In the midst of a snowstorm hovering around the 62nd floor of the colossal Federation Tower, socialite turned opposition activist Ksenia Sobchak is hosting a discussion to debate future strategies for Russia’s nascent civil society, emboldened by this winter’s mass protests against the rule of President-elect Vladimir Putin.

"Civil society is the only genuine opposition to the authorities in Russia right now,” Sobchak, 30, a former Playboy cover girl, tells an invited audience of Moscow hipsters fiddling with their smartphones and tablet PCs. “And the authorities, for the first time in twelve years, have sensed a threat.”

President Dmitry Medvedev responded to the outbreak of mass protests across Russia last December with proposals for a series of reforms, including a relaxing of the current prohibitive requirements for registering political parties, judicial reforms and a new independent nationwide television station. But Sobchak, like many in the opposition, is wary.

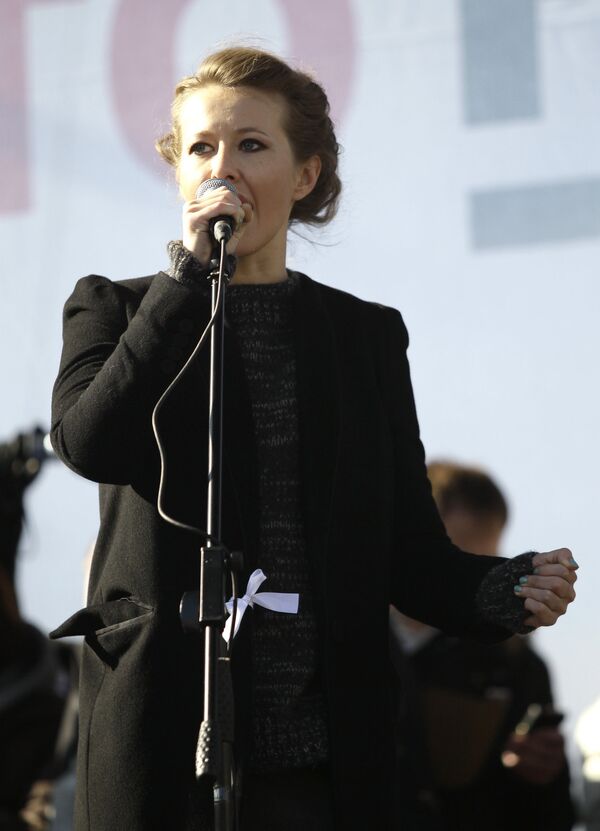

“Our task now is to ensure that any liberal reforms undertaken are genuine,” says Sobchak, dressed all in black and nodding occasionally at friends in the audience. “We really need to be on our guard.”

And while she admits the protest movement is in danger of entering a new period of “stagnation” after “letting off steam” in recent months, Sobchak also predicts the demonstrations were merely the preclude to something much more dramatic.

“Civil society has lifted the lid off the pot to see what’s simmering in there,” she says, as the far-off lights of Moscow traffic shimmer through the wall-length windows of the BrainON discussion club. “It’s not boiled over yet, but I have no doubt it will. Maybe in two years, maybe this summer, maybe in six years. And when it does we have to be prepared to decide what comes next – a tragedy or the liberation of our country?”

As the wealthy daughter of Anatoly Sobchak, the late mayor of St. Petersburg and the man who gave Putin his first break in politics when he employed him at City Hall, Ksenia Sobchak’s sudden conversion from tabloid staple – “Russia’s Paris Hilton” – to outspoken opposition figure has been met with a degree of suspicion and, even, outright hostility. Her appearance at a Moscow protest rally in December was greeted with jeers and catcalls from a large section of the crowd.

But Sobchak was back on the stage at last Saturday’s rally in the capital, the last before Putin’s inauguration in May, to urge protesters to determine concrete goals for the movement aside from the now-tired, if still highly charged, slogans of “Russia without Putin!” and “Fair Elections!”

“We know what we’re against. But now we have to show what we are for… If we don’t, the whole battle will have been senseless,” she said. “We need legal reform, free media, social support for the youth and comprehensive political reforms.”

But despite the jeers that again sounded out when she began her speech, there seems little doubting her commitment to the drive for political change in Russia.

“I think she’s genuine,” said Vera Kichanova, 20, opposition activist and a newly-elected Moscow municipal councilor. “It seems unlikely she’d be doing all this for fame, which she already has plenty of.”

Like many of the leaders of Russia’s protest movement, Sobchak was a child when the Soviet Union collapsed, and she pours scorn on the country’s established political players and what she calls their inability to recognize that times have changed.

“They are like a fifty-year-old woman who still goes around in a mini-skirt,” she says. “It’s difficult for them to realize their time is up. Even they are tired of their own hypocrisy.”

Sobchak is an established TV presenter both loved and derided in equal measure for her hosting of popular reality shows, but her latest venture was far more serious, at least while it remained on air.

Her political show on MTV Russia - “State Department 2” - was pulled after just one episode, to which she had invited opposition Left Front movement leader Sergei Udaltsov and protest leader Yevgenia Chirikova. MTV Russia said their research had indicated that their audience was uninterested in politics. Sobchak said it was because she had asked anti-corruption blogger and opposition figurehead Alexei Navalny to appear on the next show.

But Sobchak’s longing for meaningful political change in Russia is tempered by sober pragmatism.

“The only thing the authorities are afraid of is 100,000 people on the streets and an Orange Revolution,” she says, a reference to the 2004 uprising in the former Soviet republic of Ukraine. “But while we can pressure the authorities on some things, like judicial reform, there are some issues they will not gave way on, like new presidential and parliamentary elections.”

“If we insist, this is the road to revolution – and I am against revolution.”

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ and may not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.