The Autonomous Republic of Crimea turned 20 on January 20, 2011. On that day in 1991, residents of the Crimean Region voted in a referendum to restore the region’s autonomous status. The results of that referendum, the first in Soviet history, were very convincing: with 81% turnout, 93% voted to restore the Crimean Autonomous Republic, which existed from 1921 to 1945. Only Crimean Tatars were opposed, but most of them were still living in Central Asia, where Stalin had deported them in 1944, allegedly because some Tatars collaborated with Germans during WWII.

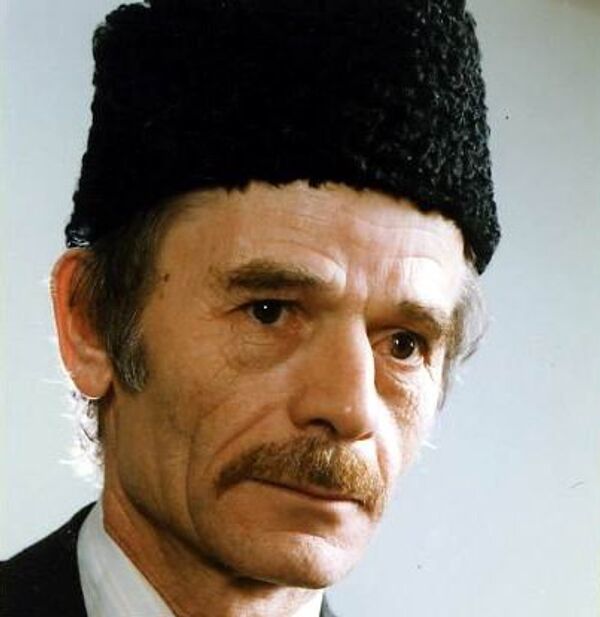

Mustafa Dzhemilev, a member of the Ukrainian parliament, the Supreme Rada, tells RIA Novosti correspondent Dmitry Zhmutsky why Crimean Tatars did not take part in the referendum and why they don’t support Crimean autonomy in its present form. An outspoken advocate of repatriating Tatars in Crimea, Dzhemilev spent 15 years in Soviet prison camps and was the recognized leader of the Crimean Tatars in the early 1990s. He remains the most influential Crimean Tatar politician to this day and also heads the Majlis, an unofficial organization that claims the status of central executive authority of the Crimean Tatars.

Crimean Tatars were the first during perestroika in the late 1980s to demand the restoration of Crimea’s autonomous status. As far as I know, the first public meetings demanding this were staged in 1987.

No, it was long before that. After WWII, the national movement of Crimean Tatars had two priorities: to return Crimean Tatars to their homeland and to regain the autonomy Crimea had before 1945. The Soviet government persecuted us, saying that we were anti-Soviet and pro-autonomy nationalists.

The decree on the Tatars who had lived in Crimea, enacted in September 1967, was quite an angry document that justified the deportation of Crimean Tatars. It said that Crimea’s autonomy should not be restored because the demographic makeup of Crimea had changed. Preparations for a referendum on Crimea’s autonomy began only in 1990 – a year before the dissolution of the Soviet Union – at the initiative of the Soviet Communist Party’s Central Committee.

Are you saying that the idea to hold the referendum came from Moscow?

Yes, of course. The question was phrased as follows: “Do you support the restoration of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic as a constituent entity of the USSR and a member of the Union Treaty?”

In other words, the referendum gave Crimea a chance to temporarily become an independent Russian republic if the Soviet Union were to fall apart, and then to join Russia. Many Soviet leaders later wrote in their memoirs that this was the outcome they had in mind.

Why did Crimean Tatars refuse to take part in the referendum?

We said firmly that until the indigenous population can return to their homeland, representatives of other nations have no right to determine the status of that land. This is why we boycotted the referendum.

As expected, most Crimean residents voted to restore autonomy, but this did not signify the restoration of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. When the Ukrainian parliament discussed the possibility of recognizing the results of the referendum in 1991, one of the main arguments in favor of Crimean autonomy was that it was one of the regions in Ukraine with a predominantly Russian population.

So it was not really about restoring Crimean autonomy. The focus was on the ethnic composition of Crimea, and the autonomous status was used to codify demographic changes that happened there since the deportation of the Crimean Tatars.

Do you agree that Crimea’s autonomous status prevented an ethnic conflict there in the 1990s?

Absolutely not. On the contrary, it fueled ethnic tensions, because Crimean Tatars were against a Russian autonomous region in Crimea.

Does the current form of Crimean autonomy meet the needs of the Crimean Tatars?

Of course not. After the establishment of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk said that first they would approve the autonomous republic, and then specify its status, taking into consideration the interests of all Crimean residents. But this is not what happened.

Instead, the Ukrainian authorities overturned the Crimean Constitution in 1994 and put an end to the presidency, greatly curtailing the autonomous republic’s independence. Is Crimea actually autonomous, or just on paper? Does it have powers other Ukrainian regions lack?

There are only minor differences between it and other Ukrainian regions. Kiev’s actions to curtail Crimean autonomy were justified: President Yuriy Meshkov (the first and only Crimean President, who held the post in 1994 and 1995 – RIA Novosti) was committed to making Crimea part of Russia, and even started establishing military agencies. Under him, Crimea was almost a sovereign state, which served to heighten tensions. Kiev responded harshly, for example by fueling clan tensions in the republic.

Were things good during the 20 years that Crimea was an autonomous republic?

There was nothing good about it for Crimean Tatars. Yes, an attempt was made in 1994 to introduce a system of quota-based representation of the indigenous population in the Crimean parliament and other bodies of power. But it only lasted for one four-year parliamentary term. Since 1998,

Crimean Tatars, who have settled across Crimea, have had essentially no chance of being elected to the Crimean parliament in first-past-the-post constituencies. Their current representation in government is three times smaller than the share of Tatars in the Crimean population.

Does Crimea really need autonomy? The neighboring region, Sevastopol, has fewer powers than any other Ukrainian region, yet this has not caused a disaster there.

We believe that Crimea should be autonomous but in the form that existed there before the deportation of Crimean Tatars. Crimea had two official languages then – Russian and Crimean Tatar – and the ethnic composition of the region was accurately reflected in all branches of power. But today Crimean Tatars suffer the most discrimination of any group in Crimea. We don’t want that kind of republic.