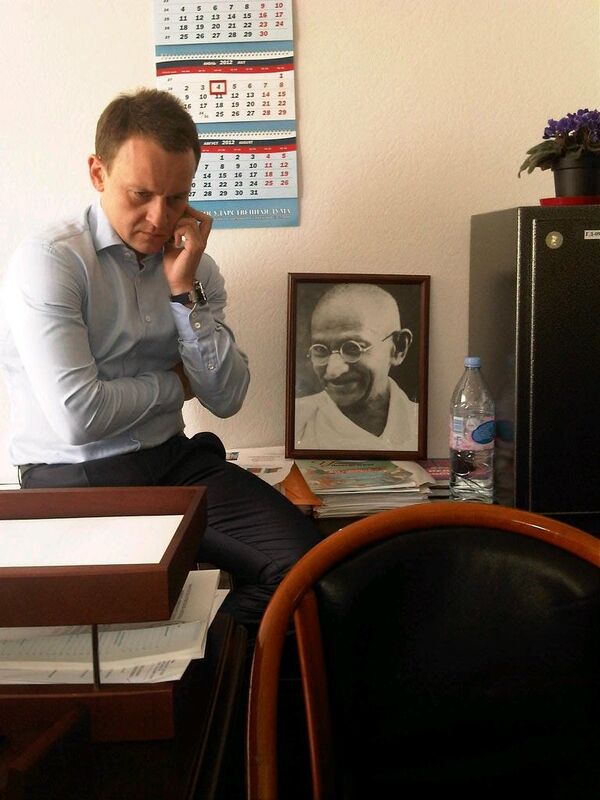

It comes as a surprise to discover that United Russia deputy Alexander Sidyakin, author of a recent controversial new law that drastically raises fines for violations of regulations governing protests, is a big fan of the late Indian civil rights activist Mahatma Gandhi.

“I like his tactics of non-resistance,” he says, sitting before a black-and-white framed photograph of Gandhi in his office in Moscow’s State Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament.

Sidyakin, 35, has been vilified in recent months by opposition figures over what critics say is his role in a Kremlin crackdown on unprecedented protests against the rule of President Vladimir Putin.

“I got angry, of course, when I first read all this bad stuff about myself online,” he admits with a shrug. “But now…”

“Anyway,” he goes on. “Opposition figures and liberal journalists often don’t even read the texts of laws. They are just, straight off, ‘he is bad, he supports the regime.’ There is a lot of hysteria and, well, trolling.”

NGOs and 'Foreign Agents'

Sidyakin’s latest proposed law would see “political” NGOs funded with money from outside Russia forced to declare themselves “foreign agents” or see their members face huge fines or jail time. It would also subject the organizations to much stricter financial checks.

The draft law has met with fierce opposition from critics who say the term “foreign agent” is a near synonym for “spy’ in Russian and would lead to the discreditation of human rights groups.

And the country’s oldest rights organization, the Moscow-Helsinki Group, said earlier this week it would close down its offices rather than comply with the law. Russia’s Public Chamber also said on Thursday that it would not support the bill - which has also been criticized by the Kremlin’s own rights council - in its current form.

But the author of what has proven to be one of the most controversial bills in modern Russia dismisses these concerns. “I think the idea that ‘foreign agent’ means ‘spy’ is more of a hangover from the Soviet period in which our parents grew up,” he says.

“I don’t think younger generations see the expression this way. We should try to get over Cold War terminology. I believe there is nothing insulting in this term.”

Sidyakin says though that the law is a response to counter what he calls attempts by the United States to “affect Russian politics.” He singles out the independent election monitor Golos as an example, citing at a parliamentary committee hearing on Wednesday the “$2 million given to the organization in 2011 to dirty the Russian authorities.” Golos, which monitors alleged election violations in Russia, freely admits to receiving funding from abroad and members have said Russian businessmen are afraid to donate for fear of repercussions.

Sidyakin’s views echo those of Putin – another admirer of Gandhi - who has accused the United States of spending millions of dollars to support the country’s opposition forces. Putin also once famously called Russian NGOs engaged in politics “jackals.”

Protest Law - Emotional Reaction to Riots

Sidyakin, who was only elected to parliament for the first time in December 2011, denies allegations that he was prompted “from above” to draw up the laws.

“This was my decision, my personal, legal initiative,” he says. “The protest law was a reaction to the clashes with police on May 6 at [downtown Moscow’s] Bolotnya Square, when protesters broke through police lines and twenty riot police officers were injured.”

