With Moscow tottering on the doorstep of a new "post-Luzhkov" era, the public image of the ex-mayor's favorite artist, Zurab Tsereteli, is rapidly going down the drain.

Mind you, it was never more than a solemn infamy.

Tsereteli, a Georgian-born monumentalist sculptor, has always been something of a Mauvais ton among Muscovites - not even half as bad as taking delight in the cinematographic credentials of the Kremlin's favorite director, Nikita Mikhalkov.

Luzhkov, who - disastrously - fancied himself as an arts buff, commissioned loads from Tsereteli, and a big load of problems he got back. Almost every Tsereteli creation throughout the 1990s and the early 2000s was met with groans and baffled faces.

There's the glass-and-bronze ensemble of Manezh Square outside the Kremlin; there's the Eternal Friendship pillar between the Russian and Georgian peoples on Tishinskaya Square (more generally known as the "kebab"); there's finally his 98-meter colossus on bronze legs - the much-mocked monument to Peter the Great on the Moscow River.

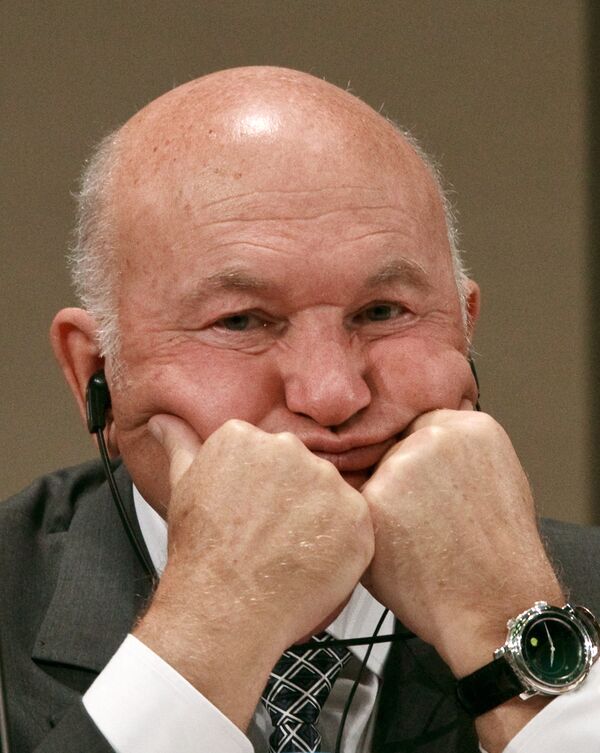

"I may not know much about art but I know what I like" - this tired cliche may well be the perfect tagline for Yury Luzhkov's 18-year-old rule over the Russian capital. It would be funny were it not so tragic, one might say.

"The architectural image of the new Moscow has become... a reflection of its heroic myth," writes Konstantin Mikhailov, an architecture activist, in an article in the Ogonyok magazine.

The thrust of this myth is simple enough: "The Moscow of the pre-Luzhkov epoch was a dirty, inconvenient, and unsettled city of the late Sovok [a derogatory term for the USSR]... Now it is a modern European megapolis with glittering shop windows, skyscrapers, highways, underground parking facilities, bowling centers and aqua parks," Mikhailov says.

Hundreds of historic buildings and entire neighborhoods fell prey to this myth. Luzhkov replaced them with their replicas - or more often with shopping malls and high-class housing for Russia's elite.

"In Moscow's culture, the concept of the replica has sometimes no less significance than that of the original," Luzhkov wrote back in 2004 in his article in the Izvestiya magazine.

This baleful desire to outdo history, to replicate history, or more to the point, to control history, to make the past suck up to the present, is part of Luzhkov's great Moscow myth.

But in the process of rebuilding the past, Luzhkov and Moscow's genius loci, Tsereteli, were perhaps too engulfed in their myth to notice how the myth itself had gained the upper hand, how it had come to control them.

Hence the gigantomania, the grotesqueness of much of Tsereteli's work. The 98-meter tall monument to Peter the Great, now at the center of a controversy over Luzhkov's legacy, is taller than the Statue of Liberty (93 meters tall). Why so big? The sky is the limit. This "gigantomania" is in turn a reflection of a sort of Stalinesque hardline one-sidedness of much of contemporary Russian politics.

But Peter, for one, may soon leave the stage. For the past two weeks now, Russian cities have been lining up for Moscow's monument to the first Russian emperor after acting mayor Vladimir Resin said it may be removed.

It may be a sign of change, and then again it may not be, but those in charge of the new Moscow are looking to rid it of the most conspicuous marks of Luzhkov's rule. But whether they themselves will fall into the trap of rebuilding the past while not quite being able to grasp the present, we are yet to discover.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author's and do not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

MOSCOW, October 11 (RIA Novosti, by Alexei Korolyov)