MOSCOW, August 29 (Alexey Eremenko, RIA Novosti) – As US destroyers in the eastern Mediterranean are aiming their cruise missiles at Syrian state targets, what can Moscow – which has been vocally opposed to Western military intervention – do and how much does it stand to lose? Surprisingly little on both counts, foreign policy experts say.

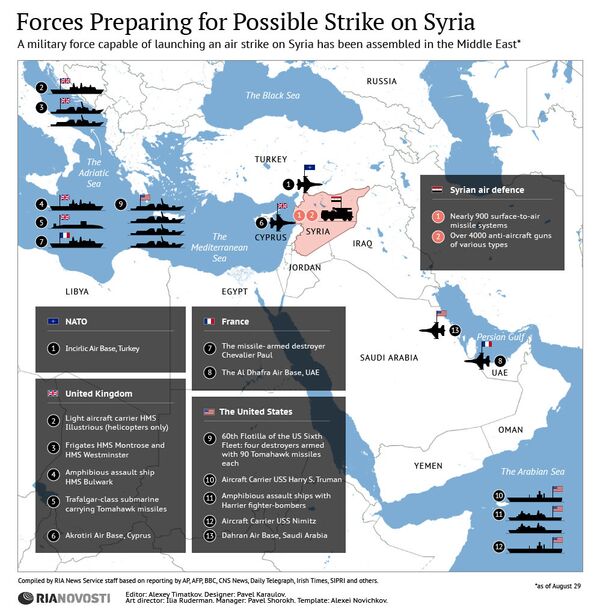

The United States and some of its NATO allies – Britain, France and Turkey – say they are ready to deliver limited strikes against the forces of Syrian President Bashar Assad in retaliation for his government’s alleged use of chemical weapons. Some reports said the punitive action could take place as early as this Friday, though the White House is still reportedly holding off, and anonymous intelligence sources cited by the Associated Press on Wednesday have questioned the reliability of Washington’s evidence about last week’s attack, which killed at least 100 people.

Russia – which has staunchly opposed even much milder forms of Western pressure on Assad since the outbreak of Syria’s civil strife in 2011 – has said the rebels, not the government, may have been behind the chemical attack. But the US-led group’s decision to hit Syrian military targets will not hinge on Moscow’s opinion; if the attack goes ahead, here are some of the consequences for Russia and what it is likely to do and not do in response.

Consequences

- For Russia’s global image

Whether Russia has lost the diplomatic standoff over Syria is a matter of a viewpoint, experts said. Its failure to prevent a Western operation against Assad’s forces could be seen as a defeat, said Vladimir Akhmedov, a leading expert on Syria with the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences. But the fact that Russia managed to delay such an operation for two-plus years counts as a modest diplomatic achievement, argued Vladimir Bartenev of Moscow State University’s faculty of world politics.

Both scholars agreed that the situation is generally similar to the 2003 invasion of Iraq by a US-led coalition, which Russia opposed vehemently in the UN Security Council. Moscow failed to prevent the war, but confirmed its role as an independent global actor – and has since gotten its fair share of “told you so” moments, given the questionable success of the invasion.

- For Russia’s position in the Arab world

Russia has little to lose in the Middle East because its stance on Syria was never endorsed by most Arab nations anyway, experts agreed. The majority of Arabs espouse Sunni Islam, which makes Syria, governed by members of the Shiite-affiliated Alawi religious sect, their natural opponent. Saudi Arabia reportedly tried to court Russia over Syria, proposing an unconfirmed $15 billion arms deal in exchange for Russia withdrawing support for Assad earlier this month. But even if Arab nations did try to court Moscow with such offers, their future positions depend on the military strikes’ success or failure in toppling Assad’s regime, Akhmedov said – and that’s anybody’s guess.

- For Russia’s economy

For decades, Syria has been getting most of its military equipment from Russia, from MiG fighter jets to Bastion coastal defense missile systems, not to mention the state-of-the-art S-300 missile defense systems, which Russia reportedly agreed to sell Damascus before the civil war.

Assad’s possible ouster would harm Russian-Syrian military-industrial cooperation, but not necessarily end it outright because Syrian army troops – currently fighting on both sides – are just too used to Russian arms, said Akhmedov. Iraq and Afghanistan, two countries whose regimes were toppled in the past 15 years by US-led military operations, have resumed buying Russian military equipment, which they had been using for decades. Even in the worst-case scenario, Russia can afford to lose Syria, which accounts for only 5 percent of Russia’s total arms sales, far behind major clients India, Indonesia or Malaysia, said Ruslan Pukhov, head of the Center for Analysis of Strategy and Technologies, a for-profit research group in Moscow.

