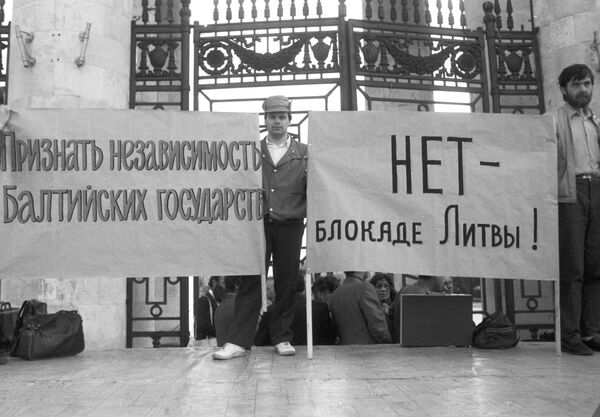

Twenty years ago, on September 6, 1991, the Soviet Union recognized the independence of the Baltic republics: Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. The empire was breathing its last, many of its agencies were idling and decisions which would have caused an outcry before were made routinely and without much ado. The recognition of the three Baltic countries' independence was sealed by a resolution of the USSR State Council, which did not survive long in the deep shadow of the Politburo and Secretariat of the Soviet Communist Party's Central Committee.

The Soviet Union pulled out of the Baltics without ceremony - a classic case of "French leave." Yet it was a highly significant move, which complicated the work of the commissions later set up in the Baltic counties to calculate the damage caused by the Soviet occupation. It also complicated the simplistic historical revisionism of the Baltics' post-Soviet authorities, according to which the Soviets were no better than the Nazis and left them no hope of independence.

It appears that the Soviet Union was better, as it did finally, after 50 years, recognize the independence of the three Baltic countries. This created a solid foundation for Russia's relations with them. The policy of President Boris Yeltsin, who supported the independence of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia long before it was officially recognized, no longer clashed with the legislation of the Soviet Union, whose legal successor Russia is.

Although it formalized the Baltics' independence, which they actually gained in 1990, the USSR State Council did not accept their interpretation of the events of 1939-1989 as an illegal occupation. Moscow was unwilling to condemn the Baltic countries' Soviet period in toto.

Historians are divided over the events of 1939-1940 but not along national or ideological lines.

Natalya Lebedeva, a researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences' Institute of General History, who first investigated the Katyn tragedy and also analyzed the records of 1939-1940 in the Baltics, does not consider the 50-year Soviet rule as occupation. Lebedeva argues that occupation implies temporary seizure of a country's territory during a military conflict. It is true that the incorporation of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia into the Soviet Union was not voluntary, but there were no other elements of occupation, such as hostilities between two armies, subsequent capitulation and privileges granted to occupiers. In this particular case, history does not fit the bad guy/good guy model.

Russians do not deny that the Soviet power was established in the three Baltic countries in 1940 and then again in 1944. "The regime established in the Baltic countries as a result of the Soviet intervention was not an occupation but a Soviet-style Communist government," historian Yelena Zubkova, a researcher at the Russian Academy of Science's Institute of Russian History, writes in her book, "The Baltics and the Kremlin." "It was the beginning of a change much more dramatic than any military occupation."

Recognition of that fact could become the basis for developing mutual understanding and new relations between Russia and the Baltic countries. The USSR State Council offered that opportunity 20 years ago, but it was missed due to the Soviet legacy. Suffering from a shortage of many commodities, the Baltic countries blamed their problems not on the economic and political absurdity of the Soviet and post-Soviet periods but on their neighbors, who speak a different language and have different customs.

After the re-establishment of Soviet power in the Baltics in 1944, the Soviet government erected a small "iron curtain" between these republics and the rest of the Soviet Union. It lifted restrictions on travelling to the Baltics only in 1946, a year after the victory in WWII, and immediately people from the Pskov, Novgorod and Leningrad regions rushed to Estonia to buy flour and bread. Prices soared in Estonia, angering the locals. Estonians, ignorant of the harsh reality of Soviet life, did not know that Russia suffered from even worse food shortages caused by the war and 15 years of collective farming.

Furthermore, the idea that "one's rights come at the expense of the rights of others," as Zubkova writes in her book, became widespread during the Soviet period.

Back in the 1950s, when Russians appealed the Soviet authorities for help in the face of discrimination in the Baltic countries, the national leaders such as Antanas Snieckus and Mecys Gedvilas in Lithuania claimed that the "Leninist-Stalinist nationalities policy" made it impossible to simultaneously use two languages - Russian and the national language - for issuing documents and keeping state records.

Many years later, this problem still has not been resolved. Neither the Baltic nations nor Russians understand that other people's rights are the inalienable part and a guarantee of their own rights.

The views expressed in this article are the author's and may not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.