The Russian army says Larisa Romashkina's son hanged himself with a dog leash three months after he was conscripted, but she cannot believe the 22-year-old would have committed suicide.

"There should be some strong reason for a suicide," Romashkina says, her light-blue eyes filling with tears. "But there were no reasons. The only reason was the army."

It was in late March when she received a call from an officer of the army unit in the Moscow Region where her son Alexei Bulanov was serving.

"It was a Tuesday, around 3 p.m.," she recalls, fiddling nervously with her fingers. "They told me that he had hanged himself."

Investigators say they are considering two possible explanations for Bulanov's suicide: that he had recently learned he was HIV-positive and was having family problems. Before killing himself, they say he told a fellow conscript in Lukhovitsy that neither his mother nor his grandmother needed him, supposedly following an argument with his family.

Romashkina dismisses their theories.

Before Bulanov left his military base for a short vacation, his commander ordered him to bring 15 liters of white paint and 5 packs of Xerox paper, she says. It was the second time since Bulanov joined the army in December he'd been told to bring paint and paper back from home leave - another time the demand was for two bottles of vodka.

"But this time, he was returning empty-handed. I regret not calling his base commander," she says, staring into space. "When Alexei was leaving the base, his platoon commander told him: 'When you come back, I will crush you.'"

Unwritten dead

As Russia prepares to celebrate its armed forces' victory in World War II, there is a darker side to today's army. It has always been notorious for hazing, but extortion has become widespread only in the past few years, says Veronika Marchenko, who heads the Moscow-based Mother's Right foundation, a nongovernmental organization helping families whose sons died during their military service.

Last year, the foundation provided legal support to more than 4,270 families with sons who died while serving in the army. Most cases date back to the Chechen wars of the mid-1990s and early 2000s.

Many are new cases, however, and Bulanov's case is "very typical," she says. There were problems in the army in Soviet times, "but there was no extortion in such a commercial sense, when someone can die because of 3 rubles. Conscripts are now seen as a source of income."

The decade-long debate on the number of professional servicemen in Russia's armed forces is unresolved, and they still largely rely on conscription. All Russian men between the ages of 18 and 27 are obliged by law to perform one year of military service.

"Several thousand young men perish in the army every year," Marchenko says. According to the Russian military authorities, the figure is much lower - Prosecutor General Yury Chaika reported in late April that 478 soldiers died in Russia last year in non-combat situations, 14 percent less than in 2009.

Marchenko says the discrepancy arises because many deaths are not included in the official figures. "How can a mother bury her son and visit his grave every day, but this is not recorded anywhere?" she asks, complaining that it is more than two years since statistics on soldiers' deaths have been published on the ministry's official website.

Preventable deaths

The Mother's Right foundation says that of the families who turned to them for help in 2010, only 2 percent had sons who died in combat. Most of the deaths were due to accidents (33 percent), suicides (28 percent) and illness (21 percent). "Acts of harassment," including beatings, accounted for 7 percent.

"Most of these deaths could have been prevented - and the state should have prevented them," Marchenko says.

Only about 10 percent of the suicide cases raise no question, she says, while another 10 percent are forcible suicides, which soldiers commit as a result of repeated humiliation or threats. The rest, Marchenko says, are simply murders masked as suicides.

Moving from conscription to a professional army would improve the situation, observers say, but that is a long way off. According to expert estimates, only about 25 percent of Russia's roughly 1 million military personnel are contract servicemen.

Military authorities have admitted that the situation should be changed. Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov announced in mid-March that the number of contract personnel will be raised to 425,000, while Chief of the General Staff Army General Nikolai Makarov said later in the month that Russian military authorities were aiming to decrease the proportion of conscripts to 10 or 15 percent.

Investigation ongoing

Reports of hazing and harsh conditions mean many young men go to great lengths to avoid conscription, including by bribing military officials and doctors for medical exemption certificates.

Romashkina says her son wanted to join the army, but she stopped him going for four years, even throwing away his draft letters.

"I was always afraid. Now I feel that I gave them my son - and he just disappeared," she says, looking away as she holds back her tears.

The investigation into Bulanov's death, which was to be concluded in late April, has been extended, and Romashkina says she does not know how it is going. She says she sent a letter to President Dmitry Medvedev about two weeks ago asking for help.

She is still waiting for a reply, and says she doubts that the truth about her son's death will ever be revealed.

Investigators and local military authorities say there is nothing to "reveal" and the mother should accept that it was either their quarreling or his disease that drove him to kill himself in a shed at the military base.

The Ryazan Garrison military prosecutor says he cannot comment on an ongoing investigation. A father of three children, Yury Trubnikov says he understands a mother's grief, but complains that media reports casting doubts on the official version of Bulanov's death are one-sided and incorrect.

The prosecutor of the Podolsk Garrison, which has taken charge of the investigation from the Ryazan Garrison, was not available for comment.

'I should have sent him to prison'

Six weeks after answering the phone on that Tuesday afternoon, Romashkina says she still cannot believe her son is dead. "When I go to the cemetery, I can't convince myself that it's him who is lying there in that grave."

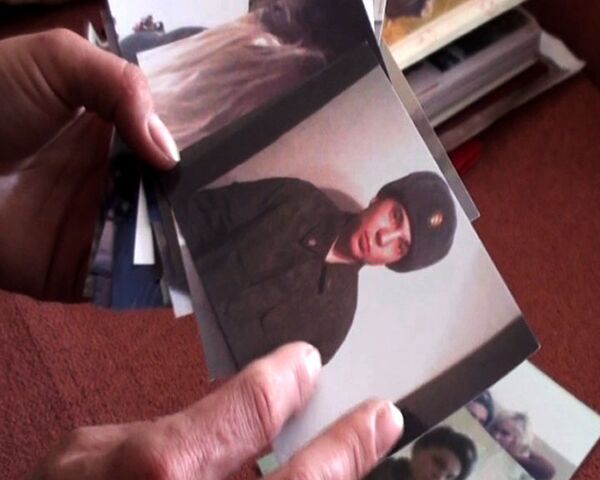

She plays a video on her mobile phone, shot several days after her son joined the army.

In it, Bulanov puts on his new military uniform, then jumps to attention with exaggerated zeal, making his visiting mother and girlfriend laugh. He makes several attempts to put his military hat on by throwing it onto his head, and then puts it on his girlfriend's head and hugs her.

"I don't know how to continue living," Romashkina says, the tears now rolling down her cheeks. "I should have sent him to a prison. He would have been much safer."

RYAZAN, May 5 (RIA Novosti, Maria Kuchma)