RussiaProfile.Org, an online publication providing in-depth analysis of business, politics, current affairs and culture in Russia, has published a new Special Report on the 20 Years since the Fall of the Soviet Union. The reports contains fourteen articles by both Russian and foreign contributors, who try to analyze the many changes that have taken place in Russian society since then and attempt to answer two perennial questions: was the collapse of the USSR the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”, as Vladimir Putin once said, or a blessing for its people? And how far has present-day Russia departed from its Soviet past?

The Number of Small Businesses in Russia Is Catastrophically Low.

It seems plausible to presume, with the benefit of hindsight, that the economic inertia that accumulated during 70 years of communist rule over the Soviet Union was positive proof of the empire’s inevitable demise. Yet the cascading economic events that preceded—and in some cases, outlived—the collapse of the Soviet Empire, had been so overwhelming that neither economists nor the main protagonists expected such a disconcerting finale.

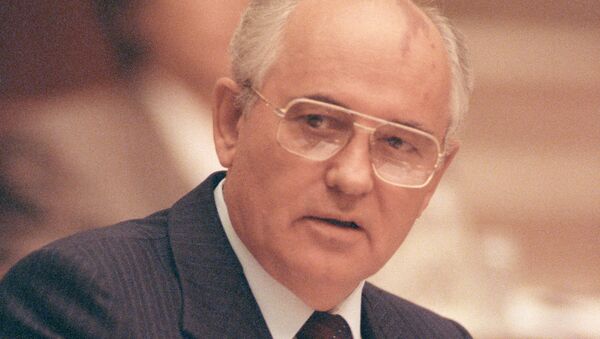

When Mikhail Gorbachev, the first and last president of the Soviet Union, announced a series of half-hearted stop-gap economic measures as part of his perestroika, Communist Party apparatchiks were quick to warn that opening capitalist floodgates would unleash economic and political forces way beyond his control. Well aware of the disruptive potential lurking in the country’s command economy, Gorbachev in 1987 proposed the formation of privately owned, profit-oriented cooperative enterprises to supplement and even compete with state-run projects. The thrust of his proposal, like Lenin’s quasi-capitalist New Economic Policy of 1921, was to revitalize the Soviet Union’s laggard consumer goods and services industries.

But the move, as innocuous as it now seems, launched the Soviet Union on the long and tedious journey toward capitalism. The new co-ops, Gorbachev thought, would pay taxes and might even forestall large-scale social discontent by absorbing some of the 15 million workers who might lose their jobs in a much-needed pruning of the bureaucracy. By 1989, the ranks of Soviet co-ops had swelled to 48,000. Though they accounted for just one percent of the country’s economy, the co-ops employed some 770,000 workers who provided an odd assortment of services, ranging from animal grooming, auto repairs, computer maintenance, hairstyling, plumbing, and translating to operating pay toilets. “In essence, Gorbachev’s co-operative movement was the foundation of Russia’s democratic capitalism and also the bane of command-and-control economy,” said Vladimir Pribylovsky, head of the Panorama think tank.

Despite Gorbachev’s strong support for the co-ops, however, a number of events that unfolded in the early days of the movement provided a lot of ammunition to skeptical party apparatchiks, who had adopted a wait-and-see attitude. Most Soviet citizens were quickly dismayed by high prices in the private shops, which typically were at least twice the going rate at state stores. Many had grumbled about their economic system, but they were nonetheless wary of any experiments that could allow some individuals to reap huge profits at the expense of others. In December 1988, at least two Moscow cafes were vandalized, and in January 1989, thugs attacked another private restaurant, knifing customers and setting it on fire. Faced with violence and extortion threats from organized criminal groups, some co-op owners started paying bribes to the racketeers or offered them phony jobs in return for protection, or “krisha” (a roof)—a practice which set a perfect stage for what would later be known as Russia’s “Wild East” of the early 1990s.

