WASHINGTON, June 11 (By Carl Schreck for RIA Novosti) – For decades Jim Patterson was arguably the most famous black man in the Soviet Union, a debonair homegrown poet whose childhood role in an iconic film cemented his celebrity and who later roamed the vast country reading his work to adoring audiences.

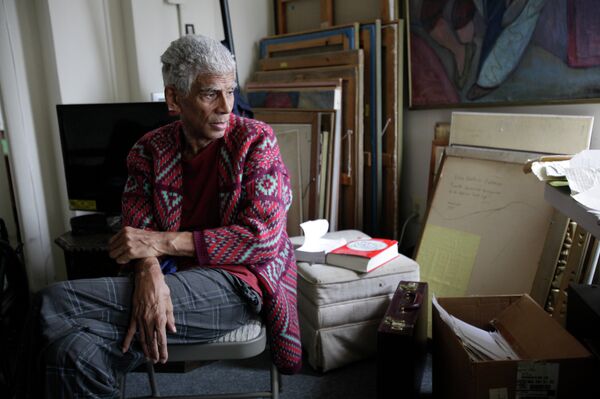

These days Patterson, whose African-American father emigrated to the Soviet Union in 1932, is convalescing in a threadbare subsidized apartment in downtown Washington, where he has led a reclusive life plagued by illness and depression since his Russian mother died more than a decade ago.

“I never wanted to leave forever,” Patterson, who arrived in America with his mother in the mid-1990s amid the economic turmoil in Russia following the Soviet collapse, told RIA Novosti in recent interviews. “I came here because it is my father’s homeland. It was not meant to be one of those cases where a person leaves for good.”

Patterson, frail from the effects of a blood infection that left him hospitalized for more than a year, remains largely bed-ridden though his legs are strong enough to withstand a few cautious steps. He is under the care of a Cameroonian nurse who administers his medicine and prepares his meals, including his beloved bliny, or traditional Russian pancakes, which he eats with an occasional dollop of sour cream despite doctors’ orders.

“I always say that I can’t get better without sour cream,” said Patterson, who speaks halting English and who spoke his native Russian in the interviews.

The faint timbre of Patterson’s voice is occasionally overwhelmed by the sound of jackhammers from a construction site across the street blaring through the open windows on his fourth-floor apartment, and his conversation is occasionally interrupted by a deep, hoarse cough.

Delving into his days in the world of the Soviet intelligentsia, however, has an obvious invigorating effect on him. He peppers his conversation with laughter, mischievous smiles and bursts of gesticulation with his bony hands, revealing a man clearly accustomed to performing before an audience.

The unruly mane of his younger years has yielded to a tighter silver coiffure, and though he occasionally struggles with dates, his mind remains sharp.

Patterson, who published several books of poetry during Soviet times and was a member of the Soviet Writers Union, dropped off the radar after his mother died in 2001, friends and loved ones say. Until recently he only maintained contact only with his brother in Moscow, relatives from his father’s side of the family in the United States, and a handful of friends.

Patterson’s ex-wife, Irina, said that until recently she believed he was dead after Russian journalists told her several years ago that he had drunk himself to death in Washington.

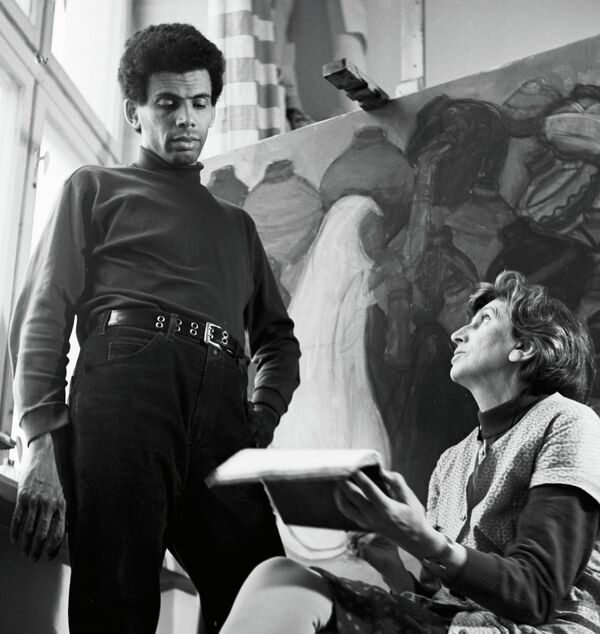

In reality, he had severed ties to his previous life as he dealt with the death of his mother, Soviet artist and designer Vera Aralova, though he continued to write poetry in both Russian and English while contemplating what to do with her paintings, Patterson told RIA Novosti.

