WASHINGTON, July 26 (By Carl Schreck for RIA Novosti) – The charges against a handful of alleged criminals returned to Russia by the United States in recent years carry nothing like the political weight of those faced by fugitive former intelligence contractor Edward Snowden, even as US officials cite these deportations as they press Moscow to expel Snowden to face criminal charges at home, analysts said Friday.

Snowden “believes he essentially carried out a political act and is being persecuted for a political act,” Mark Galeotti, a transnational crime and Russia expert at New York University, told RIA Novosti.

“It’s up to Russia to decide if it accepts that. But it’s not as straightforward as finding some drug smuggler and putting him on a plane to end up in a Russian court.”

The US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) last month identified seven individuals returned by the United States to Russia in connection with criminal charges over the past five years, according to a report by the Pittsburgh Tribute-Review.

The United States and Russia do not have an extradition treaty, but US officials have said in recent weeks that the United States has returned 1,700 individuals to Russia over the past five years, more than 500 of which were removed in “criminal” deportations.

DHS did not respond to an inquiry Friday seeking the names and circumstances of other alleged or convicted criminals the United States has deported to Russia. But the individuals cited in the Tribune-Review report were sought by Moscow on charges such as larceny, fraud, robbery and embezzlement – felonies that Russia is unlikely to consider analogous to the charges of leaking classified information that Snowden faces in the United States, Galeotti said.

“These are very, very different cases,” he said.

This diplomatic disconnect was brought into sharp relief this week by Russian law enforcement officials who criticized Washington for shielding individuals Moscow considers serious criminals.

Russian Interior Ministry spokesman Andrei Pilipchuk on Monday cited as an example Ilyas Akhmadov, a former senior official in the Chechen rebel government that gained de-facto independence from Moscow following a brutal two-year war with Russian federal forces that ended in 1996.

Akhmadov fled Chechnya in 1999, shortly before the second Chechen conflict, which brought the region back under Moscow’s control, and secured political asylum in the United States in 2004. The decision sparked criticism at the time from Russian President Vladimir Putin, who said the United States had granted asylum to a “terrorist envoy.”

Meanwhile, senior Russian Prosecutor’s Office official Sergei Gorlenko this week accused the United States of refusing to hand over around 20 criminals to Russia over the past decade, including “murderers, robbers and corrupt officials.”

US officials have been hesitant to compare the Snowden impasse with other cases in the wake of the criticism from Russian officials this week. Instead they have continued to call on Moscow to act in line with broader cooperation between the two sides, including in the investigation of the deadly Boston Marathon bombing in April.

“We’ve been clear with the Russians that he is a US citizen wanted on very serious charges here, and he needs to be returned to the United States,” US State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf told a news briefing Thursday.

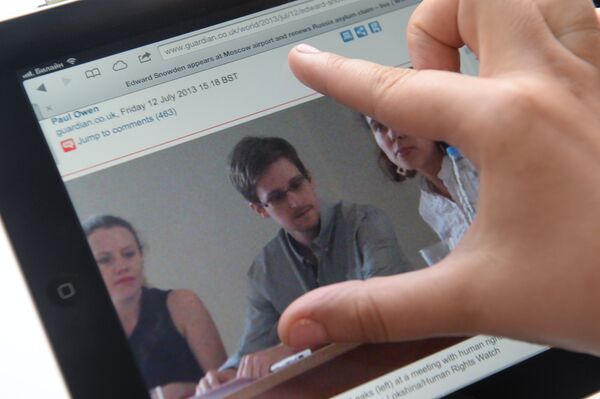

Snowden, who is wanted by the United States for leaking classified data about the US National Security Agency’s surveillance programs, formally requested temporary asylum in Russia on July 16.

He has reportedly been living at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport since arriving on a flight from Hong Kong on June 23.

Douglas McNabb, a Washington-based extradition lawyer, conceded that the individuals the United States handed over to Russia may not have been charged with “espionage or the super serious stuff.” But the fact that Washington has returned fugitives sought by Moscow is a logical basis for asking for Russia’s help in Snowden’s case, he said.

The United States can tell Russia that “‘we have given you people that you have wanted. This is a really important thing for us, and we want Snowden, and we would ask that you exercise your discretion and return him to us,’” McNabb said.

Given Washington’s reluctance to deport individuals like Akhmadov to Russia in cases the United States consider politically motivated, Russia’s apparent willingness to consider Snowden’s temporary asylum request is not surprising, Galeotti said.

“It doesn’t strike me as particularly strange if Russia likewise feels like it has the right not to send Snowden back,” he said.