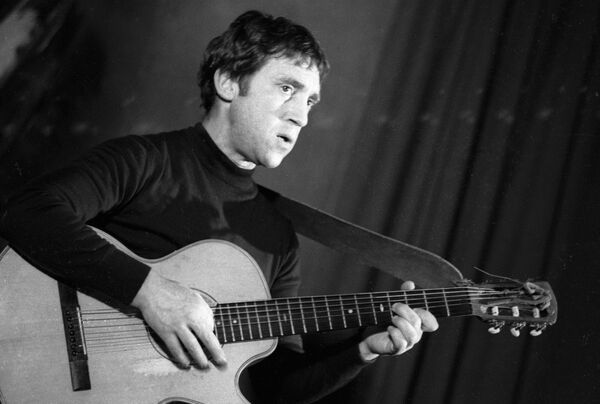

Iconic Soviet singer, songwriter, poet, and actor Vladimir Vysotsky (1938-1980), whose career had an immense and enduring effect on Russian culture, died exactly 30 years ago.

Three days after his death, a short-lived civil society was born in the Soviet Union's capital. Thousands of people came to pay their last respects to Vysotsky at the Taganka Theater, and they didn't do it on orders from an organizing committee, but completely of their own free will.

This spontaneous display of love and affection for Vysotsky caught the Soviet government completely by surprise. All the Kremlin could do in that pre-glasnost era was to pretend that nothing had happened.

Vysotsky's death was not typical of the Soviet totalitarian era. But had his life been equally unusual and extraordinary? The answer is probably "yes" if we consider his vast talents, but that has nothing to do with historical epochs and political systems. Geniuses come into this world by sheer chance.

An objective assessment of Vysotsky's literary heritage shows that it cannot be called purely pro-Soviet or anti-Soviet; it simply does not fit these parameters.

Although drawing comparisons is an unrewarding task, two other poets, Alexander Galich and Bulat Okudzhava, wrote their songs and verses at the same time as Vysotsky and in the same style. Both men also performed their poetry to guitar music.

Their fates were quite different. Galich chose an open opposition to the Soviet regime until his public performances were banned and he was forced to emigrate. Okudzhava, however, gave concerts and behaved like a quiet dissident, hinting at certain "esthetic disagreements" with the authorities. But he did not openly oppose the government.

Vysotsky was by no means a Galich-style dissident poet and tried to avoid making any kinds of political statements. At the same time, he did not poetize "the commissars in dusty helmets" like Okudzhava, who had joined the Soviet Communist Party after the history-making 20th Congress which denounced Josef Stalin's personality cult in 1956. Nor did he have any illusions about "socialism with a human face" harbored by the Shestidesyatniki movement, which involved progressive Soviet intellectuals, writers and academics in the 1960s.

None of his songs, novels, verses and poems pays tribute to Vladimir Lenin, the Communist Party or the Young Communist League (Komsomol), the three pillars of post-Stalin Soviet ideology. It seemed that this triad simply did not exist, as far as Vysotsky was concerned.

Vysotsky wrote about everyday life in the GULAG prison-camp system, overlooking its political aspects. Objectively speaking, Vysotsky's creative output highlighted a social protest. Although he never openly denounced the Soviet regime, Vysotsky behaved like a typical poet who should expose universal human evils and vices.

This concept of the poet and poetry has not become obsolete today. Real poetry never goes out of fashion. It is always relevant, not on the level of slogans or public pathos but in its real essence because it takes centuries, not decades, to change human nature.

The same is true of Vysotsky's satirical songs, which could be perceived as an invective against Soviet censors. But this rather strange viewpoint is worthy of characters from his songs. Vysotsky himself would have been unpleasantly surprised by such an interpretation of his songs.

We know nothing about Vysotsky's attitude toward the Soviet system and whether he stood out in this respect among other Soviet intellectuals. One gets the impression that Vysotsky did not consider this to be a worthy subject for his work, not for fear of the government but because he was above it.

To quote a recent encyclopedic entry on Vysotsky, he touched upon an entire range of banned subjects during the years of strict censorship and was largely banned as a result. "Despite existing restrictions, Vysotsky's popularity was and remains phenomenal. This is due to his charming and outstanding personality, poetic gift, his unique prowess as a performer, extreme sincerity, love of freedom, the vibrant energy of his songs, roles and parts, as well as to his masterful execution of subject matter and the realism of his images," the entry goes on to say.

Although it is hard to disagree with the second part, the first two sentences combine myth and reality. In some cases, the poet touched upon various censored themes, including the immigration of Jews to Israel or a stupid briefing before Soviet people's trip abroad. But these unimportant details did not undermine the foundations of the Soviet system. The ideological agencies always discerned between what was acceptable for the press and TV programs, and what could only be performed at unofficial concerts.

In fact, Vysotsky was never banned and did not hide in the artistic underground. True, he was not allowed to perform on radio or TV, and to join the Soviet Writers' Union. None of his poems was published in Vysotsky's lifetime, to say nothing of publishing an entire book. Nonetheless, some of his records were released. Although Vysotsky had regular run-ins with Culture Ministry officials, he received a top professional qualification category of a crooner and guitar performer two years before his death.

Vysotsky's relationship with cultural and literary agencies could not have been easy and cloudless because he was a phenomenon that did not fit inside the Soviet-era administrative and bureaucratic system. Although Vysotsky was not its enemy, he existed outside and independently of that system. He remained free and therefore unregimented. This always scares the officials of any rigidly regimented state, including the Soviet Union.

At the same time, such authors and singers always win popular acclaim. Vysotsky's unregimented self-expression, which was not affected by censorship, only boosted his phenomenal popularity. People realized that his songs were free of hypocrisy and deception, and that he spoke the truth about the Soviet period, himself and his contemporaries.

However, it was impossible to hear such artistically expressed truth anywhere else. So we have to admit that, although such poets can emerge anytime, the phenomenon of Vladimir Vysotsky could only have evolved in a walled-in society and in a totalitarian system. However, this phenomenon was made possible only during the Brezhnev-era stagnation, also referred to as "developed socialism," but was unthinkable in Stalin's times when people like Vysotsky were either killed or carted off to prison camps.

The Soviet era is long gone, but Vysotsky continues to live among us. It is a well-known truth that an artist who has expressed and reflected his times to the greatest possible extent stays alive for a long time and perhaps forever.

But what a performance Vysotsky could have given today!

(RIA Novosti political commentator Nikolai Troitsky)

The opinions expressed in this article are the author's and do not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.