“What’s this? A prison?” asks the taxi driver, nodding at the barbed wire and imposing red brick walls. “Yeah, a women’s detention center,” replies Pyotr Verzilov, political art activist and husband of jailed Pussy Riot member Nadezhda Tolokonnikova. “Not a happy place.”

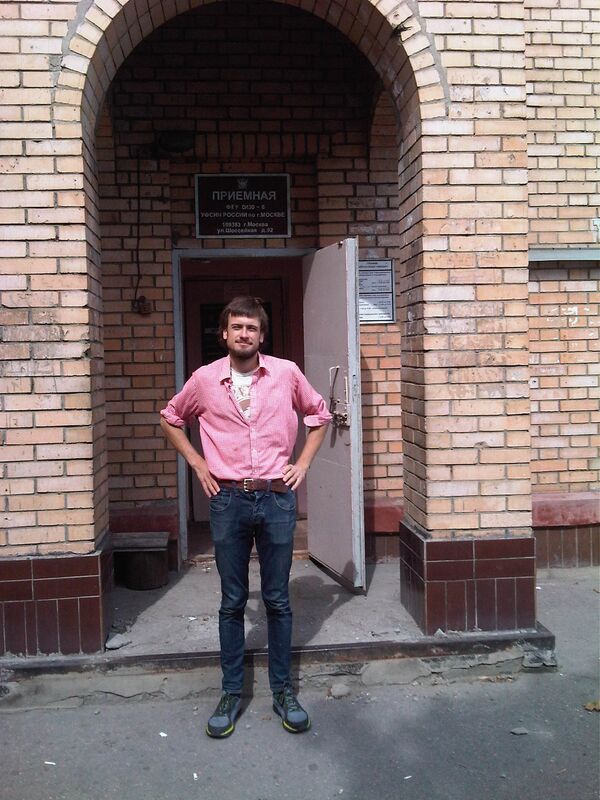

Verzilov then clambers out of the beat-up vehicle and heads towards the southeast Moscow prison for a meeting with his wife, the now world-famous Siberian who has rapidly become a poster girl for would-be revolutionaries the world over.

A few minutes later, he emerges despondent. The prison authorities have decided to cancel the meeting. “They said to come back at 7 a.m. tomorrow,” he shrugs.

Tolokonnikova, 22, and fellow group members, Maria Alyokhina, 24, and Yekaterina Samutsevich, 30, were jailed on August 17 over a “punk prayer” in Moscow’s largest cathedral in a trial that attracted both mass media attention and sharp international criticism.

An edited clip of the protest posted online showed the group alternately high-kicking and crossing themselves at the altar of the Christ the Savior Cathedral, the accompanying “Holy S**t” song urging the Virgin Mary to “drive out” President Vladimir Putin and railing against the powerful Orthodox Church’s pre-election support for the former KGB officer.

The group members were charged with “hooliganism,” the oddly antiquated term masking the judicial gravity of an offence that carries a maximum of seven years behind bars. Jailing the women for two years, the judge said they had “deeply insulted Orthodox believers” and only a custodial sentence could “correct” them.

As the Pussy Riot story made global headlines, Verzilov’s fluent English and media skills quickly saw him become the de facto spokesperson for the band and he has been a staple on international news channels in recent weeks.

“They say the Kremlin spent millions of dollars trying to put across a positive image of Putin’s Russia in the West,” he laughs as the taxi crawls back the way it came through the mid-afternoon Moscow traffic. “But the adverse publicity from the Pussy Riot case means all that money was wasted.”

Verzilov, a wiry 25-year-old with an unkempt beard and a predilection for pink shirts, is clearly relishing the group’s moment in the spotlight and the chance it gives him to put across their message of non-compliance with federal authorities they see as both corrupt and illegitimate. So much so, he says, that the group would have gone ahead with their “punk prayer” in Moscow’s Christ the Savior Cathedral even if they had known the consequences beforehand.

“That’s the price you have to pay,” he insists. “And the only thing we are afraid of is that our struggle will take a long time – that it could take some 15 years or so to see real change in Russia.”

