The other day I read an interesting story: Apparently a recent investigation in Russia’s Far East has just resulted in Fyodor Dostoyevsky being cleared of instigating contempt of court. I’m sure that came as a great relief to the Russian writer, or at least would have if he hadn’t been dead for 132 years. His bones can rest easy, at least.

The details of course are all very strange, but in a nutshell: One man called another an idiot in court; an official then reported the name-caller for contempt of court; the offender then blamed his actions on the baleful influence of Dostoyevsky’s novel “The Idiot” and demanded its author be investigated.

Apparently Russian law demands that once a request has been made, the court must investigate – no matter how strange it seems. Hence a nine-month investigation into Dostoyevsky followed, which ended with the charges being dropped because the accused was 1) dead and 2) unable to influence anybody.

Now those are certainly good grounds for an acquittal. You might even argue that the whole thing was ludicrous and should never have gone to court. But was it so ludicrous? Who would deny that writers can have a pernicious influence upon readers? Lenin, Stalin and Mao all drew inspiration from books. Religious maniacs of every stripe are inspired by books. Books are dangerous; authors are not just boring people sitting in their underpants in front of a computer screen but deadly rebels to be feared and mistrusted.

Except…. it was Dostoyevsky – a dead man – who was on trial, and not his book.

But is it so strange to judge a man posthumously? After all, the concept of a posthumous pardon is widely accepted. Last month, the British government was reported to be considering granting a posthumous pardon to Alan Turing, the mathematician and World War II code breaker who was convicted of indecency under anti-homosexuality legislation in 1952. Turing was chemically castrated, and committed suicide two years later. A 2011 study meanwhile revealed that at least 106 people have been given posthumous pardons in US history, including 12 unfortunate souls who were executed.

Now it strikes me that a posthumous pardon isn’t much consolation once you’re dead. Certainly, I would prefer to receive any pardon I might be in line for before I go to the grave. But the idea of retroactive responsibility does not end there. A few years ago it was all the rage for European heads of state and church leaders to apologize for things their long-dead great-great-grandparents had done. You know: slavery, colonialism, that sort of thing.

Is that any stranger than taking the dead Dostoyevsky to court? Well, maybe there’s a difference. Posthumous pardons can at least ease the psychological suffering of the families and descendants of the wrongly condemned. I’m still skeptical about all those government apologies though. Call me cynical, but to me they sound like cost-free cant that fill the apologizer with a sense of unearned moral awesomeness, and that restore nothing to the people who suffered.

Anyway, I think what I’m getting at here is that we have a complex relationship with the dead. To some degree they are still with us, and the world in which we live is the world they helped make. I’m still not sure how much individual responsibility Dostoyevsky holds for that, though.

Anyway, I was thinking about this story, and then I remembered my university years in the early to mid-1990s. I studied English Literature, and the faculty was awash with people whose job it was to read Shakespeare and Jane Austen and identify thought crimes in the works of these long-dead individuals. It was very weird: These academics were always uncovering slavery or racism or sexism or anti-Semitism in books that were written hundreds of years ago when lots of people owned slaves and everybody was a racist and a sexist and an anti-Semite. Why, who could believe it? Elizabethans acted like Elizabethans! It was a completely fruitless and futile field of study, but these government-funded radicals nevertheless believed they were somehow striking a blow for freedom, or the liberation of the oppressed masses, or (yawn) whatever.

This was pretty much the norm in humanities faculties across the UK and US back then. I hear from folk younger than me that it still is, though I am so uninterested in that kind of “research” I can’t claim to have checked personally.

Still, that may be the closest experience I have had to the recent investigation into Dostoyevsky. There’s a difference though: Dostoyevsky was acquitted. Also, that story made me laugh. And since it was indeed a complete waste of time and resources and totally perverse, I’m pretty sure Dostoyevsky himself would have enjoyed it, were he still around. His books are full of dark irony and suffering human beings acting in baffling ways that defy logic, after all.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and may not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

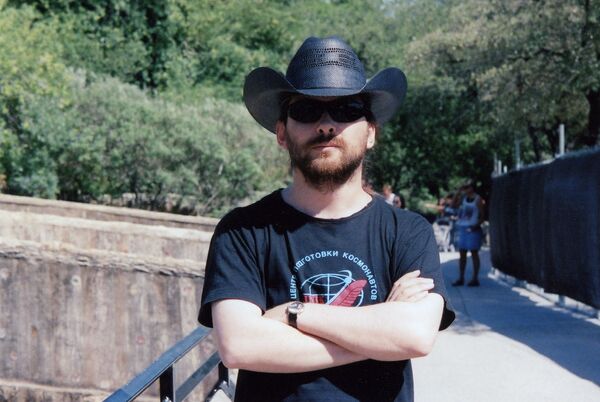

What does the world look like to a man stranded deep in the heart of Texas? Each week, Austin- based author Daniel Kalder writes about America, Russia and beyond from his position as an outsider inside the woefully - and willfully - misunderstood state he calls “the third cultural and economic center of the USA.”

Daniel Kalder is a Scotsman who lived in Russia for a decade before moving to Texas in 2006. He is the author of two books, Lost Cosmonaut (2006) and Strange Telescopes (2008), and writes for numerous publications including The Guardian, The Observer, The Times of London and The Spectator.

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The Reading Habits of Guantanamo Bay Inmates

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The Slow Creative Death of Vladimir Mayakovsky

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Why J-Lo Is More Ethical Than Our Greatest Statesmen

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Does Being a Rubbish President Invalidate Democracy?

Transmissions from a Lone Star: How Condemned Men (and Women) Say Goodbye

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Edward Snowden and the Irony of Leaking

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Istanbul and the Trouble With Opposition

Transmissions from a Lone Star: The Curious Russian Afterlife of Steven Seagal

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Is it Time for a Ladder on Everest?

Transmissions from a Lone Star: Bad Cars and Porn Stars, or a Few Words About Ladas