In the 1840s and the 1850s, two intellectual movements, namely, the Slavophiles and the Westernizers, emerged in Russian society and philosophical thought. The Slavophiles advocated Russia’s unique way of development, whereas the Westernizers insisted on the need to follow in the wake of Western civilization and imitate the Western socio-political system, civil society and culture.

Poet Konstantin Batyushkov was the first to use the word “Slavophile” in the ironic sense to denote a certain archetype. The term “Westernization” was coined in Russian culture in the 1840s and was mentioned in the memoirs of writer, literary critic and journalist Ivan Panayev. The term came to be frequently used after a split between critic and writer Konstantin Aksakov and critic Vissarion Belinsky in 1840.

Archimandrite Gavriil (Vasily Voskresensky), who co-founded the Slavophile movement, published his book Russian Philosophy in Kazan in 1840. The book made it possible to assess the emerging movement.

The Slavophiles developed their views in ideological disputes, which became aggravated after the publication of Philosophical Letters by Russian philosopher Pyotr Chaadayev. The Slavophiles offered substantiation for Russia’s unique way of historical development that was completely different from the Western European model. They believed that Russia’s unique feature was highlighted by the absence of a class struggle in its history, by peasant communes and artels (cooperative associations of peasants and workers), as well as by Orthodoxy, the only true form of Christianity.

Writers, poets and academics Alexei Khomyakov, Ivan Kireyevsky, Konstantin Aksakov and Yury Samarin played the lead in elaborating the Slavophile doctrine. Other notable Slavophiles included Alexander Koshelev, Dmitry Valuyev, Fyodor Chizhov, Ivan Belyayev, Alexander Gilferding, Vladimir Lamansky and Vladimir Cherkassky. Writers Vladimir Dahl, Alexander Ostrovsky, Apollon Grigoryev, Fyodor Tyutchev and Nikolai Yazykov supported socio-ideological aspects of the Slavophile doctrine. Historians and linguists Fyodor Buslayev, Osip Bodyansky and Dmitry Grigorovich also were supportive of the Slavophile concepts.

Moscow was the focus of the Slavophile movement in the 1840s. The Slavophiles mostly gathered at the Yelagin, Sverbeyev and Pavlov literary salons, debating with the Westernizers there. Slavophile works were heavily censored, and some members of the movement were placed under police surveillance and even arrested. Due to censorship, the Slavophiles did not have their own permanent publications for a long time and mostly published their works in the Moskvityanin magazine. After censorship was somewhat mitigated in the late 1850s, they started publishing the Russkaya Beseda (Russian Conversation) and Selskoye Blagoustroistvo (Rural Improvement) magazines and the Molva (Common Talk) and Parus (Sail) newspapers.

On the subject of Russia’s historical development, the Slavophiles disagreed with the Westernizers, opposing the adoption of Western European political models. At the same time, they emphasized the importance of trade and industry, the establishment of new shareholding companies and banks, railroad construction and the use of farming machinery. The Slavophiles advocated the abolition of serfdom from above and the allocation of land to peasants.

Khomyakov, Kireyevsky and Samarin, the main Slavophile philosophers, created their own philosophical doctrine. The Slavophiles believed that the true East Orthodox faith borrowed by Rus predetermined the Russian nation’s special historical mission. East Orthodoxy was marked by Sobornost, the term for organic unity and integration and the salient feature of Russian society’s life. The innermost foundations of the Russian soul were formed by Orthodoxy and traditional peasant communes.

The Slavophiles idealized the Russian nation’s patriarchal nature and the principles of traditionalism and perceived it in the spirit of conservative romanticism. At the same time, they called on intellectuals to merge with the people and to study their way of life, culture and language.

Slavophile concepts were reflected in the philosophical doctrines advanced by Vladimir Solovyov, Nikolai Berdyayev, Sergei Bulgakov, Lev Karsavin and Pavel Florensky in the late 19th century and the early 20th century.

