Why is the US Militarizing the Philippines?

14:32 GMT 16.02.2023 (Updated: 15:17 GMT 17.02.2023)

© AFP 2023 / TED ALJIBE

Subscribe

The Philippine Army announced Wednesday that it will be holding its largest joint exercises with the US since 2015 this spring. This comes on the heels of plans by Washington to expand its access to the Asian nation’s military bases. What’s motivating this surge in military activity, and what are the Pentagon’s ultimate aims? Sputnik explains.

The upcoming US-Philippines Exercise Balikatan (lit. "shoulder-to-shoulder" in Tagalog) drills, set to take place between late April and June, will be the largest in years, Philippine Army chief Romeo Brawner Jr. has confirmed.

“Activities will be spread throughout the country. A lot of these will be done in our traditional exercise areas such as Fort Magsaysay, we also have Tarlac and HADR [Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief, ed.] activities in the northern part of the country down to the south,” the general said, speaking to reporters on Wednesday.

“All these exercises we are doing are in response to all types of threats we may face in the future, both man-made and natural,” the commander added.

Brawner said the exact numbers of US and Philippine troops taking part in the exercises is still being finalized, but noted that they “will be bigger than the past year’s exercise”– which involved some 8,900 US and Philippine servicemen, plus 40 Australian Defense Force observers. Last year’s Exercise Balikatan drills were themselves the biggest of their kind since 2015.

US diplomats characterize the annual exercises as a keystone to preserving the “peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific Region,” and a demonstration of the “strength and resolve of the Philippine-US alliance” in “pursuit of our shared commitment to mutual defense in a free and open Indo-Pacific.”

