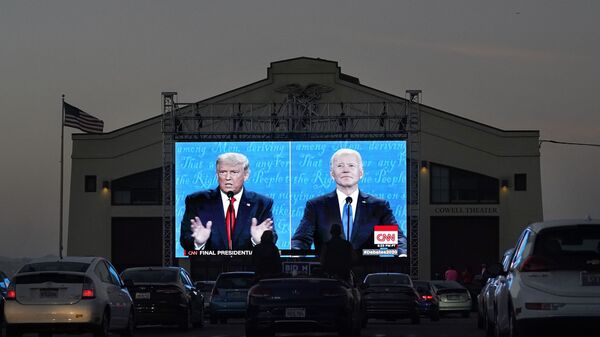

As the vote counting continues in the US elections, President Donald Trump, to date, has succeeded in garnering 214 electoral college votes, trailing behind his Democratic opponent Joe Bide, who has amassed 264 votes out of the 270 required to claim victory.

Amid the continued vote tabulation, Donald Trump, who has so far defied pollsters' predictions of a Biden landslide, said at the White House: “We were getting ready to win this election… Frankly, we did win this election." Trump added that the current outcome was “a major fraud on our nation".

Democrat Joe Biden voiced optimism that he would win enough states to become president. In remarks from the Chase Center in Wilmington, Delaware, he said: “When the count is finished we believe we will be the winners.”

The tight electoral race and the statements made by the two contenders for the White House have led election experts to take a closer look at the possible legal scenarios that might unfold if election results were to be disputed.

How's the Outcome Decided?

The outcome of US presidential elections is decided by a two-step system, where votes in a state are followed by a second vote by the Electoral College on 14 December.

With each US state allotted a number of "electors" based on its population, it is down to them to cast a ballot for the certified winner of the popular vote in each state.

A candidate must collect 270 votes out of a total of 538 to claim victory, with votes formally counted at a joint session of the House and Senate on 6 January.

In a textbook example of how it works, Donald Trump could win reelection with a minority of the popular vote by winning in the Electoral College, as was the case in his standoff with Democrat Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Back then, he lost the national popular vote to Clinton but secured 304 electoral votes to her 227.

Electoral College Act

8 December is what is termed a "safe harbour" date, with states expected to submit certified slates of electors to the Archivist of the United States by then.

However in the eventuality that continuing tabulation of votes or legal battles have prevented a state from doing so, there is a federal law provision that allows the aforementioned state's legislature to convene and appoint a slate of electors ahead of the final vote tally.

The controversy here is that a partisan legislature could potentially appoint a slate of electors that support the candidate who ultimately loses the state's popular vote.

If the governor and the legislature are split between parties in a specific state, with the governor officially certifying the slate of electors, a state might submit two slates of electors.

Battleground states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and North Carolina all have Democratic governors and Republican-controlled legislatures.

Faced with rival slates of electors from the same state, the House and Senate vote to determine which will be accepted. The slate of electors is counted if they concur, and the slate certified by the governor prevails in a case where the House and Senate disagree, according to the Electoral College Act.

Many scholars interpret the act, which states that the electors approved by each state’s “executive” should prevail, as signifying that a state’s governor should predominate. However, others dismiss that argument.

As of now, Republicans hold the Senate while Democrats control the House of Representatives, but the electoral count is conducted by the new Congress, which will be sworn in on 3 January.

Another scenario is that Trump’s Vice President Mike Pence, as Senate president, may attempt to throw out a state’s disputed electoral votes if the two chambers cannot agree.

In that case, the Act does not specify if a candidate would still require 270 votes, a majority of the total, or might win with a majority of the remaining electoral votes.

Both parties could potentially ask the Supreme Court to resolve a congressional stalemate.

‘Contingent Election’ or What Happens in a Tie?

Even after the electoral vote has been counted, there is a potential scenario when there could be no winner of the presidency.

If neither candidate has secured a majority of the electoral vote, or both candidates finish with 269 votes, this triggers a “contingent election” under the 12th Amendment to the Constitution. It then falls to the House of Representatives to decide who wins the election, while the Senate selects the vice president.

Each state delegation in the House receives a single vote.

To date, Republicans control 26 of the 50 state delegations, while Democrats have 22; one is split evenly and another has seven Democrats, six Republicans and a Libertarian.

An election dispute in Congress need to be settled by the strict deadline of 20 January, when the Constitution mandates that the term of the current president ends.

If Congress fails to declare a presidential or vice presidential winner by then, under the Presidential Succession Act, the Speaker of the House, currently California Democrat Nancy Pelosi, would serve as acting president.

In Case Trump Loses, Will He 'Bury' Biden in Lawsuits?

Congress would typically certify the results of the Electoral College two weeks before Inauguration Day. However, as Donald Trump and his campaign issue legal challenges contesting the vote tally, and should Trump opt to stay in the White House until the court battle is resolved, the resulting delay in Congress producing a decision might take events into “uncharted territory" beyond the Constitutionally-set 20 January transfer-of-power date.

As Biden is outpacing Trump in the quest to win the White House, the incumbent president has already signaled that he and his campaign are ready to have the 2020 election settled in the Supreme Court.

If a Trump lawsuit reached the Supreme Court, which currently has three POTUS-appointed justices, it might potentially make a legitimate decision that would hand over victory to Donald Trump.

In one of the most contentious election litigation cases, the 2000 presidential race between Democrat candidate Al Gore and his Republican challenger George W Bush led to weeks of messy recounts in Florida after Election Day.

As the recounts, requested by Gore, continued for three weeks, Florida’s then-Republican secretary of state certified a win for Bush by 537 votes, thus giving him the state's 25 electoral votes, which pushed him past the Electoral College threshold to win the presidency.

Gore, however, filed a lawsuit in Florida to request that the state keep recounting the votes, which, in turn, prompted the Florida Supreme Court to order Florida to recount thousands of ballots manually that the counting machines had not registered.

Bush later turned to the US Supreme Court to reverse the state court’s ruling and stop the recount. Thanks to the Supreme Court’s five conservative justices, Bush's request was granted. His Democrat rival eventually conceded the election and accepted the Supreme Court's decision.