BOSTON, August 29 (by Karin Zeitvogel for RIA Novosti) - Anton Sviridenko’s hands glided over the keys of the baby grand piano in a rehearsal room in the basement of the Berklee College of Music in Boston, his feet rhythmically pumping up and down on the pedals.

“Give me a glissando,” stage performance teacher Larry Watson said, and Sviridenko gleefully raked his right hand down the white keys as Sharin Toribio belted out the last stanza of her composition, “Quiero Vivir” (I Want to Live).

Sviridenko, 22, who prefers to go by the single stage name of Santon, partly because Americans find his Russian last name too hard to pronounce, came to Berklee via a route that started in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he was born in 1991, and the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts, where he attended elementary, middle and high school.

The fact that he is at the prestigious Berklee College of Music at all is a testament not only to his remarkable musical talent but to his family’s and teachers’ determination to help him live life to the fullest.

Three months after he was born, Santon was diagnosed with septo-optic dysplasia, a rare condition that caused his brain to develop abnormally, leaving him blind and with cognitive impairment. He is also autistic and suffers from epilepsy, although he did not have his first seizure until he was 14.

In Russia, the outlook for the family was bleak.

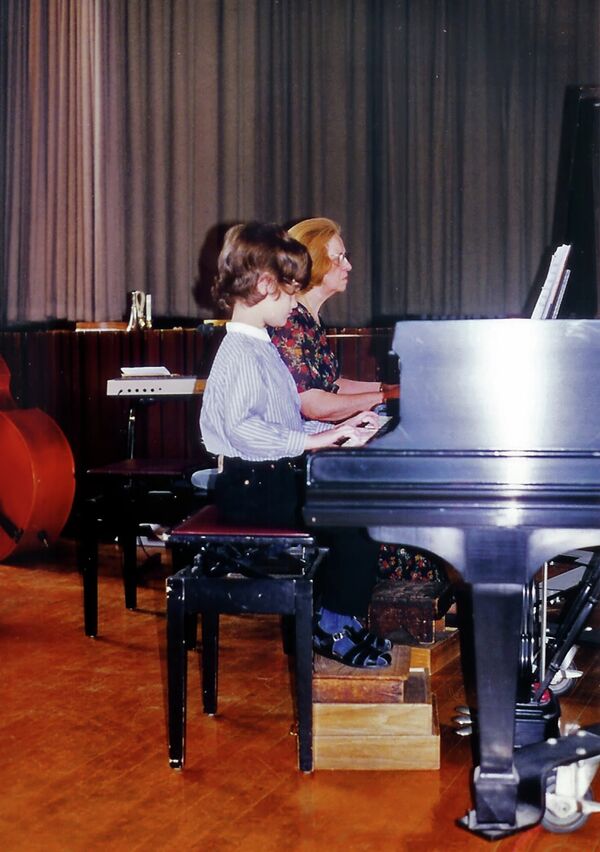

“In St. Petersburg, if your child is blind, by default he goes to a school for the blind and each one of those was a boarding school, and an hour-and-a-half away from where we lived,” Santon’s mother Julia Swerdlov told RIA Novosti as her son took a piano lesson inside a piano repair shop in Newton, Massachusetts, with Ukrainian-born composer and musician Igor Tkachenko.

“If we stayed in Russia, we’d have to give away our child and only see him on weekends. We wouldn’t have the chance to raise our child,” she said.

But what finally pushed the family to leave Russia was a principal at one of the schools for the blind in St. Petersburg, who told Swerdlov and her husband that Santon would only start piano lessons at the age of nine.

When Swerdlov complained that sighted children began taking lessons at 4, the principal shot her down.

“She said, ’You read ‘The Blind Musician’ -- a book by Vladimir Korolenko that we all read in school -- ‘and you think your children will all be geniuses in music,’” Swerdlov said.

“Well, I didn’t say anything but that was the last straw because I was thinking a human being cannot live without art and for someone who is blind, what kind of art can there be besides music?”

So when Santon was 16 months old, the family packed their bags and moved to the Boston area, and to a different, brighter future.

Instead of sending her son to boarding school, Swerdlov started taking him to infant-toddler classes at the Perkins School for the Blind, and he went on to do all of elementary, middle and high school at Perkins, graduating in June of this year.

And, possibly more importantly, he took his first piano lesson at Perkins at age 4. Then, defying the principal in St. Petersburg, he won his first music award at the age of 5.

Santon learns even complex classical pieces by listening to them and memorizing them.

“It takes someone else at least a couple of months to learn a Beethoven sonata. It takes Santon a week,” Tkachenko, who has been Santon’s piano teacher for the past four years, said. “He has a remarkable musical ear and an uncanny ability to hear pretty much every detail in a piece of music.”

He has “the triad of autism, blindness and musical genius that is often found in talented savants -- individuals who have a conspicuous ability, not only over and against their disability but amongst their peer group, including their normal peer group,” Dr. Darold Treffert, a Wisconsin psychiatrist and consultant on the 1988 movie “Rain Man,” which starred Dustin Hoffman as an autistic savant, told RIA Novosti.

“Santon fits that triad, which is remarkable because of its rarity in the already rare condition of savant syndrome,” Treffert said, adding that most musical savants and prodigies are discovered between the ages of 3 and 4, when Santon started playing piano at Perkins, not 9, when he would have started, had he stayed in Russia.

Today, thanks to his parents’ dedication and to his teachers at Perkins and Berklee, Santon is standing on the cusp of a musical career. At the end of this academic year, he will graduate from Berklee and be poised to embark on the life of a professional musician.

Watson said Santon has “the musical talent to be an accompanist to singers, which not all pianists have,” and Tkachenko said he’d like his student to try his hand at composing, but most of all, to keep playing music.

“It’s his life support, his first and primary love in life,” Tkachenko, himself an accomplished musician and composer said.

Other blind and autistic musicians who have attended Perkins and Berklee have gone on to successful musical careers, Treffert said, citing Tony DeBlois and Matt Savage.

Santon himself sees nothing but a future that involves music.

“When I play music, I feel like my brain starts to work,” he said, his sentence punctuated by pauses.

He began folding and unfolding his cane, and rocking slightly back and forth as he looked for more words to express how music makes him feel.

After long minutes, he announced with a dimpled grin: “I feel smile” – and he’s shared that feeling with hundreds already through his music.