KABUL, June 6 (Alexey Eremenko, RIA Novosti) – The show by Afghan alt rockers Kabul Dreams kicked off and wrapped like a school band performance: A teacher welcomed the trio onstage at the auditorium of Kabul’s Lycee Esteqlal and gave them flowers afterward, as some 200 spectators cheered in their seats.

But in-between, the band sounded perfectly grown-up, with enough crunchy guitar, solid hooks and strobe lights to have the audience whistling and howling like veteran rock fans anywhere between Berlin and San Francisco – and head-banging by the stage during the April show’s encore.

Kabul Dreams are often called the first rock band in Afghanistan – about the last country associated with a thriving rock scene. And though they weren’t the first, they are undisputed trailblazers for the local Western-style music scene, which has come a long way since the ouster of the anti-music Taliban regime in 2001, and is doggedly carving a niche for itself next to thriving homegrown pop stars.

Though Afghan bands are still miles away from packing stadiums, the prerequisites for a burgeoning rock scene are falling into place: The country’s population is young, rapidly urbanizing and keen on modern communications and media, which have improved vastly over the past decade.

Kabul’s Nirvana

In the 1970s, Afghanistan saw a slowly budding rock scene, with groups like The Stars and The Four Brothers. But none left any records, and the scene was swept away by the three decades of war that began in 1979 with the Soviet invasion.

Now, there are a dozen rock bands in Kabul alone, and that’s not counting hip hop and electronica performers, according to Travis Beard, the Australia-born founder of a fledgling arts festival here, and one of the foreigners who’s been whetting Afghans’ appetite for modern Western music.

This spring Kabul Dreams were a major attraction – though not a headliner – at Beard’s Sound Central festival, now in its third year. Sponsored by a handful of Western embassies, it ran for four days in late April/early May and featured an extensive lineup of musicians, an arts program including local graffiti artists and a special “women day.”

The band was born in 2008, formed by three Kabul residents, and became the first rock band in the Afghan capital, but not the first in the country. That title – among bands that are still active – goes to Herat-based, ’60s-inspired blues/folk collective Morcha, founded in 2005.

Kabul Dreams’ tour circuit doesn’t scream cosmopolitan – they have played India, Uzbekistan and Estonia – but their debut album “Plastic Words,” which came out April 23 bearing traces of Nirvana and Placebo, was mixed by Grammy winner Alan Sanderson, who has worked with Michael Jackson, Counting Crows and Weezer.

So the Western influence on Afghanistan’s music scene seeps in from many directions.

The Mohawk-sporting, outspoken Beard – who first landed in the country as a journalist and got bitten by the Afghanistan bug, as he says – has been organizing music events there since 2010, produces a doom metal band called District Unknown and plays punk-tinged rock in a trio called White City with two other Western expats in Kabul.

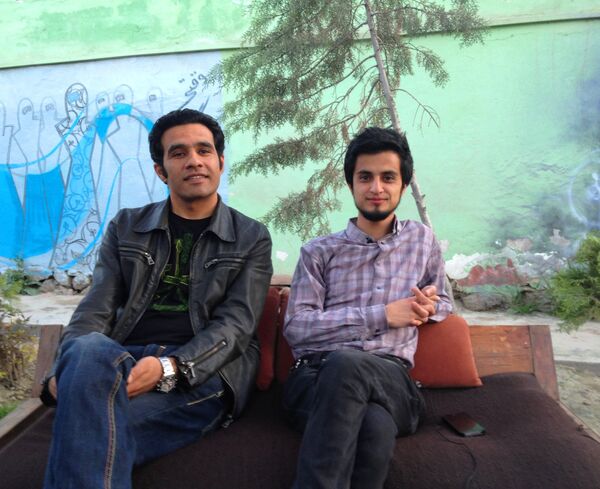

The capital also has a music school and a recording studio, opened in 2011 by Afghan-born Humayun Zadran and American Robin Ryczek at The Venue – a café that looks like any Western bohemian hangout, with cozy seats and graffiti on the garden walls, though without alcohol and tucked behind the obligatory outer wall of dull concrete, thick enough to (hopefully) stop bullets.

The place does not lack for students, who are interested in all kinds of music from folk to metal, according to Zadran.

The Cities Listen

The Afghan diaspora, as well as neighboring Central Asian countries with relatively laxer cultural policies, are important target audiences for Western-style Afghan musicians, said Sharifi of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies.

