The Mikheil Saakashvili administration has touted its recent abolition of visa requirements for citizens of Russia’s North Caucasus republics as a step to facilitate tourism, trade and educational relations. Moscow, meanwhile, dismisses this unilateral move as a mere “provocation,” and is clearly irritated by Tbilisi’s appeal to its troubled southern flank. As president Saakashvili promotes the idea of a “united and peaceful Caucasus” on the international stage, it seems that his intentions may be just the opposite.

Is Saakashivli’s Move to Abolish Georgian Visas for the Citizens of Certain Russian Republics a Way to Provoke Moscow to Take Heedless Action?

TBILISI, Georgia/The presidential decree that came into force on October 13 abolished the entry visa requirement for citizens of the Dagestan, Chechnya, Ingushetia, North Ossetia, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachayevo-Cherkessia and Adygeya republics of the Russian North Caucasus. Citizens of these regions should now be able to cross into Georgia without a visa for up to 90 days via the Upper Lars border crossing point in the mountainous Kazbegi Region, which was re-opened after four years’ closure in March this year. The explicit visa regime cancellation notably excludes citizens of the majority ethnic Russian Krasnodar Region, however, despite the fact that it borders Georgia to the north. President Saakashvili’s spokesperson, Manana Manjgaladze, explained that the visa-free regime is a follow-up to Saakashvili’s UN General Assembly speech a month ago, in which he outlined his vision of a “united and peaceful Caucasus.”

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov was quick to dismiss the move as a “propaganda” stunt, and criticized the Georgian administration’s unilateral decision as a departure from the standards of “civilized” international interaction. Grigol Vashadze, his Georgian counterpart, meanwhile asserted his own country’s sovereign right to determine its own visa requirements, rejecting any obligations for bilateral agreement on such issues in light of Russia’s “occupation” of breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Moscow’s recognition of the sovereignty of these republics and the ongoing Russian presence there following the “five-day war” over South Ossetia in August of 2008 remains the intractable bone of contention between Georgia and its larger neighbour.

But Russia-Georgia visa issues have a history of being exploited for ends beyond mere technical questions of border control. It was Moscow, after all, that unilaterally imposed the first visa obligation between the two post-Soviet states back in 2000, when Georgia was still a member of the Russian-led Commonwealth of Independent States. Back then the visa regime – halting the flow of migrant workers into Russia and thereby slashing remittances important to the frail Georgian economy – was the Kremlin’s punishment of Tbilisi for its persistent failure to deal with separatist militants taking refuge on the Georgian side of the mountains.

Archil Gegishidze, a senior fellow at the Tbilisi-based Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies, views the Saakashvili administration’s move as “a kind of reciprocity” for that visa regime initiated a decade ago, which put additional symbolic pressure on Tbilisi by exempting de-facto independent Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The latest Georgian move, though within the bounds of international law, similarly addresses citizens of the Russian Federation’s North Caucasus republics directly, independently of central government. In light of Moscow’s sensitivity to developments in a region that has been torn up by separatist violence and the attempts to contain it for the past two decades, this might indeed be seen as a “provocation.”

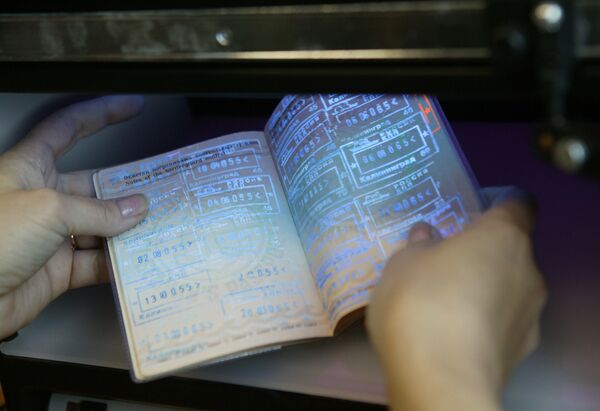

On a practical level, the visa-free regime makes sense for North Caucasus residents wishing to enter Georgia over land, because in the absence of diplomatic relations between Tbilisi and Moscow they have had to visit the “Russian Interest Section” of Georgia at the Swiss embassy in Moscow to obtain the visa. However, the application of the visa-free regime in practice – in the form advertized at least – faces certain limitations. Firstly, the Russian Federation passports used by citizens crossing the state borders do not specify a place of residence, making it impossible to restrict visa-free travel to residents of the autonomous North Caucasus republics alone. Equally, any visa-free entry into Georgia will be subject to approval by border guards on the Russian side, which will not be forthcoming without Moscow’s consent.

Tbilisi’s official rationale for the decision has been voiced in two distinct strands: the first centers on the aim of enhancing tourism, trade and educational links between the South Caucasus country and its northern neighbours, while the second is the idea of showcasing Georgia as a model of democratic and modernizing reforms. Gegeshidze, however, believes that for the next couple of years tourism and trade benefits to Georgia from links with the North Caucasus republics will likely be negligible.

Tbilisi’s second justification seems closely connected with president Saakashvili’s plans for a united and peaceful Caucasus in the particular sense of establishing Georgia as a center of gravitation in the region. Gegishidze does not foresee imminent gains for Tbilisi on this front either, however noting that Georgia must “transform itself from a post-Soviet state into a European-style democracy in terms of governance, politics and stability, in order to attract the North Caucasus republics.”

Mamuka Areshidze of the Tbilisi-based House of Free Opinion think tank is skeptical about the long-term substance of Saakashvili’s “United Caucasus” agenda, and thinks that the visa-free regime in particular is driven by short-term motivation. Although Tbilisi does not expect to cause major destabilization in the North Caucasus, he said, it does want “to exacerbate Moscow’s sense of insecurity in the North Caucasus; to create a certain discomfort.” Over the last year Tbilisi has intensified efforts to promote itself on the other side of the mountains and even to encourage anti-Russian sentiment. In December of 2009, for example, the “First Caucasian” Georgian television channel began broadcasting in the North Caucasus in Russian, and in February this year Tbilisi hosted an international conference dedicated to crimes committed against the peoples of the North Caucasus. Few in Moscow – or elsewhere, for that matter – would consider this a solid foundation for the creation of a peaceful Caucasus.

As is so often the case in relations between Tbilisi and Moscow, the elephant in the room is the international audience: both parties are engaged in a symbolic struggle reaching beyond the issues immediately at stake. In particular, Tbilisi’s opposition to Moscow’s two-decade-old bid to join the World Trade Organization is now drawing firm pressure from Washington. This backdrop and the desire to shed the label of occupation led Moscow, at the otherwise unproductive October 15 international Abkhazia and South Ossetia talks in Geneva, to announce an imminent withdrawal of its last checkpoint on Georgian territory beyond the established boundaries of South Ossetia. This measure marks Moscow’s desire, with an eye on the international community, to demonstrate a constructive attitude without making major concessions. Tbilisi’s “united and peaceful Caucasus” agenda and the withdrawal of the visa regime that falls within it may meanwhile be no more than a vain encouragement for Moscow to slip up.

This comment first appeared on RussiaProfile.org