BENNINGTON, Vermont, August 14 (By Maria Young for RIA Novosti) – In this all-American town accustomed to its daily dose of sturdy New England fare, an unusual but enticing aroma drifts up Main Street, beckoning friends and strangers alike to the Crazy Russian Girls Bakery for a taste of a distant land.

“I like the stuffed things, the pierogies and things like that. I never had ‘em, and I like ‘em ,” said Keith Jelley, a regular customer who came in recently for his weekly “peasant lunch” with golubtsy (stuffed cabbage), potato-and-cheese pierogies (stuffed dumplings), kapusta (sauerkraut), and kielbasa (sausage), things many in this close-knit community had never heard of.

At this unique ethnic eatery, the locals come for the Russian food. And they stay for the Russian soul.

Soviet Influence

Nestled at the base of the Green Mountain range in southern Vermont, squeezed in between the colorful moose statues and quaint shops of Bennington, the bakery is testament to some of the darkest days of the Soviet era and a tribute to a beloved grandmother who found the grit to survive on her own, eventually coming to America with a deep love for her homeland still firmly intact.

“The struggle that my family had in Russia, really it made me who I am and made my children who they are and we bring that not only to the bakery but also to the community,” said co-owner and founder Natasha Garder Littrell, in an interview with RIA Novosti.

“My babushka, my grandmother, survived forced starvation, so anytime we came to her house in this country, the table would be collapsing with the weight of food. My grandmother always said, ‘You don’t know what it’s like to be hungry,’” she added.

The bakery began serving customers in 2009, serving some of the traditional foods handed down from ancestors of “untitled nobility” who lived in late-19th century Russia. Around that time, the carefully researched family history begins to read like something from a tension-filled, death-defying James Bond thriller.

Littrell’s great-grandfather, Vadim Leonidovich Bolychevtsev, became disillusioned with the government and joined the Bolshevik party shortly before the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

Leaving Russia

“He was exiled abroad for his activities by the Tsarist government, and on his return – after the revolution – he rose through the ranks of the party, eventually working directly under Beria, chief henchman under Stalin,” said Leonid Garder, Littrell’s father and the unofficial family historian, in an email to RIA Novosti.

“Upon a disagreement with Beria, Beria denounced him to Stalin, who issued a death warrant. Vadim was just able to escape,” he added.

Vadim’s daughter was Irina Vadimovna Bolychevtseva, who would eventually become Littrell’s babushka, and “she was one tough cookie,” Littrell said.

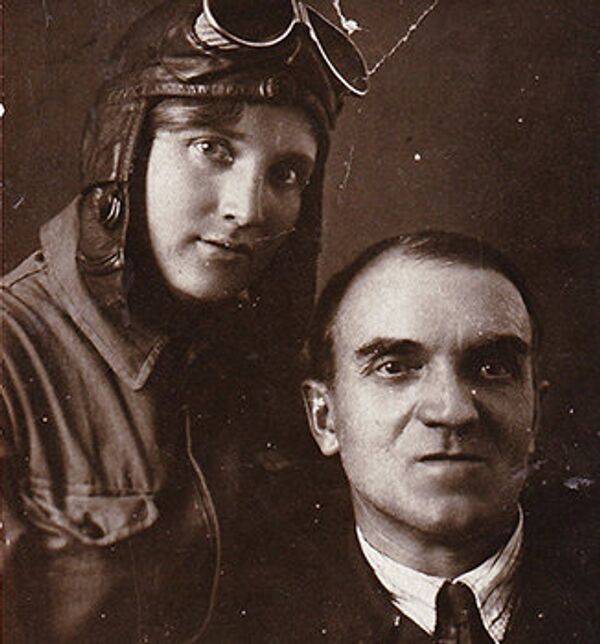

According to family records, Irina was a decorated Soviet ace fighter pilot who was shot down while spying on Finland during the Russo-Finnish war in 1939.

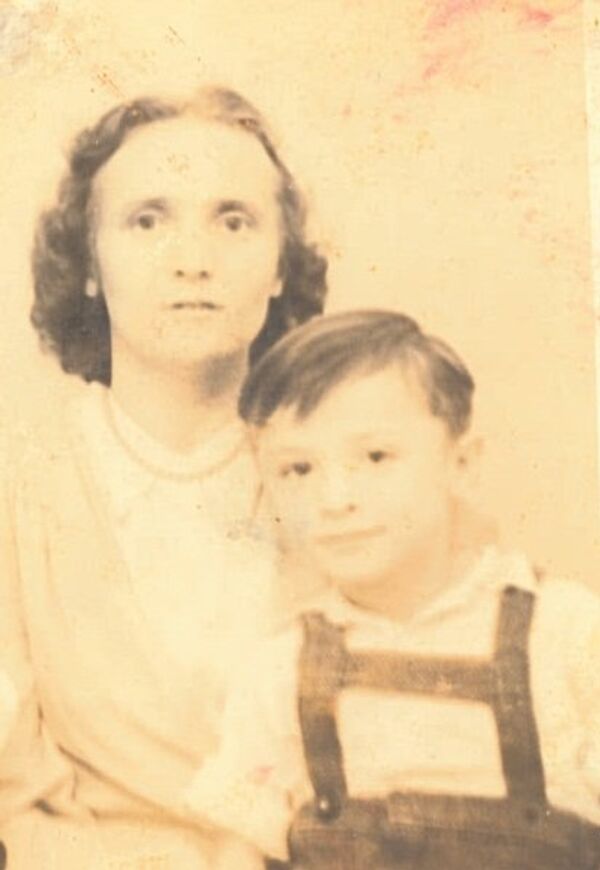

She had married Cornelius Garder, a much older, Menonite man of German descent who soon abandoned her with a young toddler, Leonid. She lost her left leg in a freak train accident but still managed a few years later, at the height of World War II, to walk her way to safety and freedom.