“I just had no interest in talking to anyone,” he said. “That was my state of mind. I had turned completely inward, and that’s probably why I got sick. I wasn’t eating anything. I didn’t go anywhere.”

Several paintings by Patterson’s mother adorn the walls of his apartment. Dozens of others are stacked against the wall. Sheets of paper covered with scribblings are strewn about his desk, obscuring English dictionaries and books by Russian poets like Andrei Voznesensky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko – as well as his own books.

Hanging on the door handle is a small flag stenciled with the visage of another Russian poet with African ancestry, albeit one with more name recognition: Alexander Pushkin.

“I wouldn’t be who I am without him,” Patterson said.

‘Circus’ Star

James Lloydovich Patterson’s story begins in 1932, when his father, Lloyd Patterson, traveled to the Soviet Union along with several other black Americans, including poet Langston Hughes, in order to shoot a propaganda film called “Black and White” that was intended to highlight the evils of racism in the United States.

The film was never produced, but Lloyd Patterson decided not to return to the United States and went on to marry Aralova, a gregarious theater designer and painter who also went on to design women’s footwear that made waves from Warsaw to Paris.

The couple’s first son, Jim, was born in 1933, and three years later the boy was known across the Soviet Union for his role in one of the most famous scenes in the history of Soviet cinema.

“The Circus,” a musical comedy and melodrama about a white American circus performer and her illegitimate black son who find racial harmony and acceptance in the Soviet Union, became an immediate smash hit when it was released in 1936.

Jim Patterson was cast as the illegitimate son who in the final scene of the movie is passed around by audience members representing the Soviet Union’s numerous nationalities as they serenade him, in their respective native languages, with one of the country’s most famous ballads: “Song of the Motherland.”

The film was adored by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and became “a touchstone moment in the Soviet cultural psyche,” said Anna Katsnelson, an expert on the Soviet cinema at Princeton University.

“The film was a monster hit known by all,” Katsnelson told RIA Novosti.

Patterson’s mother was played by the star of the film, Stalin favorite Lyubov Orlova, whose celebrity in the Soviet Union was comparable to that of Marlene Dietrich and Mary Pickford in Hollywood, Katsnelson said.

Orlova was married to the film’s director, Grigory Alexandrov, and the couple remained close to the Pattersons for the rest of their lives. Jim Patterson and his mother were regular guests at the couple’s dacha in the Vnukovo district in western Moscow, where Patterson said his family rented a nearby dacha.

Orlova, who had no children of her own, would often call Jim Patterson her son, and in interviews with RIA Novosti, Patterson several times referred to the actress as his “movie mom.”

Patterson’s star turn as a toddler would follow him his entire life, and his fond memories of his life in Russia remain inextricably linked to “The Circus.”

“I love Russia very much,” he said. “People were always very kind to me there. Maybe it was because of this film, but nonetheless it was nice.”

‘Stalin Pointed at Me’

In the years between the release of “The Circus” and the beginning of World War II, Patterson lived with his family in an apartment building populated by foreigners in central Moscow, some of whom disappeared during the Stalinist purges, he told RIA Novosti.

After Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, Patterson was relocated to Siberia along with his mother and two younger brothers, while his father continued to work as an English-language radio announcer in Moscow as German bombs fell on the Soviet capital.

Lloyd Patterson suffered a contusion that same year after a bomb was dropped in Central Moscow. Jim Patterson noticed a change in his father when he visited his family in the city of Sverdlovsk, where the family was living after their evacuation from Moscow.

“When he came and visited, he was experiencing some lightheadedness. I understand now what he felt like. It’s kind of the way I feel right now,” Patterson said.

Lloyd Patterson relocated to Komsomolsk-on-Amur in Russia’s Far East where he continued to work as a translator and radio announcer. He lost consciousness while at work in 1942 and subsequently died in a military hospital at the age of 32, according to the official account of his death.

