The first time I saw Alexander Shishkin, the greatest Adolf Hitler lookalike in the history of the planet, I was in awe. This tall, cadaverous man didn’t just look like Hitler, he looked like a Hitler that had died and been dug up again. It was eerie: the sunken cheekbones, the severe parting and of course the black moustache were almost enough to persuade you that Hitler was indeed back from the dead.

This was in 1997. I’d see Hitler on Red Square, where he and Lenin hung out waiting to have their pictures taken with tourists. Lenin was frequently drunk, and leering. Hitler was sober. Then one day in the early 2000s Hitler disappeared. I sometimes wondered what had become of him.

Last week I found out. He had returned to his home city of Tashkent in Uzbekistan, where he spent the last eleven years of his life living on a pension of $17 a month. Then he died. The obituaries had few details, just his real name (the first time I had heard it) and a few facts: he was the son of a Red Army pilot; he used to appear on stage with the heavy metal group Korroziya Metalla; he was once photographed with Boris Yeltsin.

I wanted to know more. So I did some research using Russian language sources and was able to flesh out the skeleton of his strange life.

Shishkin’s father was indeed a Red Army pilot. But he was shot down in 1941 and spent the war in a POW camp. Once it was over he was condemned to 25 years in the Gulag as an “enemy of the people” and his son was prevented from entering educational institutions. Eventually he trained in aeronautics, and then again in theater criticism, graduating in 1979. But Shishkin never worked in his specialty: instead he joined Uzbekfilm as a “simple worker,” scraping by on five rubles a day (extras made six).

And so Shishkin eked out this dismal living, and he was only occasionally bothered by people telling him that if he grew a moustache he would look just like Hitler. He married; had a daughter; got divorced. Then he played Hitler in a movie in which the Fuhrer had survived the war and was running a restaurant in Kazakhstan, playing the accordion for customers while Eva Braun danced. In 1990 he flew to Leningrad to participate in a lookalikes contest. There were many Alla Pugachevas, Lenins and Saddam Husseins. Shishkin was the undisputed champion among the Hitlers.

And so a star was born, of sorts. Shishkin returned to Tashkent to play Hitler in local films, before embarking on a tour of the USSR with other doubles and the cheesy pop singer Igor Talkov. Everybody wanted his picture taken with Hitler. In 1993 he appeared in a movie, “Cage” which was aired on Channel One, making him even more famous, but he remained hungry and impoverished. In 1995 he met Spider, leader of the heavy metal group Korroziya Metalla. Spider wrote a song for him- Nicht Kaput, Nicht Kapitulieren - and Shishkin was a regular fixture at the band’s concerts until 1998, snarling in German at the audience, which responded with boos and Nazi salutes. But Spider was “pathologically stingy” and Shishkin still had to scrape by on the money he made posing for photographs on Red Square.

By the year 2000, the weight of history was starting to crush him. Lenin, also from Tashkent, was locked up in an insane asylum for a while. But on his release he went to the Arbat, where on Victory Day he and Nikolai II made $1,000 each from posing for photographs. Hitler on the other hand was attacked by cops, chased and beaten, or simply abused: “You started the war! You, Hitler, get out of here!”

Exhausted, alienated, lonely and depressed, Shishkin left the cold, gray megalopolis for the sunny skies of Tashkent in 2001. There he was promptly ripped off, selling his ground floor apartment for $3,000 when, he subsequently learned, it was worth around $60,000. He was incredibly poor, but his Uzbek neighbors took care of him, sharing a bowl of plov and whatever else they had with this strange Russian “uncle”. He rode the trams of Tashkent in full Hitler gear, attracting attention and smiles. “The Uzbeks don’t know Hitler,” claimed Shishkin. Those who did invited him to their weddings.

On New Year’s Eve Shishkin broke an arm and a leg. No source I have found explains how this happened. His suffering lasted three months before he died from “complications.” It was a bad death after a difficult, yet interesting life. His neighbors and friends spoke well of the Hitler from Tashkent. He was a “quiet, honest person,” said the Uzbek writer Rifat Gumerov, “with a purely soviet upbringing”. He had been planning a return to Moscow, Gumerov added. But having “flourished” in the nihilistic 90s, and then disappeared in the cynical 2000s, I doubt there would have been a place for him in the new world that is being born, whatever form it finally assumes.

RIP.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and may not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

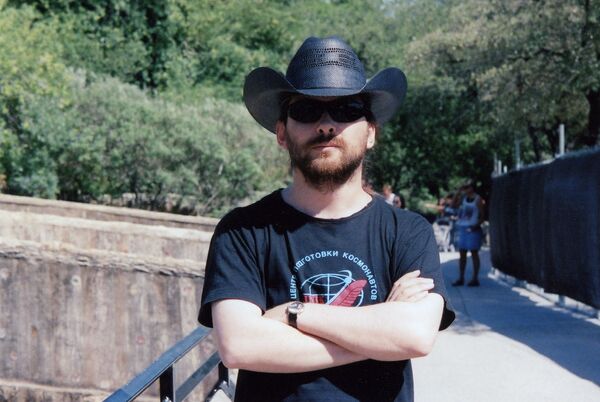

What does the world look like to a man stranded deep in the heart of Texas? Each week, Austin- based author Daniel Kalder writes about America, Russia and beyond from his position as an outsider inside the woefully - and willfully - misunderstood state he calls “the third cultural and economic center of the USA.”

Daniel Kalder is a Scotsman who lived in Russia for a decade before moving to Texas in 2006. He is the author of two books, Lost Cosmonaut (2006) and Strange Telescopes (2008), and writes for numerous publications including The Guardian, The Observer, The Times of London and The Spectator.

Transmissions from a Lone Star: World Goes Crazy, Gorilla Makes a Break

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Cross-Cultural Comparison of Russian and American Crime

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Beware of Falling Space Rocks!

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Notes on the Landscapes Spotted in the Backgrounds of News Reports

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Russia in Revolt as Viewed from Afar

Transmissions from a Lone Star: A Young Person's Guide to Russian Politics

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Learn Japanese the World War II Way!

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Scotland’s Bid for Independence Explained!

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The art of naming