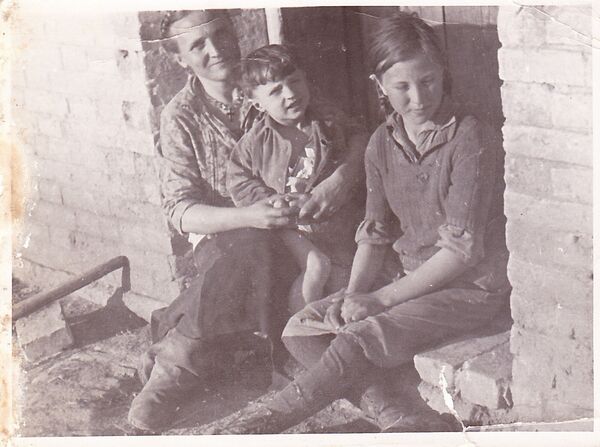

Irina, her younger sister and Leonid spent the better part of a decade on the run, going from Ukraine to Germany to Paris and eventually to America.

“My grandmother basically deserted the army to be with her father and then ultimately left, posing as Germans until they could make their way to safety,” Littrell said.

“The German armies had invaded much of Russia, and the family crossed over to the German side on the pretense that they were all ‘Volksdeutch’ – that is, German immigrants to Russia,” Leonid said, adding, “Those were perilous times, as I remember quite well, with life and death decisions routine.”

Life in America

Finally, with help from the Tolstoy Foundation, a humanitarian organization founded by the youngest daughter of Russian writer Leo Tolstoy to help Soviet émigrés adapt to their new country, the family came to Nyack, New York in the 1950s, and later settled in Vermont.

It was not an easy transition.

“First generation American is sort of a weird place to grow up. Vermont was not a cultural melting pot at all,” Littrell said.

“Up here if you ask somebody what country are they from, they think you’re strange, cause around here there’s only one answer. So they look at you like, ‘uh, America?’” she explained, raising her eyebrows and speaking the last two words slowly, like one might do if they were talking to a person who wasn’t very bright. “My kids were born here, raised here, but still, to real Vermonters they aren’t considered Vermonters yet.”

Bored to tears with her job in insurance sales, in 2007 Littrell and her daughter began selling brownies around town under the ‘Crazy Russian Girls’ name, a nod to the family heritage that had come to define them.

The brownie business was booming, so when the town of Bennington approached Littrell about opening a downtown bakery, she and her future husband, a professional baker, decided to take the plunge, launching the business in 2008 and getting married in the bakery in 2011.

But selling the true flavors of home would take time.

Bennington’s Russian Bakery

At first, Litrell said, people were “a little taken aback because we didn’t have the things they were accustomed to. So in the beginning, I filled my shelves with cupcakes and whoopee pies,” she said, laughing.

The menu now includes borscht on a regular basis, Russian meatball soup and stuffed cabbage. There’s black Russian rye bread, Russian bird’s milk torte and Kievski torte in the glass counters, and the subtle scent of spices and foods not often used in the US.

The bakery itself offers a feast for the eyes, with bold, vivid colors splashed on the walls and an eclectic assortment of stuff squeezed into every available space: old family photos, nesting dolls and religious artifacts, an oversized wooden cutout painted to look like a crazy Russian girl complete with a traditional Russian hat called a ushanka standing in one corner, and yes, even the artificial leg Irina once wore, now donned in black fishnet stockings and a red, high-heeled shoe.

Customers have learned to appreciate the oddities and the newfound connection to Russia, a culture and a country many know little about, thanks to a long Cold War that left mistrust and fear.

“I think both sides have heard the horror stories of it. I think if you’re talking about trying to foster relationships, certainly food and fellowship and friends and family is the way to do it,” said Rev. Robin Greene, another regular, biting into her peasant lunch.

But the rich Russian history that helped to build this bakery, the exhaustion and heartache, the determination, the grit and strength it took for this family to survive and eventually thrive, is a tale that seems familiar to many in this hard-scrabble region of America, she said, where some years, folks feel like they’re doing the best they can just to eke out a meager existence.

The Russian people have “come up through the ashes and through the struggles, and we struggle all the time too, just because of our weather and where we are, our economy. So we can resonate that together,” Greene said.

“No matter how far the oceans are, we can find that common ground,” she added.

Full Circle

For Littrell, it’s a bit like coming full circle, the realization of a dream to build a life in the United States, a dream that began with her grandmother years ago.

“She developed that dream from her father who had told her stories about the freedom in America. I think it was people surviving a really difficult time and loving their country but there was so much hardship and they wanted to find hope for their families,” she said. “And now, I have a responsibility to remember the sacrifices my babushka and my father made.”

Opening a restaurant, she admitted, is hard work. Keeping it open is even harder.

“One of the things that keeps us going is the fact that I’m stubborn, I don’t know how to give up, and I always have this feeling of hope that my grandma taught me.”

Littrell paused for a moment, trying to put into words what it is she longs for now.

Mostly, it seems, a way to connect her two worlds.

“I hope that when people come into this bakery they take away with them a taste of Russian culture, the uniqueness of the food, the stubbornness, the strong personality, all of that,” she said.

“Not only do you come into a restaurant but you sort of come into the family.”