Meanwhile, oil prices are expected to rise from the current $115 to $125-$150 per barrel over fears prompted by the possible Western attack on Syria, Societe Generale bank said Wednesday. This spells a hefty boost for Russia’s oil-dependent economy, now hovering on the brink of recession, but this would be a short-term benefit at best, said John Lough of British think tank Chatham House.

- For Russia’s naval maintenance base in Syria

Since 1971, Russia has had a small base to repair and restock its battleships in the Syrian port of Tartus. It is currently Russia’s last military facility outside the former Soviet Union – but this shard of Soviet imperial glory has only token significance, experts say. “The base just doesn’t matter,” said Pukhov, pointing out that the tiny facility comprises only a few barracks and maintenance buildings and is capable of accommodating no more than two mid-sized ships.

What Would (& Wouldn’t) Russia Do?

To Do List:

- UN Security Council veto

Moscow wants any military action to go through the UN Security Council – but will likely block any resolution to authorize it, citing lack of conclusive evidence that Assad’s regime, not the insurgents, was behind the attack, all experts interviewed for this article agreed.

“[Russia] will claim – in strong language – that any punitive strikes or retaliation against the Syrian regime are illegal – as this is the position it has taken on every such punitive strike by the US since the early 1990s,” said Roy Allison, an international affairs expert with St. Antony's College of the University of Oxford. (One exception was the proposed NATO military operation in Libya in 2011, on which Russia abstained in the UN Security Council, paving the way for it to go forward; this decision was made under President Vladimir Putin’s relatively more liberal predecessor, Dmitry Medvedev. The same was true of the 2001 US-led intervention into Afghanistan, another major military operation which Russia did not oppose.)

- Geneva 2 conference

Russia will also likely continue to push for a political solution to the civil war in Syria – probably through its pet project, the so-called Geneva 2 conference, meant to bring representatives of Assad and the rebels to the negotiating table. Though airstrikes would likely boost bloodlust on both sides, Moscow will still work to set up the conference, possibly with the help of the United States, Bartenev and Akhmedov said. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said Monday that the US State Department still supports the idea of Geneva 2.

- Aid for Assad’s regime

Moscow will continue to support the Assad government with weapons and humanitarian aid, as it has in the past, said Olga Oliker, an international policy analyst with the RAND Corporation, a US-based non-profit think tank. Russian analysts agreed, saying that Moscow appeared to have invested a considerable sum in Assad’s regime through loans and financial support, as well as providing it with firearms, though no estimates for Russia’s total spending on Syria are available. However, no increase in military cooperation should be expected, said Bartenev of Moscow State University.

To Avoid List:

- Getting cozier with Iran

Syria’s No. 1 regional ally is Iran, the world’s main stronghold of Shiite Islam. Russia has a track record of working with the Islamic Republic: It has built a nuclear plant in the Iranian city of Bushehr and agreed to sell Tehran some S-300 air defense systems, though pulled out of the deal in 2010, largely under Western and Israeli pressure. It is feasible that Moscow could consider deeper involvement with Iran, but the Kremlin would not want to be drawn into any Iran-related escalation of the Syria conflict, Allison said. He added that, while Moscow would try to preserve its relations with Tehran, it would also strive to limit any damage to its generally cordial relations with Israel. Russia fears empowering Iran too much, given the country’s nuclear ambitions and reputation as a regional troublemaker.

- Destroying relations with the US

Russia’s relations with the United States are in disarray, but Syria is only one item on the agenda, said Oliker of RAND. Moscow may make some symbolic moves toward suspending defense cooperation with Western countries, including on Iran and Afghanistan, but “it is unlikely that Russia will follow through on threats of this kind,” said Lough of Chatham House.

- War

One thing Russia will not do is fight for Syria. Lavrov said it explicitly Monday, and pundits were unequivocal in agreeing he meant it. Like many recent US-led military operations, a strike against Syria simply would not touch enough on Russia’s vital geopolitical interests, leaving Moscow without an incentive to expend the considerable economic and military effort required by overseas military operations, analysts said. Another concern would be public opinion: About the only example of Russia’s military involvement against a US-led military offensive was a sudden takeover by Russian paratroopers of a Kosovo airport in 1999, which left the world slack-jawed but had few consequences otherwise. In that case, however, Moscow could boast to the Russian public of its bold support for the Serbs, a brethren Slavic people perceived as unfairly attacked by the West.

This article has been amended to include the mention of the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan as an example of a US-led military operation not opposed by Russia.