The rise of oligarchy

The 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union ushered in an era of economic desperation with a dangerous mix of organized crime, political cronyism and fantastic business deals forged overnight. The main challenge facing Boris Yeltsin, who became the first president of the Russian Soviet Socialist Federal Republic in 1991, was converting the world’s largest command economy into a free-market one through a program of radical economic reform and privatization. To achieve this, he turned, in late 1991, to the advice of Western economists, including Western institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the U. S. Treasury Department. A standard policy recipe that came to be known as “shock therapy” was put together, intended, as it were, to liberalize prices and stabilize the state budget.

Yeltsin doggedly pushed his package of shock economic reforms even as his critics alleged that, with the help of his top allies—Yegor Gaidar, a 35-year-old economist, and Anatoly Chubais, a leading privatization advocate—state enterprises and natural resources were being sold for bargain prices, while the rest of the Russian population combated starvation, homelessness and destitution. Yeltsin launched a program of free vouchers in late 1992 as a way to give mass privatization a jump-start and create political support for his economic reforms. Under the program, all Russian citizens were issued vouchers, each with a nominal value of around 10,000 rubles, for purchase of shares in former state enterprises. However, the vouchers were quickly snapped up by wheeling-dealing intermediaries, leaving both the program and the economy in tatters. Chaos ensued. Russia’s GDP fell by 50 percent, vast sectors of the economy were wiped out, inequality and unemployment grew dramatically and incomes plummeted.

In 1995, Yeltsin prepared for a new wave of privatization, offering stock shares in some of Russia’s most valuable state enterprises in exchange for bank loans in a desperate effort to finance Russia’s growing foreign debt and gain support from the Russian business elite for his 1996 reelection bid. Though the program was promoted as a way of simultaneously speeding up privatization and ensuring the government a much-needed infusion of cash for its operating needs, many Russians saw the deals as giveaways of valuable state assets to a small circle of tycoons who came to be known as “oligarchs” in the mid-1990s. Seventy-five year-old Tatiana Pivovarova, a retiree who lost her investment in privatization vouchers, called the program a conspiracy against Russia. “Call it what you will, it was a scheme, a pyramid,” Pivovarova said. “A tricky possession of our vouchers simply gave way to an even trickier possession of our properties.”

Meanwhile, some businessmen, including Boris Berezovsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Vladimir Potanin, Vladimir Bogdanov, Rem Viakhirev, Vagit Alekperov, Alexander Smolensky, Victor Vekselberg, Mikhail Fridman and later Roman Abramovich, who controlled major stakes in former state enterprises, were believed to be Yeltsin’s strong supporters, but not without help from the media. But support from the oligarchs did not help Yeltsin avert political and economic crisis in 1998, as his government defaulted on its debts, causing financial markets to panic and the ruble to collapse. In the eyes of his most vicious critics, the 1998 financial crisis was retribution for all that was wrong with Yeltsin’s reforms, in particular, his flirtation with capitalism.

The seismic changes in Russia rippled across the wide expanse of former Soviet republics, where most newly emerging states were struggling to swap central planning for market economies. For many, it was to be a mission impossible. Having long been part of the tsarist Russian empire, most of the independent nation states lacked elements of private business and ownership, let alone traces of independent civil society. As in Yeltsin’s Russia, private businesspeople and rent-seeking officials found ways to exploit the situation—and imperfectly designed privatization programs—to amass huge wealth, wrote John Thornhill in the Financial Times. “As a result, an emergent oligarchy of business-political clans was able to capture the state in Russia and other post-Soviet nations,” Thornhill said.

In the absence of a role model, goal and incentive for economic reforms, authoritarian regimes emerged in some of the ex-Soviet Republics. “Most of the post-Soviet states are corrupt states that have as their purpose allowing the elites to enrich themselves through corruption,” said Anders Aslund, a Swedish economist who advised the Russian and Ukrainian governments in the early 1990s. “Authoritarianism is the means of making sure that they can maintain this.”