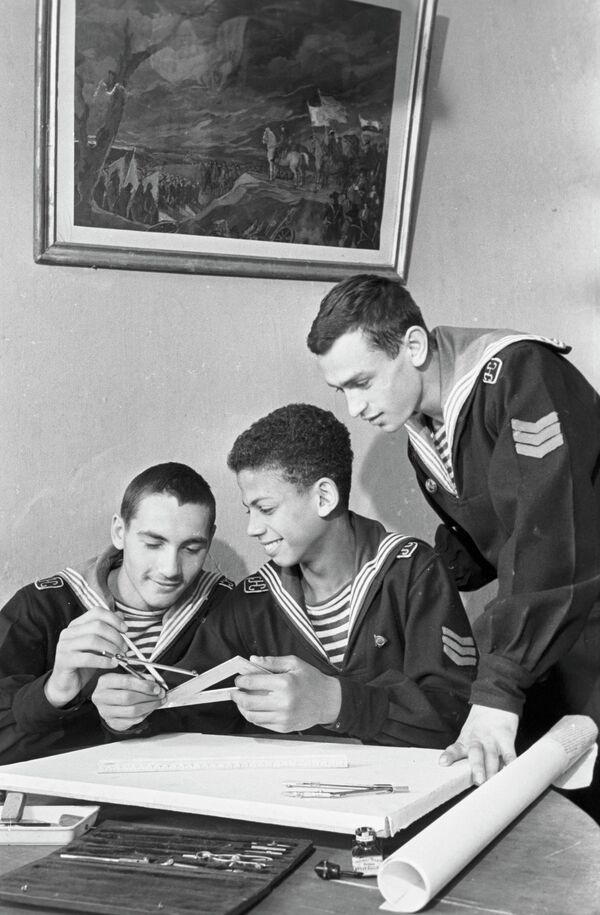

After the war, Jim Patterson enrolled at the Nakhimov Naval School in Riga and went on to become a Soviet naval officer serving on a submarine in the Black Sea. As a sailor with a highly unusual biography and skin tone for the Soviet Union, his naval service did not go unnoticed at the highest levels of the Soviet government.

During a Victory Day parade just a few years before Stalin’s death, Patterson marched passed Lenin’s mausoleum on Red Square with his fellow Nakhimov cadets and caught the eye of the Soviet leader.

“Stalin saw me, recognized me and pointed at me with his finger,” Patterson recalled. “ … He knew me from the film.”

About a decade later, Patterson was the subject of a secret letter sent by a Soviet Navy admiral directly to Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev. Citing the novelty of a black Soviet naval officer like Patterson – “a submariner, no less!” – the admiral proposed recruiting hundreds of other black men with relatives in the American South to train them to serve on Soviet ships as a propaganda weapon contrasting Soviet inclusiveness with endemic racism in the United States.

“Their letters to relatives and the global media will do all of the rest,” the admiral, Ivan Isakov, wrote in the 1959 letter to Khrushchev.

By the time the letter was sent to the Kremlin, Patterson had already demobilized and was pursuing a career as a poet, a dream he began cultivating while studying in Riga. Patterson told RIA Novosti that there were discussions among Soviet military and cultural officials about how best to utilize his talents and interests.

“One group said, ‘We want to make him an admiral,’” Patterson recalled. “And the writers said: ‘No, he’s closer to us. You can make an admiral out of anyone.’”

A Poet’s Life

After his demobilization from the Soviet Navy, Patterson embarked on a literary career under the tutelage of the highly respected Soviet poet Mikhail Svetlov, who helped him enroll in the Maxim Gorky Literary Institute and, ultimately, backed his membership in the Soviet Writers Union in 1967.

The themes of Patterson’s early work included his literary hero, Pushkin, as well as Africa, where he says he traveled as a tourist when he was “nobody” in the literary world. He told RIA Novosti that he still winces when he contemplates the quality of his early work, which he said mimicked Pushkin’s rhythmic patterns.

“I look back with horror at my early poems,” he said.

After joining the Soviet Writers Union, Patterson crisscrossed the country to read his poems before audiences, who greeted him warmly and constantly asked him to talk about his role in “The Circus.”

“All around the country they knew me as the boy who played in that film,” Patterson said. “That really helped me at that stage in my career.”

After a while, however, the questions about the film grew wearisome, he said.

