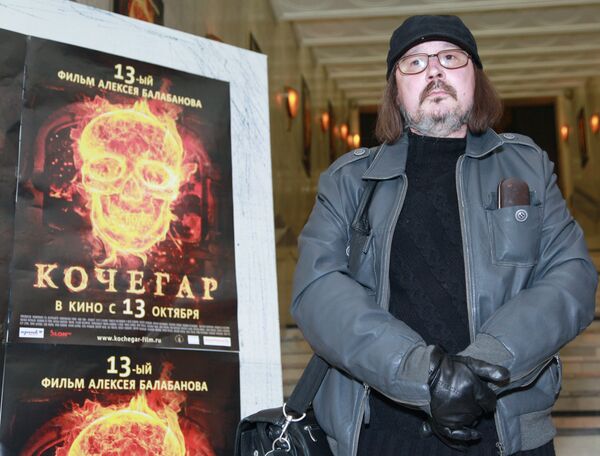

A worrying flashback to the 'wild 90s,' a poignant tale of loyalty and betrayal, Alexei Balabanov's new film, the Stoker, raises the curtain on a Russia most would prefer not to know.

Kochegar (The Stoker) is set in a crumbling industrial town in Russia's gloomy north, the kind of town Russia's rulers will not be boasting about in the run-up to the 2012 presidential elections.

It's bleak, it's wintry, and it's unremittingly hopeless. Ivan Skryabin, an ethnic Yakut (a people of northeastern Siberia), who was concussed during the infamous war in Afghanistan, is a stoker at a boiler house. His former fellow-in-arms, now a local criminal crook, burns the corpses of his ex-foes in the boiler, but it's okay, he tells Skryabin, they were bad people anyway.

But when he burns Skryabin's daughter in it for sleeping with his own daughter's lover, the somewhat cranky Yakut begins to see things more clearly.

The war still rages on, he concludes. Only back then it was us against them, and now it's - inexplicably - us against us. With something amounting to almost regal dignity, he takes his revenge and then his life.

The Stoker would be little more than a lurid tableaux of contemporary Russia were it not for Balabanov's brutal realism (perhaps a tad exaggerated, but then again, you have to get your point home somehow, don't you?), which will strike an unsettling chord with Russia's growing middle class, mollified by their recent rise in prosperity.

"Don't give us this blood, this cruelty!" they seem to moan. "We've had enough of it already, in Chechnya, in Beslan. Give us the real stuff!" Why, if you want to see the real stuff, this is it, Balabanov says. Constrained opportunity, organized crime, industrial bleakness - this is the real stuff; if you would only look.

By refusing to play along with Russia's renewed efforts to reassert itself as a superpower, Balabanov is without a doubt swimming against the tide. His best-known films, including the 1997 bracingly brutal gangster thriller, Brother; the 1998 wondrously perverse Of Freaks and Men; and the 2002 shockingly violent War, set in war-torn Chechnya, have often been attacked by mainstream filmmakers.

The Kremlin's favorite filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov claimed Brother's hero Danila was "imbued with destruction," threatening the spiritual welfare of the nation's youth. And somehow I suspect the veteran director will not enjoy Balabanov's new film either.

The Stoker is a film of poignant flavor, perhaps not to all tastes; but for a glimpse of the real Russia, it must be seen.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author's and do not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

MOSCOW, October 19 (RIA Novosti, Alexei Korolyov)