FOIP

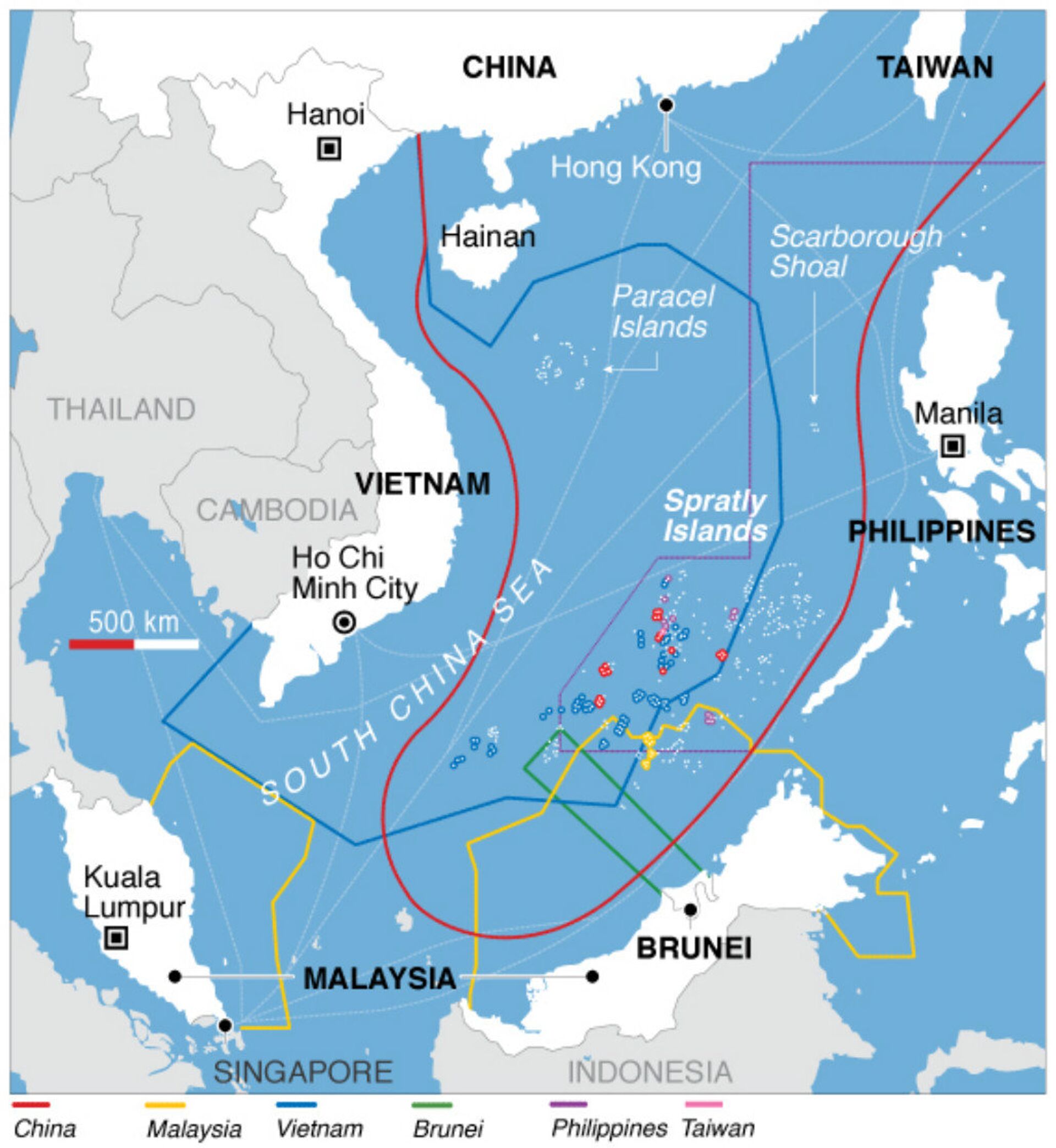

“Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” or FOIP, is the key term here. Officially codified in US State Department jargon in 2019, it refers to Washington’s strategy of directly challenging Beijing’s territorial claims in the East and South China Seas, and other military and diplomatic efforts to contain Beijing near its home waters. The US took an active position in the South China Sea territorial dispute in 2010, when then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton characterized it as a matter of US “national interest,” and began a push to shore up bilateral alliances with regional partners, including the Philippines. China, which has been working with the region’s nations to try to resolve territorial disputes on a local level since 2002, has repeatedly called on Washington to butt out of the dispute.

Strategic Implications for China

The Philippines was a stalwart US ally against the Soviet Union and China throughout the Cold War, with Washington backing strongman President Ferdinand Marcos against communist infiltration (the country experienced a decades-long communist insurgency, which was supported by Beijing until the mid-1970s). In return, Manila guaranteed the US access to several major military bases, including:

Cesar Basa Air Base and Fort Magsaysay outside Manila

Mactan-Benito Ebuen Air Base, situated in the central province of Cebu

Antonio Bautista Air Base on Palawan, a key strategic western archipelago straddling the South China Sea

Lumbia Airfield in Misamis Oriental province in the country’s south.

Crucial China Choke Point

The Pentagon’s interest in these and other military facilities in the Philippines outlived the Cold War. Even a cursory glance of a map of Southeast Asia reveals the Philippines’ geostrategic significance to the US against China, including efforts to counter the growing size, range, and sophistication of the People’s Republic’s Navy and Air Force. The stars in the map below show, from top to bottom, the natural choke points formed by the Philippines’ geography vis-à-vis Taiwan (the two are separated by the Luzon Strait), and Palawan, which can block Chinese Navy and commercial ships’ entry into the Sulu Sea northeast of Malaysia via the Mindoro and Balabac Straits.

Map of Southeast Asia (green) showing strategic maritime choke points which could cut off China's access to the world's oceans via the Philippines in the event of a US-China conflict.

© Photo : Modified Wikipedia map.

Along with South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan in the north and Singapore and Thailand to its south, the Philippines thus forms a key natural barrier hemming in the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s access to the wider Pacific and Indian Oceans.

First and Second Island Chains

The concepts outlined above, and the strategy for "containing" China in its home ports, aren’t new. In 1951, future Eisenhower Secretary of State John Foster Dulles outlined the "Island Chain Strategy." According to the scheme, Japan (including the US base-ridden island of Okinawa), Taiwan, the Philippines, and the northwestern portion of the island of Borneo constitutes the "First Island Chain," while the area between Yokosuka, Japan, Guam, and on down to eastern Indonesia constitutes the "Second Island Chain."

