Last week Texas put to death Kimberley McCarthy, the 500th inmate to die since the state resumed carrying out executions in 1982. And once that was done, a data entry clerk in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice participated in a local tradition – he (or she) entered McCarthy’s last words into a database containing all the final statements of those who have died by the state’s lethal needle.

Although I’ve lived in Texas for years, I didn’t know the database existed until this week. I spent some time reading it Tuesday afternoon, and the experience was as somber as you’d expect. In our culture we like to record the last words of the famous, but most people slip away without saying anything memorable. Since we rarely know when we’re going to die, very few of us get an opportunity to compose a final statement. It’s a privilege that belongs mainly to the condemned, one of the few they enjoy, and not one that I envy.

McCarthy’s last words had nothing to do with her crime, which was heinous - the murder of an old lady for money to buy crack. Rather, she thanked some people and affirmed her religious faith:

“I just wanted to say thanks to all who have supported me over the years: Reverend Campbell, for my spiritual guidance; Aaron, the father of Darrian, my son; and Maurie, my attorney. Thank you everybody. This is not a loss, this is a win. You know where I am going. I am going home to be with Jesus. Keep the faith. I love ya'll. Thank you, Chaplain.”

Here McCarthy was in the mainstream of final statements: a few parting words to family and friends and a nod towards God. God, unsurprisingly, is a frequent visitor to the death chamber. Indeed, Charlie Brooks Jr., the first man to die in Texas’ modern era of executions (he kidnapped and murdered a car mechanic) converted to Islam in prison and left this world with a stream of Arabic and English dedicated to Allah.

No doubt it’s easier for the condemned if they have religious faith. God, Jesus, or Allah provide reassurance that life’s journey is not about to end on the executioner’s gurney, and that even the worst murderers will be forgiven in heaven as they were not forgiven by the State of Texas.

Protestations of innocence are common of course, while others try to extract something meaningful from the experience- to preach, even. This February, Carl Blue, who burned an ex-girlfriend to death, urged people to consider the reality of divine justice:

“Don't judge, I'm not judging. God has to judge those people. I forgive. Always remember, Romans 12:19 is for real, hell is for real.

If ya'll don't have your life right, get it right. We all have to die to get to heaven. Get your life right with Christ; it's coming to an end. I'm talking to each and every soul in this building, in this room. I don't hate nobody, you're doing what you think is your job.

God's law is above this law.”

And then he shifted to strange, country poetry:

Hang on. Cowboy up, I'm fixing to ride. Jesus is my ride.

Then he directed a few last words to his kids, the indirect victims of his crime, and added a bit more about Jesus.

The “cowboy” reference reminded me of some bizarre last words I read reported last year, when Jesse Joe Hernandez, who had beaten an 11 month old baby boy to death in 2001, cheered on his favorite football team as the drugs took effect: “Go Cowboys! Love ya'll man. Don't forget the T-ball!” His absolutely final words were: “I can taste it. Not bad.”

The condemned are, as a rule, very polite. It’s rare to see any expressions of defiance, or cursing. Some even go out of their way to be courteous in a way they, most likely, never were in life. Thus Ronald O’Bryan, who was executed in 1984 after poisoning his son with cyanide-laced Halloween candy, topped a remarkably even-tempered condemnation of the death penalty with a few words of thanks to the wardens:

P.S. During my time here, I have been treated well by all T.D.C. personnel.

…which I’m sure they appreciated.

So what would I say if I found myself strapped to the gurney, awaiting the jab of the needle?

I have no idea. It would probably depend on what I’d been accused of, and whether I was innocent or guilty. If the latter, I hope I’d have the guts to be honest about it, no matter how terrified I felt at the prospect of my execution. Even so, I doubt I’d have the self-discipline of those who say nothing at all, whether from fear or perhaps as a last act of defiance. Perhaps there’s something to be said for the approach of G.W. Green, executed in 1991 after killing a deputy sheriff.

“Let’s do it man. Lock and load. Ain’t life a (expletive deleted).”

Indeed it is.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and may not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

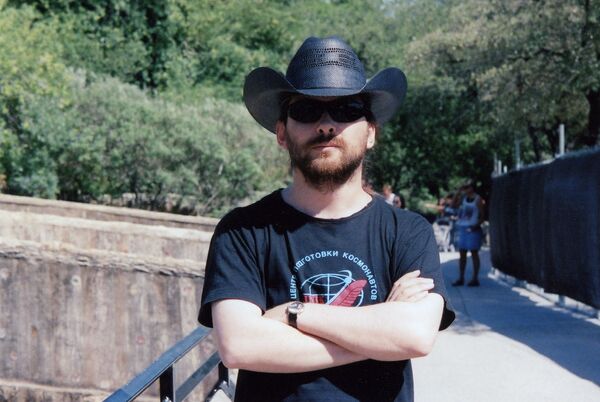

What does the world look like to a man stranded deep in the heart of Texas? Each week, Austin- based author Daniel Kalder writes about America, Russia and beyond from his position as an outsider inside the woefully - and willfully - misunderstood state he calls “the third cultural and economic center of the USA.”

Daniel Kalder is a Scotsman who lived in Russia for a decade before moving to Texas in 2006. He is the author of two books, Lost Cosmonaut (2006) and Strange Telescopes (2008), and writes for numerous publications including The Guardian, The Observer, The Times of London and The Spectator.

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Edward Snowden and the Irony of Leaking

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Istanbul and the Trouble With Opposition

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The Curious Russian Afterlife of Steven Seagal

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Is it Time for a Ladder on Everest?

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Bad Cars and Porn Stars, or a Few Words About Ladas

Transmissions from a Lone Star: A Cascade of Trouble: Life in Obama’s Second Term

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Printed Guns: Probably Not the Next Big Thing

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Why Dictators Should Be Wary of Certain Animals