Earlier this month, Sweden stunned the world by claiming the Viking heritage could have been possibly influenced by Islam, brandishing a Viking-era burial cloth which was claimed to feature words like 'Allah' in geometric Kufic script.

After giving some of the findings a fresh glance, archaeologist Annika Larsson of Uppsala University claimed some of the silk patterns, originally thought to be traditional Viking Age-decoration, to display Islamic script. As the patterns were found in separate grave sites, the Swedish academia jumped at the idea that Viking funeral customs had been influenced by Islam, a notion that was gladly picked up by the leading Swedish media, including newspapers Aftonbladet and Uppsala Nya Tidning, as well as Swedish Radio, all of which are generally supportive of multiculturalism.

In a series of refuting tweets, Mulder explained that the geometric style called square Kufic was indeed common and Iran and Central Asia, yet only after the 15th century, whereas the Viking age effectively ended in the mid-11th century.

Assuming that Kufic script did exist (which it apparently did not), the inscription still did not mean anything in Arabic, she contended, as the inscription simply didn't spell "Allah." "Instead, the drawing said للله ‘lllah', which basically makes no sense in Arabic," Professor Mulder explained.

There is a small triangular shape, but no final ha ـه. Frag. was published in 1938 by Agnes Geijer, original drawing looked like this: 31/60 pic.twitter.com/DxDossuWzs

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

Lastly, Professor Mulder claimed the evidence of Islamic influence presented by Larsson to be based on "conjecture" and "supposition" rather than "proof."

But reconstruction drawing by @UU_University textile archaeologist Annika Larsson shows extensions on either side that include a ha. 32/60 pic.twitter.com/1NyQzcqDV2

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

Nevertheless, Annika Larsson decided to stick to her guns.

"Even so, the characters should be interpreted as 'Illah,' it is still Kufic, and as I have understood from the Arabic experts it still refers to 'Allah,'" Larsson told the Independent.

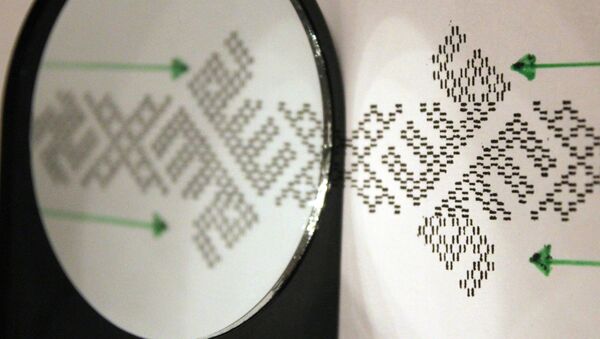

The Swedish website Allmogen stated Annika Larsson added parts of the pattern and furthermore mirrored it to make the Arabic god's name appear among the symbols.

"One used their imagination and simply fantasized. And this little detail was omitted from the press release," Daniel Sjöberg of Allmogen concluded, citing Viking textile specialist Carolyn Priest-Dorman who claimed the text was based on "extensions of pattern," rather than existing pattern.

Larsson admitted that the image was a "visualization of the puzzle" intended only to raise questions that can provoke new discoveries and perspectives.

Incidentally, the very same cloth that served as the inspiration for Uppsala University's groundbreaking conclusion, contained several swastikas — ancient religious symbol commonly used in the Iron Age and onwards.

"How did the 'experts' miss the fact that the Vikings were actually Islamic Nazis?," a Twitter user wrote wryly.

To your overall points: look at the swastikas. How did the "experts" miss the fact that the Vikings were actually Islamic Nazis? /s pic.twitter.com/OPKvaAU2mA

— WonderBoyWonderings (@WonderBoyWins) October 17, 2017

During the Viking Age, which spanned from the late 8th century to the mid-11th century, the Scandinavians explored swaths of Europe and Asia for trade and conquest, establishing outposts from today's Greenland to Russia, Ukraine and Turkey.

Modern Swedes' ancestors are known to have utilized the Volga Trade Route and the Trade Route from Varangians to the Greek to enable interaction between cultures and extensive trade. At Sweden's Birka and Helgö, both prominent centers of Viking culture, previously unearthed grave goods included a Buddha from India and a Coptic ladle from North Africa.

At #Birka and earlier, at nearby #Helgö, #Viking grave goods included a Buddha from India and a Coptic ladle from North Africa 46/60 pic.twitter.com/o805RUlKCr

— Stephennie Mulder (@stephenniem) October 16, 2017

#Byzantine art: #Varangian Guards (in ceremonial costumes). Nea Moni-Chios Monastery-1040's. pic.twitter.com/Mf94W47eFr

— Hagia Sophia (@hagiasophiatr) December 7, 2016

Until the late 11th century, the Byzantine capital of Constantinople was known as home to the elite Varangian Guard, most members of which were Scandinavians or early Russians. Constantinople itself, which had a considerable diaspora of Norsemen, was also known as Miklagarðr ("Great City"). Written evidence suggests that Vikings made it as far as Baghdad. The same Birka boat grave that hosted the "Allah" shroud also featured Arabic coins used only in Baghdad.

A very long way from home: early Byzantine finds at the far ends of the world — new post by me:) https://t.co/T77LIhSD2g pic.twitter.com/jW7Mtvv3Pi

— Dr Caitlin Green (@caitlinrgreen) March 21, 2017