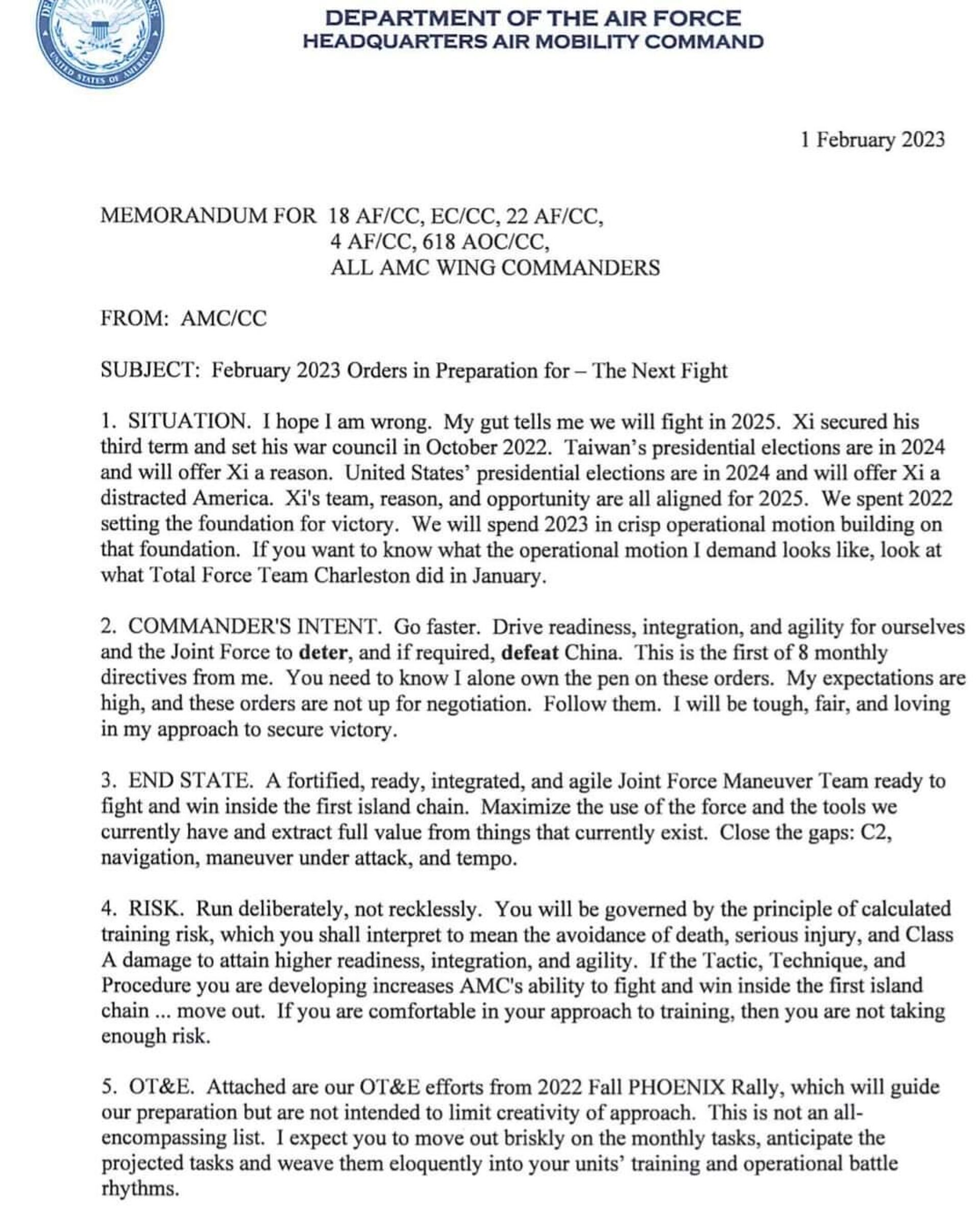

Over 70 years after its inception, the Island Chain Strategy has not lost a bit of relevance in the minds of Pentagon planners. Last month, US Air Force Mobility Command chief Gen. Mike Minihan used the term in a leaked memo predicting that US-China tensions would escalate into a hot war in 2025.

