WASHINGTON, June 19 (By Maria Young for RIA Novosti) – Nearly a dozen long-lost, rarely seen Soviet films and scores of screenplays that were never produced about the persecution of Jews during World War II have been revived to offer decades-old evidence of a side of the Holocaust few people recognize today.

From the dusty archives of Moscow and elsewhere across Russia, the works are featured in “The Phantom Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and Jewish Catastrophe,” a startling new book released by Rutgers University Press this week.

“Those films have been pretty much just erased from history, really,” said the book’s author Olga Gershenson, an associate professor of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, in an interview with RIA Novosti.

“If you think about the holocaust films in the US and Europe, people immediately think, ‘Oh, “Schindler’s List” or “Life Is Beautiful,”’ but basically half of all the Holocaust victims, nearly three million people, were murdered on the territory of the Soviet Union and it’s just not part of the popular public imagination. It’s just completely off the radar… people don’t think about what happened in the Soviet Union,” she added.

The grim history of millions that were killed in concentration camps and death camps in Germany and Poland is well-documented in historical films and books, but Gershenson said what happened in the Soviet territories was sometimes called the “Holocaust by bullets,” where Jewish people were simply executed on the spot.

Gershenson stumbled across the idea while writing a grant proposal, and realized an examination of Soviet Holocaust films “had never been done before.”

Part of her mission was debunking the myths and revealing the works that Soviet-era rulers tried to hide. As tensions and violence escalated across the region, the films – sometimes graphic and violent – were banned in the Soviet Union and screenplays that depicted the Jewish fate during World War II were denied permission for production.

Soviet Holocaust filmmakers were treated with cruelty said Gershenson, including the director and others who worked on the 1966 movie “Eastern Corridor,” set in Nazi-occupied Belarus.

“He pretty much paid with his career for this film, and his scriptwriter was told verbatim, ‘You will never have professional work,’ and he never had professional work again,” said Gershenson.

More famous is the story of “Commissar,” a film made by Aleksandr Askoldov in 1967 that was officially banned for its overt sympathy for Jews, and released in 1988.

“It was meant to be destroyed at the studio and the editor of the film, at night, carried out the film stock literally under her skirts. Askoldov met her at night and the box with the film stock with all the scenes sat under his bed for 20 years so it’s only thanks to this historic woman that we even have the full film,” said Gershenson.

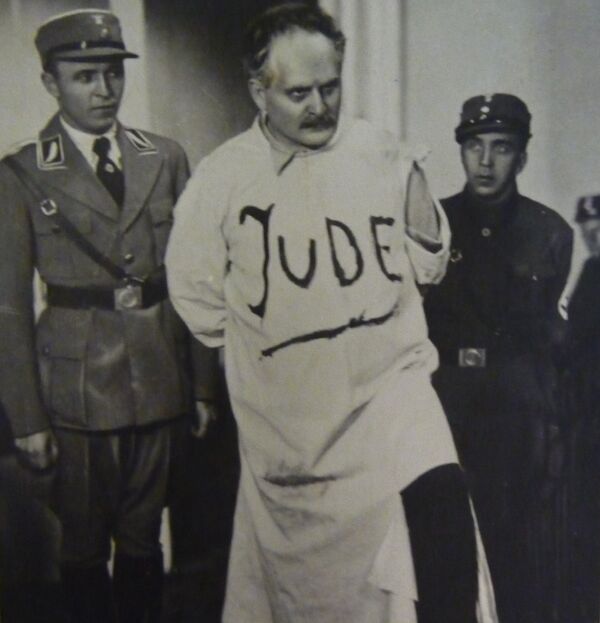

One of the first Soviet-made films to take on the topic of the Nazi persecution of Jews was “Professor Mamlock” in 1938. Written by Friedrich Wolf, a Jewish doctor and writer from Germany who came to Russia after the Nazis rose to power, it depicts the stark tale of a German-Jewish doctor who was taken by Nazi soldiers and marched to his death. It was shown briefly in Soviet theaters, but had been banned by the late-1940s, said Gershenson.

Over the course of several trips to Russia, where she was born, Gershenson searched through massive state archives of Russian history and records from the various committees charged with approving or rejecting film proposals to find films, scripts and screenplays, some with newer versions that had been altered under orders to delete Jewish characters.

All these years later, she said, most of the filmmakers still living are in their 80s and 90s now, had long given up hope of ever seeing the films made public, and were “overjoyed” to learn about her work.

It was important to set the record straight, she said, because “it goes to the core of not just contemporary Jewish identity but also their 20th century history.”

Gershenson said it was also important to recognize the sacrifice that went into making these works.

The filmmakers and screenwriters, she said, “are unsung heroes. It’s remarkable to try and make a film that you pretty much know will bring you nothing but trouble. They are heroes. Their professional life and sometimes their personal lives were destroyed for this, so I think we owe them their due.”