Pussy Riot – Media Machine

But Verzilov admits that while international media have focused almost obsessively on the Pussy Riot case, they have failed to pick up on other concerns voiced by Russia’s opposition.

Britain’s The Guardian newspaper has published more than fifty articles on the photogenic group since their February protest, but has not made a single mention of the case of Taisiya Osipova, the overweight 28-year-old wife of an opposition activist sentenced to ten years in jail late last year over the possession of hard drugs.

Supporters of Osipova, who like two of the Pussy Riot members is the mother of a small child, allege she was framed after refusing to provide police with information on her husband. Her sentence was dubbed “unnecessarily harsh” by Dmitry Medvedev, who also called for a new probe into the case, before he handed over the presidency to Putin this May. But Osipova remains behind bars, despite a court overturning her sentence earlier this year.

“In cases like that of Osipova and the people detained at the May 6 [anti-Putin] riots in Moscow, it’s hard for people outside of Russia to understand what’s going on,” Verzilov says. “But the Pussy Riot story and the court case is very easy to understand for the West. Pussy Riot is basically a machine placed inside the media.”

“No one is denying a Western influence,” he goes on. “Pussy Riot as a band was modeled on things which were at the forefront of Western culture in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. And after their protest was crushed, it was very easy for the West to get this as an illustration of what is happening in Russia.”

‘Vengeful’ Putin

For a group whose last three songs have had Putin in the title, it’s clear that Pussy Riot have something personal against the Kremlin strongman.

“For Pussy Riot, the figure of Putin is a sexist, macho character who glues Russian politics together,” Verzilov says.

And he has no doubt that Putin personally ordered the jailing of his wife and her fellow band members.

“Putin doesn’t like to forgive his enemies,” he says. “It’s clear that he is a vengeful man.”

Putin said ahead of the verdict that he hoped the court would not judge the women “too harshly,” in comments that triggered a wide range of interpretations.

“Our sources say he was really annoyed by the [December 2011] Red Square protest, when Pussy Riot sang ‘Putin’s pi**ed himself,'” he says. “They didn’t jail the girls then because this would have been too much even for Putin’s Russia. There would have been no one who would have supported that.”

“But I don’t think Putin realized, even in his wildest dreams, that [German Chancellor] Angela Merkel would be making statements or that British Prime Minister David Cameron would be asking him about some punk band,” he smiles.

Western Support

One of the most surreal aspects of the Pussy Riot trial was the spectacle of a radical, revolutionary art group being supported by the West’s political establishment, as the White House and Merkel lined up to condemn the “disproportionate” sentences.

And Verzilov admits that the situation caused him a certain amount of discomfort.

“Obviously support from Western officials and political institutions is a very different story from support from cultural figures, who are represented by their art. With governments it’s a more complex story,” he says.

“But when the White House speaks in support of Pussy Riot, we accept that as a statement of support, because, well, the U.S. does do some positive things for global democracy, as well as some horrible things against democracy in the world.”

Verzilov dismisses however suggestions that world celebrities such as ex-Beatle Paul McCartney and U.S. pop diva Madonna, who both issued public statements of support for Pussy Riot ahead of the verdict, were unqualified to comment on a Russian legal case.

“Look, you don’t need to know a lot about Saudi Arabia to understand that young women are getting stoned there,” he says. “It’s the same for Pussy Riot – you don’t really need to know a lot of things about Russia to know that young mothers are getting sent to prison after singing a protest song in a church.”

He also draws analogies between the Pussy Riot trial and the campaign by U.S. right-wing Christian fundamentalists against Madonna over her controversial 1989 Like a Prayer album and the storm that broke out in the United States over John Lennon’s 1966 quip that The Beatles had become “more popular than Jesus.”

“Things like this do happen in the West,” he says. “But they don’t lead to prison sentences. So people can easily make the comparison and see what’s happening in Putin’s Russia today.”