“No government in the world would put up with attacks on police. This law makes those who organized protests responsible for attacks on police, if they call for or fail to prevent clashes.”

One of the co-authors of the bill, United Russia lawmaker Anton Krasin, said on Wednesday that the May 6 clashes - which came on the eve of Putin’s inauguration for a third presidential term - were “funded by money from abroad.”

Sidyakin, despite his belief that the United States is funding efforts to topple Putin, is more cautious. “You know, you can’t exclude anything,” he says. “But it would probably be incorrect to assert this.”

The law on protests was fast-tracked through parliament and entered into force early last month. It raised the maximum fine for a “violation of the established rules of conduct” at protests to 20,000 rubles ($620) - a twentyfold increase. Organizers of protests that result in damage to person or property will face maximum fines of 300,000 rubles ($9,200).

But Sidyakin had initially wanted much higher penalties, calling, for example, in the original draft bill for fines up to 1.5 million rubles (just over $46,000, or some five times higher than the average yearly salary in Russia) for organizers of protests that turn violent.

“This was an emotional reaction,” he admits. “The law that was approved was altered drastically from the one I first submitted…In the end we got a normal law that meets all European norms.”

Twleve Years of Putin 'Not Enough'

A native of northern Russia’s republic of Karelia, Sidyakin began his career in politics in the first decade of the 21st century in the Urals city of Ufa, where he headed at the tender age of 28 the regional branch on the now-defunct Party of Pensioners. He made a failed attempt to gain election to the Duma in 2007, as a candidate for the quasi-opposition party A Just Russia, before achieving his aim with United Russia in last December’s disputed parliamentary elections.

He laughs when asked what he makes of opposition discontent over the 12-year-rule of Putin. “I’m a United Russia lawmaker,” he says. “What kind of answer do you expect from me? Twelve years is not enough. Putin has, you know, consistently high ratings.”

And Sidyakin waves aside arguments by protest leaders that Putin’s power is solely down to a monopoly of national television. “There is the Internet,” he says. “And I often meet opposition figures on NTV, a federal channel.”

Sidyakin then sidesteps a question on whether or not the demonstrations that have rocked Moscow were triggered by Putin’s controversial decision last autumn to swap posts with then President Dmitry Medvedev and cites instead a “common, global trend” toward protest.

“Things have changed. If before people had to go through real crisis that affected their salaries, living standards and so before they would attend protests, then now this is no longer true.”

Navalny - Swindler

Sidyakin is unequivocal though on his dislike for the opposition’s figureheads, such as anti-corruption blogger Alexei Navalny, the man who coined United Russia’s popular nickname “the party of swindlers and thieves.”

“Navalny,” he says, spitting out the name of the protest leader, “is a swindler himself. How can he label two million members of United Russia all swindlers and thieves? Doctors, teachers, cultural figures – are they all swindlers? This comment will backfire on him.”

“Of course there is corruption among some individual officials within United Russia,” he admits. “This is something that has penetrated every sphere of life. But we can’t define United Russia as a whole as corrupt mechanism.”

He reserves particular scorn however for socialite dissident Ksenia Sobchak, the daughter of Putin’s late political mentor - St. Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak - mocking her overnight transformation from sometime Playboy model to anti-Putin activist

“Do you really think she is protesting against something?” he sneers. “This is all just PR. It’s all for, you could say, the sake of more Twitter followers.”

“I assure you,” he adds, in a statement that mixes real venom with a show of startling honesty. “All this democratic rhetoric…if the opposition takes power they will immediately become exactly the same as us. Perhaps even worse.”

“They will also become subjects of criticism,” he expounds. “The authorities are not a $100 bill,” he laughs. “Not everyone is always going to like them. But when people see today’s opposition, when they realize that these people could come to power, they make a choice in favor of the current authorities.”

Free Pussy Riot

Sidyakin offers unexpected support for the three members of the all-female punk group Pussy Riot, who have been imprisoned since March awaiting trial over an anti-Putin protest in Moscow’s largest cathedral.

“There is no need to sentence them to jail time,” he says after a long pause in which he considers his response. “They’ve been behind bars for long enough already.”

It’s an unexpected statement from the man who has become a bogeyman to the anti-Putin movement.

“This is though,” he makes clear as his mobile phone begins to ring, signaling the end of the interview, ‘my personal opinion and not the stance of United Russia.”