly 650 tons of chemical agents and munitions remaining in its arsenal, the United States now has the largest declared chemical weapons stockpile in the world.