“People meant well, of course, but at that time, as a man of letters, I really wanted to read my poems,” Patterson said.

Patterson’s poetry garnered positive reviews from Svetlov and other prominent Soviet poets, though his stature at home and abroad paled in comparison to many of the country’s poets at the time, both those who were embraced by the Soviet government and those who eventually landed in exile, such as Joseph Brodsky.

Mark Lipovetsky, a literary critic and a professor of Russian studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, told RIA Novosti that while he is not familiar with the bulk of Patterson’s work, his oeuvre includes poems that “gravitate to the liberal wing of the post-Stalin poetry” and are clearly influenced by Soviet poet Yaroslav Smelyakov and renowned bard Bulat Okudzhava.

Lipovetsky said that examples of Patterson’s poetry that he has read do not question the “Soviet mythology of the great past” in the way that “the best poets of his generation did.”

Patterson traveled throughout the Soviet Union performing his work until the late 1980s and published his last collection of poems, “Night Dragonflies,” in 1993, a little more than a year after the only country he had ever lived in collapsed.

Trials Abroad

Like many of their fellow compatriots, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the ensuing economic free-for-all hit Patterson and his family hard. The family still had their apartment in western Moscow and a dacha north of the city, though there was not much market demand for the poet’s work.

Patterson’s mother, Vera Aralova, was already in her 80s, and he says he made the decision to move her to the United States after visiting the country for the first time in 1989 as part of a Soviet delegation of artists and journalists with African-American heritage.

In late 1994 the poet and his mother moved to Washington, bringing with them several of Aralova’s paintings. Patterson married only once, in the late 1980s, but was divorced from his wife, Irina Tolokonnikova, when he made the move.

Tolokonnikova told RIA Novosti by telephone that she and her ex-husband exchanged a few emails after he left Russia but that she never heard from him after 1996.

Tolokonnikova and friends of the Pattersons in the United States said that Aralova never approved of the couple’s relationship, a familial dispute that was aired on Russian television last month.

Until they spoke via video linkup on the talk show, Tolokonnikova did not know that Patterson was alive, she told RIA Novosti.

After arriving in the United States, Patterson and his mother sold her paintings at exhibits in the Washington area and elsewhere on the US east coast over the next several years, earning just enough – together with social security checks – to keep their heads above water, he said. They were in touch with his father’s relatives and moved in the Soviet émigré community in the area as well.

Despite the lean years and his isolation after his mother’s death, Patterson told RIA Novosti he does not regret the move. It was the least he could do for his mother, he added.

“I was very happy that I found the opportunity to do something for my mother in the final years of her life,” he said, adding that he worked relentlessly writing poetry in English and Russian during his years of seclusion.

Patterson’s friends say they only learned years later that Aralova had died in 2001. Patterson, they say, simply disappeared.

“Jim didn’t call anyone,” Anna Toporovsky, a Baltimore-based radio journalist who befriended the family after they arrived in Washington, told RIA Novosti.

Patterson’s brother, Tom, took his mother’s remains back to Moscow, where she was interned in the Armenian Cemetery next to her third son, Lloyd Jr., who perished in a car accident in 1960.

Talk of this period has a visible deflating effect on Patterson, though he does not shy from the subject.

“I didn’t think that I needed to contact anyone else,” he said. “That’s what was difficult. I depended on myself and only on the help of my brother.”

Patterson said he essentially stopped eating and ignored his health completely. In early 2011, he collapsed while working at his desk. “I felt the life going out of me,” he said.

Fortunately, Patterson said, at that very moment a local social worker knocked on his door and called an ambulance.

He spent around 18 months, in the hospital before recuperating enough in 2012 to move back to the low-income apartment building where he now resides under in-home care.

Patterson, who turns 80 next month, said he still writes every day, including poems in “American slang” which he hopes to publish sometime soon. He declined to show the poems to a reporter, saying that as a professional poet he could not stomach giving them to someone in such rough form.

Tom Patterson, a retired television operator, told RIA Novosti by telephone from his dacha outside Moscow that he plans to travel to Washington to visit his brother later this year and return their mother’s paintings to Russia.

It’s a task that both brothers feel passionate about. Jim Patterson said that he and his mother never sold the originals they brought over from Russia – only copies that Aralova made stateside.

“I saved the originals,” he said. “And now I see I was absolutely right.”