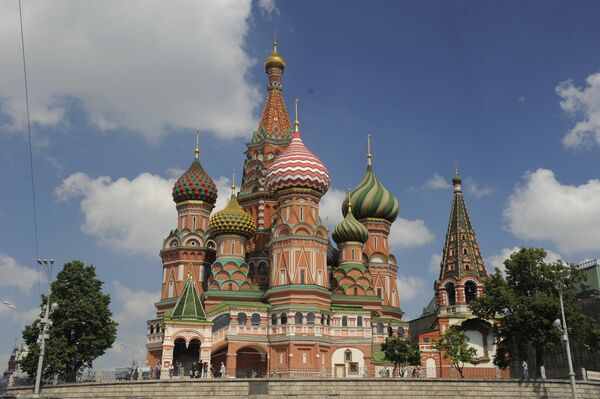

St. Basil's the Blessed (Protection Veil of Our Lady) Cathedral, better known as St. Basil's (Intercession) Cathedral (Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed), stands in the south part of Moscow’s Red Square above the sloping Moskva River bank, close to the Spassky Gate of the Kremlin. It was built in the middle of the 16th century on the order of Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible to commemorate the rout of the Kazan Khanate, a part of the former Golden Horde, and in thanksgiving for the victory.

Precise information about previous structures on the spot of the St. Basil's (Intercession) Cathedral has not come down to us as mediaeval Russian chroniclers made only sketchy and mutually contradictory references to wooden and stone churches, so there is a wealth of conjectures and legends.

According to one version, a wooden Trinity Church with seven transepts was founded on the sloping bank of the Moskva on the site of the future St. Basil's (Intercession) Cathedral soon after Ivan the Terrible returned from the Kazan campaign in 1552.

Metropolitan Macarius of Moscow, later canonised, advised Ivan the Terrible to build a stone church on the site. The basic idea of its architectural composition also belonged to him.

The earliest reliable reference to the construction of the St. Basil's (Intercession) Cathedral dates to autumn 1554. Presumably a wooden structure, it was built only to be dissembled six months later, giving room to a stone cathedral, whose construction began in spring 1555.

The cathedral’s architects, both Russian, were named Barma and Postnik, though some scholars conjecture that both names belonged to one man. As legend has it, Ivan IV the Terrible ordered the architects blinded after the church of fabulous beauty was built lest they create something even more beautiful and majestic. The legend was eventually exposed as groundless conjecture.

It took only six years to build the cathedral even though construction stopped in winter. A chronicle describes the miraculous appearance of a ninth side altar in the south part of the edifice after the construction was practically over. However, the ninth altar does not break the sophisticated symmetry of the building to prove that it followed the original idea of eight transepts (in fact, side churches) surrounding the central area. The cathedral was made of brick with a white stone foundation and basement, and some of the décor is made of white limestone.

The greater part of the works had been finished by autumn 1559. All side churches were consecrated on Intercession Day while the central part, the largest of all, was not ready yet, according to the chronicle.

Metropolitan Macarius blessed the cathedral again with the consecration of its central, Intercession church on July 12 (June 29 according to Julian Calendar), 1561.

Every side church was consecrated separately – particularly, the east one after the Holy Life-giving Trinity. Researchers do not know the reason to this day. According to one hypothesis, it was an allusion to the Holy Life-giving Trinity Monastery, founded in vanquished Kazan in 1553. According to another, it commemorated the wooden Trinity Church on the site of the new cathedral.

Another four side transepts were dedicated to the saints with whose days the landmarks of the Kazan campaign coincided: the storm of Kazan finished on the day of Sts.Cyprian and Justina, October 2/15; the Ar tower of Kazan was demolished on the day of St.Gregory the Illuminator of Armenia, September 30/October 13; the army of Yepancha the Khan’s son, which was hurrying to the rescue of Kazan from the Crimea, was routed on the day of St.Alexander of Svir, August 30/September 12. The fourth transept was consecrated to Sts.Alexander, John and Paul the Confessor the Patriarchs of Constantinople, also commemorated on August 30.

Three more transepts were consecrated to St. Nicholas’ miraculous icon found on the Velikaya River and known as Velikoretskaya, to St. Barlaam of Khutyn and to the Entry of Our Lord into Jerusalem. The central altar was consecrated to the Intercession of Our Lady as the principal and victorious storm of Kazan began on Intercession Day, the symbol of the Holy Virgin Mary’s protection of Christendom (1/14 October). The entire cathedral owes its name to its central part.

Chroniclers complemented the name of the cathedral with the specification “on the Moat” due to a broad and deep fortification moat dug along the Kremlin wall across Red Square in the 14th century, and filled with earth in 1813.

The cathedral has an unprecedented layout, with nine independent churches erected on basement single foundation. The eight side churches are joined to each other with vaulted interior galleries round the central church. All of them were originally surrounded by another, open gallery. The central church is crowned with a tall domed spire, while the side ones have vaulted ceilings with an onion dome above each.

The original detached belfry had three roof tents, with massive bells suspended in the arches.

The cathedral was originally topped by eight great domes with a small cupola above the central church. To emphasise the use of red brick, which was a fairly new and expensive material at the time, and to protect the building from harsh weather, its walls were painted on the outside in red and white imitating brickwork. The fire of 1595 destroyed the original domes and cupola, so we do not know what their roofs were made or covered with.

In 1588, a tenth church was added to the cathedral on the northeast side above the grave of St Basil the Blessed, God’s fool and miracle worker, who spent a long time on the cathedral construction site and bequeathed to be buried close to it. He died in 1557.