About 300,000 ethnic Afghans live in the United States, according to the Afghan Embassy in Washington. Another 200,000 reside across Europe, according to Afghan refugee network FAROE.

But the domestic market is not to be underestimated, Sharifi said.

Though no estimates of this market are readily available, a few other statistics serve as interesting proxy measures.

One is Afghanistan’s urban population, which has grown between 2002 and 2010 at an annual rate of 5.5 percent, reaching 8.5 million of a total population of 34 million, according to World Bank data. And a far greater number of people have livelihoods that depend on cities – up from 15 to almost 50 percent in the decade since the Taliban's ouster, according to Sharifi. The trend leads to greater exposure to Western culture, previously unknown to many Afghans.

Afghanistan is also a very young nation: Though no national censuses have been held since 1979, the median age in 2010 was 16.6 years, according to the UN Population Division – compared to 37.9 in Russia and 36.9 in the United States.

Furthermore, the country’s media and communications technologies are evolving rapidly. There are 36 nationwide television channels, according to Kamal Nabizada, owner of local Arezo TV; and up to 16 million Afghans use cellphones.

All of this makes up for a large potential market for people with electric guitars, and demand is definitely present, all those interviewed for this article agreed.

Afghan rock bands sell very well, Sharifi said, adding “there’s a business going on, both for the Afghans and the diaspora and Central Asia.”

But anecdotal evidence suggests the market isn’t exactly the hope of the Afghan economy just yet. Turnout at the Sound Central festival did not exceed 600 a day, with tickets costing $5, Beard said.

Attendance is similar at Kabul Dreams’ shows, with the price of admission around 250 Afghani, or $5. The sum is not that small, given that 36 percent of the country's population earns less than 1,250 Afghani a month, which is the official poverty line, according to figures from Afghanistan's Central Statistics Office cited in April by the US Department of State.

Afghans interested in Western culture and values, who are the prime audience for rock, hip-hop and electronica, are only a fraction of Afghanistan’s immensely complex, multilayered society, said Dmitry Alexandrov, an expert on Central Asia with the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies.

But he said that such a social group exists, unlike a decade ago, when exposure to Western culture in Afghanistan was negligible.

Can’t Stop the Music

Banning music was among the Taliban’s main claims to global notoriety in the mid-1990s, but the situation was less dramatic than many thought.

For one thing, the ban was not universal: Religious chants and some drumming at weddings were permitted. For another, it lasted only a few years and, in practice, was not the blanket ban the fundamentalists envisioned.

“Afghanistan is not more of a religious country, it’s more of a traditional country. And in our tradition, music is really important,” said Kabul Dreams’ bass player Siddique Ahmed.

“We have music going on in weddings, in houses, on weekends, at nights [when] people sit and read poetry and do music at home,” Ahmed said. “Even when music was banned, it really wasn’t, because people were still doing it and listening to it.”

Afghanistan’s indigenous music scene thrived post-2001. The country has a number of pop stars, like crooner Farhad Darya – who debuted solo in 1980 and remains ultra-popular – and the reality show Afghan Star, modeled on American Idol, is now in its eighth season and still a hit.

Even after the Taliban’s ouster, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan remains a culturally conservative country. But none of the musicians interviewed by RIA Novosti reported any serious trouble over their love of Western music and the lifestyle that comes with it, including hipster fashion and long hair.

“I don’t think we’re a priority,” Beard said.

Mohammad Shoaib, the guitarist of District Unknown, the doom metal band, who wears his hair down to his shoulders, said that sometimes older people in the streets tell him “you look like your sister,” but in a bemused, not hostile way.

His own father, a farmer, takes no interest in District Unknown, but neither does he make any move to ban his son from plying his metal wares, Shoaib said.

The members of Kabul Dreams describe their families as educated, and so the only worry their parents have is whether their kids will be able to pay the bills with their music – not unlike garage rockers’ families in the West.

As for the band’s audience, “they may not have any idea about rock music, but they enjoy it,” Qardash of Kabul Dreams said. “They see crowd, they see lights and live music and go okay, maybe this is what I want.”

“We had a few [critical] comments in the beginning,” he conceded. “But I know some of those people who made that kind of comment, and now they’re really into this kind of music.”

(This article has been amended to fix Sound Central's title, attendance and ticket price.)