A bottle of vodka and some contemporary Russian literature were the two things Malian politician Moustapha Dicko asked for from Moscow.

He paid little attention to the smooth bottle when presented with it in Mali’s capital, Bamako, but closely examined the books, a short-story collection by a firebrand leftist and a Buddhism-flavored satire of the information age.

Small wonder: Despite his day job as a senior member of a major political party, Dicko is also a university instructor with a PhD dissertation on early Tolstoy under his belt.

“I quit drinking and smoking two decades ago,” Dicko said, speaking in flawless, nuanced Russian – though he conceded with a smile that the alcohol consumed in the 1980s when he was a postgraduate student in then Leningrad probably helped him master the language. (The bottle brought specially from afar, in true Russian form, would be a treat for his friends and guests.)

People like Dicko are to be found everywhere in Mali.

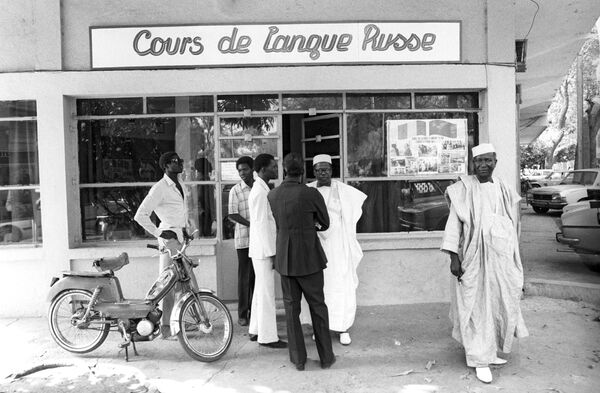

Among European nations, only France, the former colonial power, appears to rival Russia in terms of brand recognition in the West African country, which became a zone of Soviet interest after gaining independence in 1960.

For decades, the Soviet Union trained Mali’s officials and intelligentsia, developing local infrastructure and mapping the country’s abundant natural resources.

“We have had very close ties to Mali throughout recent history,” said Evgueni Korendyasov, Russia’s ambassador to Mali in 1997-2001, who now conducts research at the Center for Russian-African Relations at the Russian Academy of Sciences.

But ties have been all but severed in the post-Soviet period, with modern Russia unaware of the foothold it still has in Mali – and the window of opportunity for rebuilding those ties is shrinking.

Anti-Capitalist Friendship

Ideologically, involvement with Mali and other African countries that became independent in the 1960s was part of the Soviet Union’s anti-capitalist struggle. More pragmatically, it also filled the vacuum of geopolitical influence left after the break-up of the colonial system.

Whatever the motives, the Soviets spared no effort. Though overall financial estimates of Soviet aid received by Mali are hard to come by, Moscow’s involvement with the country was all-encompassing, Korendyasov said.

The Soviet Union built hospitals, stadiums and administrative offices, helped develop Mali’s gold mining industry, conducted exhaustive geological exploration of its natural resources and constructed the country’s sole concrete plant. The Malian army still uses Soviet-made APCs, fighter jets and helicopters.

Between 1960 and 2013, about 10,000 Malians graduated from Soviet and Russian colleges and universities, said Oleg Fedotov, an attaché of the Russian Embassy in Bamako.

Though encompassing only a fraction of Mali’s population of 14.5 million, the education program had a strong impact: Mali had no institutions of higher learning in Soviet times – the University of Bamako opened only in 1996 – which gave a career edge to Soviet-educated graduates.

The current, interim president of Mali, Dioncounda Traore, is a graduate of Moscow State University’s prestigious Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics. His predecessor, Amadou Toumani Toure, ousted in a coup last year, studied at an elite paratrooper school in Ryazan, 200 kilometers southeast of Moscow.

Even a lawmaker from the nomadic Tuareg people interviewed by RIA Novosti in Bamako recalled with a fond smile the time he spent at a Communist Party school in Moscow in the late 1960s.

The geopolitical wooing had mixed results: Though it embraced Communism for a while in the 1960s, Mali later joined the Non-Aligned Movement and maintained an ideological distance from both the Soviet Union and the West.