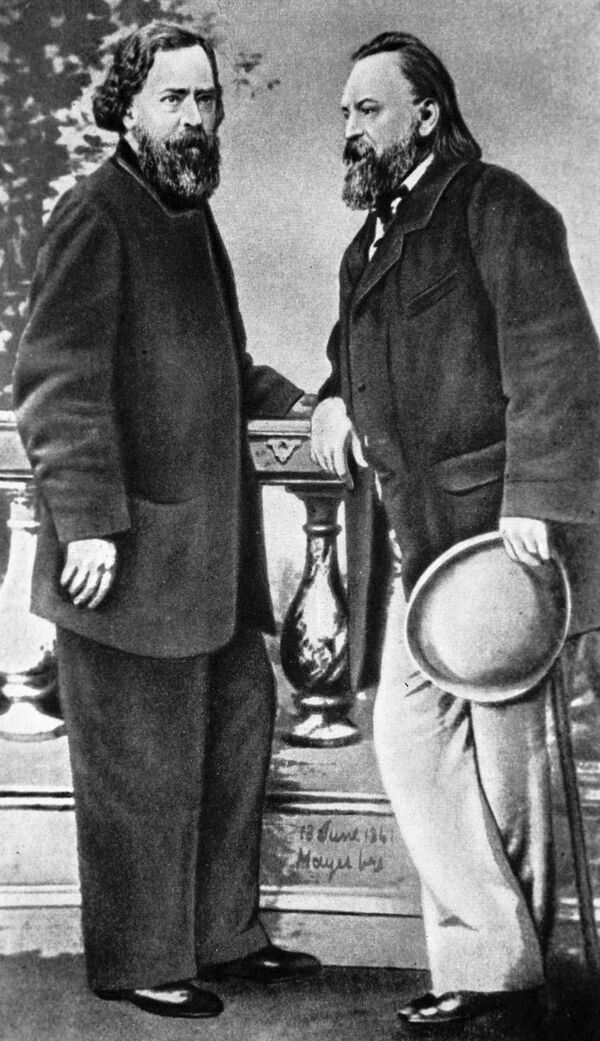

The Westernizers were a group of 19th century Russian intellectuals who opposed feudalism and the Slavophiles in the 1840s. Writer Alexander Herzen described their ideological disputes, held at Moscow’s literary salons, in his book My Past and Thoughts. Alexander Herzen, Timofei Granovsky, Nikolai Ogaryov, Vasily Botkin, Nikolai Ketcher, Yevgeny Korsh, Konstantin Kavelin and some others comprised the Moscow Westernizers group. Belinsky, who lived in St. Petersburg, maintained close ties with the group.

Writer Ivan Turgenev was also a Westernizer. Representatives of the movement rejected feudalism and serfdom in the economy, political life and culture, and demanded Western-style socio-economic reforms. The Westernizers deemed it possible to establish a bourgeois democratic system by peaceful means. They believed that education and propaganda could forge Russian public opinion and force the Tsar to launch bourgeois reforms. Also, they had a high opinion of Peter the Great’s reforms.

The Westernizers called for overcoming Russia’s socio-economic backwardness on the basis of progressive European experience, rather than promoting unique elements of national culture. They prioritized the common aspects of Russian-Western historical and cultural destinies, rather than mutual disagreements.

In the mid-1840s, the Westernizers movement split into the liberal and revolutionary democratic wings after a major dispute between Herzen and historian Timofei Granovsky. The liberal wing comprised Annenkov, Granovsky, Kavelin and some others, whereas the revolutionary democratic wing consisted of Herzen, Ogaryov and Belinsky. The two groups disagreed on attitudes toward religion. Granovsky and Korsh advocated the immortality of the soul, while the democrats and Botkin preached atheism and materialism. The two groups also debated specific reform methods and Russia’s post-reform development. The democrats advocated revolutionary struggle and the construction of socialism. These disagreements were also reflected in the esthetic and philosophical spheres.

The philosophy of the early Westernizers was influenced by Johann von Schiller, Georg Hegel and Friedrich Schelling, and later by Ludwig von Feuerbach, Auguste Comte and Henri de Saint Simon.

The Westernizers ceased to exist as a unique aspect of Russian public thought after the reforms of Alexander II, which promoted capitalist development.

The Westernizers’ views were expounded by Russian liberal thinkers of the late 19th century and the early 20th century.