After he was canonised, Tsar Theodore, the son of Ivan IV the Terrible ordered a church built above his grave. It was a detached pillarless structure with a separate entrance.

St.Basil’s silver reliquary was lost in the Time of Troubles at the beginning of the 17th century. Daily services were established in the sanctuary soon after its opening. Its name spread to the entire cathedral in the 17th century, and has been its vernacular name to this day.

Fanciful cupolas replaced the burned roof and domes at the end of the 16th century.

An eleventh church was attached to the cathedral on the southeast side in 1672. It was a small sanctuary in memory of Ivan the Blessed, another venerated God’s fool of Moscow, who was buried on the cathedral grounds in 1589.

The cathedral exterior underwent major changes in the second half of the 17th century. A roof resting on brick arches and pillars replaced wooden shelters of the outer gallery, which had been frequently damaged during fires. A church of St. Theodosia the Virgin Martyr appeared above the porch of St. Basil’s Church. The formerly open white stone stairs to the upper tier were covered with porches under tented roofs resting on so-called “ramping” arches.

The first multi-coloured ornamental murals appeared at the same time on the new porches and the gallery pillars, outer walls and parapets, while the facades retained their original painting that imitated red brick. A tiled inscription in large yellow letters against a dark blue background belted the upper cornice in 1683, telling the story of the cathedral construction and repair in the second half of the 17th century. The inscription was destroyed during repairs a hundred years later.

The belfry was demolished in the 1680s to be replaced by a two-tier bell tower topped with an open platform for the bell ringer.

The fire of 1737 caused great damage to the cathedral, especially its south church. The murals were cardinally changed in the repairs of the 1770s-1780s. Wooden churches in Red Square were demolished to prevent further fires, and their altars were transferred to the cathedral grounds. Some of them were installed within the cathedral. At that time, the altar of the Three Patriarchs of Constantinople was reconsecrated in memory of St. John the Merciful, the Patriarch of Alexandria, while the Church of Sts Cyprian and Justina was renamed after Sts. Hadrian and Natalia. The churches regained their original consecrations in the 1920s.

The new interior murals, representing saints and scenes from their Lives, were repaired in 1845-1848 and at the end of the 19th century. On the outside, the walls were painted in imitation of rustication. The basement arches were filled with brick, and living quarters for the cathedral clergy were made in the west side of the basement. A wing was built to adjoin the bell tower to the cathedral, while St. Theodosia’s Church, the upper part of St. Basil’s Church, was made into vestry.

Though Napoleon ordered his artillery to blow up the cathedral in 1812, the Grande Armée made do with looting it. The cathedral was repaired and blessed immediately after the war, and the area around it was developed and surrounded with an iron lattice designed by famous architect Osip Bove.

The idea of restoring the original look of the cathedral was first voiced at the end of the 19th century. A commission was established to unite top architects, artists and scholars, who drew up research and restoration guidelines. However, the programme was never implemented due to lack of funds and the ensuing October Revolution, which brought economic dislocation in its wake.

The St. Basil's (Intercession) Cathedral was among the first objects to receive government protection in 1918 as a monument of national and global purport. It was opened to visitors as a museum of architectural history in May 21, 1923. Nevertheless, services at St. Basil’s Church continued until 1929.

In 1928 the St. Basil's (Intercession) Cathedral received the status of a branch of the State History Museum, which it retains to this day.

The cathedral regained its original exterior and some of its churches the 16th-17th century interiors following large-scale research and restoration work launched in the 1920s.

The cathedral has seen four comprehensive restorations since then, involving architects and painters. Particularly, the original 16th century wall painting imitating red brick was restored on the outer walls and in the churches of the Intercession and St. Alexander of Svir.

A construction chronicle was discovered in the central church during unprecedented restoration work in the 1950s-1960s. The precise date of the end of construction became thus known. It was July 12, 1561, Sts. Peter and Paul’s Day. The iron cupola roofs were replaced by copper for the first time. The innovation has proved its worth – the roof stays intact for decades.

The restored iconostases of four churches almost entirely consist of 16th-17th century icons, which include outstanding masterpieces, including the 16th century Trinity. Other gems of the collection are the 16th-17th century icons of the Vision of Sacristan Theresius, St. Nicholas Velikoretsky with Life, St. Alexander Nevsky with Life, and the icons of St. Basil the Great and St. John Chrisostom from the original Intercession Church. 18th-19th century iconostases are extant in the other cathedral churches.

Two of them were transferred from the Kremlin cathedrals in the 1770s: the choir screens in the Church of the Entry into Jerusalem and in the central church.

A 17th century mural discovered in the outer gallery under later layers in the 1970s gave grounds for the restoration of the original ornamental murals on the facades.

1990 was a landmark year for the cathedral. UNESCO granted it the status of World Heritage Site, and divine services were renewed at the Intercession Church. A year later, the cathedral was legally transferred into joint use by the State History Museum and the Russian Orthodox Church.

The restoration of St. Basil’s Church interior, icons and murals finished in 1997. Closed since the late 1920s, the church reopened to tourists and worshippers, and divine services are celebrated there again.

Liturgies are celebrated by the Patriarch or bishops at the cathedral on its principal patron saints’ days – the Intercession and St. Basil’s Day. An Acathistos is also read in front of his reliquary every Sunday.

Seven cathedral churches were fully restored, façade murals renewed, and the distemper murals of the inner gallery partly restored in 2001-2011. In 2007, the cathedral was nominated for the Russia’s Seven Wonders competition.