But Moscow never abandoned its involvement with Mali, even though the relationship remained economically one-sided.

In a telling example, cargo holds on the direct Moscow-Bamako flight (now defunct) usually carried countless Soviet-made fridges, which Malian students had the right to buy upon graduating and stuffed full of belongings they had accumulated while in the Soviet Union before heading back home, Fedotov said.

Terra Incognita Again

Before 1991, Russia had separate trade and military missions, as well as a cultural center and a press center, in Bamako. Now all that’s left is the embassy, though the cultural center is due to reopen in 2015.

“In the 1990s, we stopped providing unilateral aid and switched to a quid pro quo relationship, which was less attractive for Mali,” Fedotov said.

Moreover, Russia’s diplomatic focus moved first to the West, then to Asia and the other three BRIC countries – Brazil, India and China – and away from sub-Saharan Africa, the diplomat said.

Russia is still accepting Malian students – the Russian government is funding 20 grants a year compared to 300 in Soviet times – and training the country’s policemen, soldiers and peacekeepers. Indeed, several young pilots encountered by RIA Novosti at the Malian Air Force base in Sevare spoke Russian, many of them freshly back from a training facility in the Russian city of Syzran, with pictures of snow and fur hats to show for it.

But there are only 135 registered Russian citizens currently living in Mali, most of them women who married Malians or children from such marriages, Fedotov said. Russians visiting Mali on business can be counted on one hand, he added.

Russian companies are slowly penetrating African markets – LUKoil is working in Nigeria, steel giant Severstal in Guinea and its daughter company Nord Gold in Burkina-Faso, among others – but they are largely absent from Mali.

Neither Russia’s Foreign Ministry nor its Federal Customs Service has statistics for bilateral trade turnover with Mali.

The state-controlled daily newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta said last year, citing unspecified Russian army sources, that the Malian military is spending “tens of millions of dollars” a year on Russian military equipment. But equipment maintenance is handled by Ukrainian companies, not Russian ones, Malian Air Force Colonel Abdoulaye Diallo told RIA Novosti.

Theoretically, investment opportunities are plentiful: The country is a major cotton producer and mines 50 to 60 tons of gold a year – though it has no gold refinery – not to mention the largely untapped deposits of oil, gas, iron, bauxite and uranium.

Part of the problem is Mali’s landlocked location and lack of transport infrastructure, especially in the desert where most resources are concentrated, Fedotov said. Corruption also complicates investment: Mali ended up 105th of 174 countries in the 2012 Corruption Perception Index by Transparency International. (Russia was 133rd.)

“But the real problem is that nobody in Russia knows about Mali,” Fedotov said.

“The level of activity we’re showing [in Mali] corresponds to the level of our interests, both strategic and tactical. You can’t run faster than your pants allow,” ex-ambassador Korendyasov said.

Meanwhile, other countries are boosting their economic presence in Mali. Algerian companies obtained permits to mine for various resources in the north, though plans were mothballed after the separatist uprising broke out there in 2012; Libyans control most of the hotel industry; and China, ubiquitous in Africa, is swamping local markets with consumer goods.

All major players have to go to great lengths to curry favor with Mali’s officials and ordinary people: Libya, for example, constructed an entire district of government buildings in Bamako, and the Chinese erected a new bridge across the Niger – both projects free of charge.

Russia is far ahead of the game in terms of laying groundwork – but fails to capitalize on it.

And time is running out: As Soviet-educated elites reach retirement age, the new generation of Malian leaders and officials may not be as amenable to cooperation with Russia.

The younger pilots at the Air Force base in Sevare, for example, trained in both Russia and the United States. Captain Amadou Sanogo, who staged the 2012 coup – at the age of 39 or 40, accounts differ – and remains at the head of an informal junta accused of still pulling strings in the country, also trained in America (which denounced the coup), not in Syzran.

“We have 10, maybe 20 years to act,” Korendyasov, the former ambassador, said. “Then we'll have to deal with a new generation of Malians who have no ties to Russia.”