“A fortified, ready, integrated, and agile Joint Force Maneuver team ready to fight and win inside the first island chain” is the “end state” for US training going forward, Minihan wrote. “If the Tactic, Technique, and Procedure you are developing increases AMC’s ability to fight and win inside the first island chain, move out. If you are comfortable in your approach to training, you are not taking enough risk,” Minihan emphasized.

Excerpt from Air Force General Mike Minihan's leaked memo to subordinates predicting a US-China war in two years.

© Photo : Mike Minihan

US Missile Bases

While the Island Chain concept isn’t new, Washington’s plans for the unprecedented nuclear militarization of the region are a fresh addition. In 2019, shortly after ripping up the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia, Washington immediately began research and development on a new generation of ground-based intermediate-range ballistic missiles, and announced plans to place them in Asia, with South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines seen as key possible deployment points.

A 2019 study by Stratfor, a highly influential US think tank, laid bare the strategic importance of these potential Asian missile bases for US strategy, with land-based Tomahawk cruise missiles and ballistic missiles with a range of 4,500 km effectively threatening to blanket the entirety of North and Southeast Asia, including all of China’s major population centers. The Philippines plays a central role in these calculations. Any Tomahawks stationed in the country would be able to threaten the entire South China Sea, the First Island Chain line all the way to Japan, and many Chinese coastal cities. The longer-range ballistic missiles, meanwhile, would cover not only all of China, but most of Russia east of the Urals, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, and the Pacific all the way to Hawaii.

Potential operational range of US Tomahawk cruise and intermediate-range ballistic missiles if deployed near China in a map by Stratfor.

© Photo : Stratfor

Power Politics

In 2019, then-President of the Philippines Rodrigo Duterte announced that he would “never” allow the US to put nuclear-tipped missiles in his country, emphasizing he had no intention of allowing Washington to turn his country into a warzone with China. Duterte cautioned all countries in the region “to exercise prudence and not allow” the deployment of US missiles on their territory. “That would not serve the national security interest of these countries,” he said.

During his time in office between 2016 and 2022, Duterte carefully walked a tightrope in trying to balance traditional ties with Washington, and building new ties with Beijing and Moscow (last year, for example, the Philippines was forced to scrap a $215 million Mi-17 helicopter deal with Russia amid heavy pressure from the US). Duterte also repeatedly threatened to tear up a military agreement with the US permitting American forces to operate in the country over “insults” to the Philippines’ sovereignty. But forcing out US troops, stationed in the country since 1945, is apparently easier said than done. In 2018, he warned that the Philippines’ military wasn’t ready to commit “suicide” in an “unnecessary” and “needless” conflict with China. “If I were a general, and you order me to go there, commit suicide with my troops, I will tell you ‘f*** you. Why do I have to do that?’” the president asked.

After his inauguration last year, new Philippine President Ferdinand Bongbong Marcos Jr. expressed openness to continuing Duterte’s line of maintaining a high-wire act balance between Washington and Beijing, and finding ways to resolve territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea. In the months since, Marcos’ stance on China has seemed to harden, with the leader vowing not to abandon “even a square inch” of land in the South China Sea dispute, and saying he couldn't see a “future for the Philippines that does not include the United States.”

During a visit to the Philippines in November, Vice President Kamala Harris assured Marcos that Washington “stand[s] with” Manila “in defense of international rules and norms as it relates to the South China Sea,” and that any “armed attack on Philippine armed forces, vessels or aircraft in the South China Sea would invoke US mutual defense commitments.”

21 November 2022, 18:38 GMT

It remains to be seen whether the Philippines will let itself be sucked into the Pentagon’s "first line of defense" strategy of containing China. The benefits of such a relationship to Washington are clear – giving it a proxy with which to pick a fight with its most significant global adversary without any risk to the American homeland. What Manila gets out of the relationship is far less certain.