Guerilla Art

Although the Pussy Riot case may have thrust them into the international spotlight, Verzilov and Tolokonnikova had been making the news in Russia since the founding of the Voina guerilla art group in 2007, which is now split into two rival factions. He and a then heavily pregnant Tolokonnikova gained nationwide notoriety in May 2008 when, alongside other activists, they fornicated on camera in a protest called “f**ck for the bear cub-successor” in a Moscow museum on the eve of Dmitry Medvedev’s inauguration as president. The sexual protest took its name from Medvedev’s surname, which comes from the Russian for “bear.”

“I don’t regret that at all,” he says. “And I don’t think our daughter will either. Do the children of Hollywood stars feel bad about erotic scenes that their parents take part in?”

Voina split acrimoniously in 2009 and the St. Petersburg faction of the group has accused Verzilov of being a police informer and “provocateur.” But Verzilov dismisses the allegations as “baseless and meaningless.”

“They’ve never provided any explanation for their accusations,” he insists.

Orthodox Hatred

While international free speech champions may have defended the group’s right to protest and a significant number of Orthodox believers expressed disquiet at the confinement of the women, Pussy Riot also provoked genuine hatred among many Russians.

A RIA Novosti spot poll of worshippers emerging from the Christ the Savior Cathedral a week ahead of the verdict in the trial revealed a deep-rooted loathing of the group and their “insulting” protest.

“Yeah, of course, Christ taught people to forgive their enemies, but those bit**es should be put away for life, all the same,” snapped Svetlana, a young Muscovite, as she stood on the steps of the cathedral.

And Verzilov echoes the group’s court statement that parts of the cathedral performance were an ethical mistake, expressing his sympathy for “elderly believers” who may have been shocked by the sight of five young women in bright balaclavas dancing at the altar of the landmark cathedral.

“I’m really very sorry for those people,” he says. “But older people often mix conservative and traditionalist values. You know, Christianity is about forgiveness and love and the ability to find compassion for those who have insulted you.”

“And for some reason these people don’t seem to be insulted by Patriarch Kirill getting involved in politics,” he adds, a reference to the Orthodox Church head’s comment ahead of the March 4 presidential polls that Putin’s first two terms of office were a “miracle of God.”

He also suggests state-media coverage hardened the opinions of “people who prefer to get their information from federal television.”

“State run channels have run some really brutal coverage of Pussy Riot,” he says.

Canada

Russian state media has made much of Verzilov’s dual Russian-Canadian citizenship and Tolokonnikova’s Canadian permanent residence status, the latter cited during an April documentary on federal television as proof of her “close links with a foreign government.”

The thinly-veiled accusation of Western support for the group echoed Putin’s allegation late last year that the United States was backing unprecedented opposition protests against his rule.

But although a smirking Tolokonnikova told state television that she did not possess permanent residence status in Canada, Verzilov confirms the existence of her residency card, a copy of which was shown on air during the documentary.

“I don’t think she took that state TV presenter too seriously,” he says.

The Future

Pussy Riot’s lawyers plan to appeal against the sentence next week. And after an Orthodox spokesperson said following the verdict that it hoped the authorities would show mercy, hope rose among the group’s supporters that they could soon be released.

But Verzilov says that if the appeal fails, the group will not appeal for a presidential pardon.

“Nadya says ‘let Putin ask us for forgiveness,’” he says, using the familiar form of his wife’s name.

Tolokonnikova, Alyokhina and Samutsevich are due to be moved to separate penal colonies in the next two weeks to start serving the 14 months they have left to serve. (Time spent in pre-trial detention centers counts for double under Russian law.)

“It’s been leaked that Nadya will be sent to [the central Russian region of] Mordovia,” Verzilov says.

But despite fears expressed by Pussy Riot lawyer Nikolai Polozov that his clients could face physical danger in a far-off penal colony, Verzilov is surprisingly calm about his wife’s safety.

“Nadya is quite charismatic and good at talking to people,” he says. “She says that while there have been some negative attitudes in prison, after two or three hours of conversation, most people change their minds.”

“The authorities are very worried about this,” he adds. “Given the present attention, if anything happened to them, this would see a massive reaction, so they will be very careful.”