From disunion to Customs Union

Rebuilding broken economic ties between former Soviet states has been the preoccupation of Prime Minister Vladimir Putin since he assumed the Russian presidency in 2000. “He who does not regret the break-up of the Soviet Union has no heart; he who wants to revive it in its previous form has no head,” Putin once said. In 2000, Putin signed an agreement with half a dozen countries to create the Eurasian Economic Community, or EurAsEc, “which has largely remained a talking shop,” Thornhill said. But since 2009, Putin changed strategy, pursuing a deeper integration with a few former Soviet states by luring them into a Customs Union modeled somewhat after the European Union’s common market. Kazakhstan has joined by conviction, Belarus, through persuasion, while Ukraine continues to rebuff the invitation to join.

Russia wants a single common economic space that will not only bring the former Soviet states closer together, but could also serve as a buffer against global economic crises and a safe haven for potential investors. Therefore the leaders of Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus took further practical steps toward integration at the beginning of July this year by abolishing customs controls on the union’s internal borders and moving customs control of goods and vehicles crossing their territories to what have now become the union’s external borders. By January 2012, the member-states are expected to transform the union into a “common economic space” that would ensure free movement of goods, services and capital across a single market of 165 million people representing 60 percent of the former Soviet population.

Removing the customs checkpoints “is not just a technical formality,” Putin said in July. “This is truly an event of great interstate and geopolitical significance. For the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a step has been taken to restore economic ties within the post-Soviet space,” he said. Writing for the Financial Times, Neil Buckley said the deepening Customs Union has the typical advantages of stimulating business development by removing trade barriers. “It could also help restore horizontal links between industries and enterprises severed when the Soviet Union collapsed. Moreover, by tying Kazakhstan—former Soviet Central Asia’s most successful economy—to Russia, it counters growing Chinese influence in the region. Neighboring Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have also expressed interest in joining,” Buckley said.

Leading experts contend that a sudden surge in global energy prices in the early 2000s has allowed Putin to achieve more in foreign and domestic policies than either Gorbachev or Yeltsin. But windfall oil revenues could also be a double-edged sword for countries wanting to build fully-fledged capitalism. “Economic reforms were well underway in the first three years of Putin’s presidency,” said Nikolai Petrov, a political analyst at the Carnegie Moscow Center. “But as the state became awash with revenues from oil and gas, the leadership decided there was no longer a need to undertake new reforms.” The classic discord between sudden affluence and economic reforms, known as the “oil curse,” has also been plaguing other resource-rich ex-Soviet states. With the possible exception of Kazakhstan, which carried out some market-friendly reforms, non-energy sectors in other countries such as Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan have languished as their leaders resisted full-scale economic reforms.

New realities of global capitalism, however, may have persuaded countries like Russia to have second thoughts about economic reforms, despite windfall oil revenues. Russia’s current leader, President Dmitry Medvedev, has vowed to reform, modernize and diversify the country’s resource-based economy to avert the kind of economic stagnation that knocked down the Soviet system. This alone would not mean that capitalism has reached a point of no return. “There are certainly no comparisons between then and now,” said Peter Necarsulmer, the chairman and CEO of the PBN Company and one of the first Americans to discover capitalist proclivities in Russia in the early 1990s. “However, the Russian leadership still needs to pay more than lip-service to the development of the country’s limited capital markets.” What still sets Russia apart from many other developed and developing capitalist systems, Necarsulmer said, is the small, almost insignificant number of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). “It is not only because they generate the most sustained economic activity, but so many of the innovations and modernizations and diversification aspects of the economy that the Kremlin commits to come out of small-sized businesses,” he said. However, Medvedev’s main challenge may yet be how to infuse new economic thinking into a people brought up to expect much from the state. “That’s the toughest part,” Necarsulmer said. “And it is amazing how much of the old thinking stuff continues to this day.”