MOSCOW, September 6 (Alexey Eremenko, RIA Novosti) – On a warm August day, a group of believers walked the streets of Moscow dressed like pirates, with colanders on their heads, heading to a macaroni-and-beer party to honor the Flying Spaghetti Monster.

But however joyful and tongue-in-cheek their rally might have seemed at the time, some participants now face up to 15 days behind bars on charges of violating the law on public gatherings.

Irony, the lifeblood of hipsters and the byword of 21st century culture, is increasingly embraced by young, affluent, educated Russians who are now taking their tongue-in-cheek jokes to the public.

But the irony has so far been lost on the Russian authorities, which ban even seemingly apolitical events such as Monstrations, or snowball and pillowfight flashmobs, both prohibited by the St. Petersburg administration in June 2012 and January 2013, respectively.

To an extent, the powers-that-be have a point, because the carnival spirit and absurdist humor are recognized as an implicit means of resisting the state’s deadly serious propaganda, sociologists say.

“This is how young intelligent people defend themselves from the leaden pomp produced by the authorities,” said Olga Kryshtanovskaya, an expert on Russian elites at the Sociology Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Touched by His Noodly Appendage

The Russian Pastafarian Church has registered 15 branches across the country since July. But that is only because the law bans the authorities from rejecting registration requests for any religious group, the church’s supreme cleric said.

The Russian offshoot of this ironic faith – which originated in the United States in 2005 as a protest against Christian creationism encroaching on school curricula – now boasts some 15,000 members, said the cleric, who identifies himself only as Pastriarch Kama Pasta I.

In some regions, Pastafarians held events without falling afoul of local administrations, but Moscow City Hall rejected an application for a “Pasta Rally” in August, saying that this type of event was not listed in the federal law covering public demonstrations, media reported at the time.

Pastafarians tried to hold a party in café at a Moscow garden, but the playful atmosphere was dampened when radical Christian activists turned up and doused them in ketchup and reported them to police as an unsanctioned rally. A police protocol published by the Pastafarians claimed they never applied for a permit, though the religious group denied this.

Eight Pastafarians are now awaiting court hearings on charges that could lead to fines of up to 30,000 rubles ($1,000) per macaroni-lover or 15-day detentions.

“We just wanted to troll the church a bit,” said Kama Pasta, a fit, animated man in his late 30s, a self-admitted atheist (this is okay in Pastafarianism) who – the rest of the time – is a businessman.

“We don’t want to make our campaigning too serious. After all, we stand to promote critical thinking and self-irony,” said Kama Pasta I.

“But when we told as much to one judge, she didn’t understand it at all and just said, ‘you’re a sect.’”

“I don’t think our mission here will be finished any time soon,” the Pastriarch said.

Don’t Mess With the Patriarch

Last Tuesday, St. Petersburg police entered a local erotica museum and seized a copy of a painting of Russian President Vladimir Putin and his US counterpart Barack Obama locked in a penis-measuring contest.

Eight days earlier, they also seized four paintings at another private museum in the city, owned by the same entrepreneur. The paintings showed a mafia-tattoo-covered head of the Russian Orthodox Church, and Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in drag.

The crackdown was initiated by local legislator Vitaly Milonov, best known to the world for penning St. Petersburg’s controversial ban on “gay propaganda among minors,” a version of which became federal law in June, prompting an international outcry and calls for a boycott of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.

“I’m perfectly fine with irony, I dabbled in it myself in my youth,” Milonov, a self-confessed hippie-turned-ultraconservative Christian, told RIA Novosti.

“But there are lines that shouldn’t be crossed,” he said by telephone Tuesday. “They are infringing on my value system when they attack the Holy Patriarch.”

The museum’s owner complained to prosecutors about the police raid. But while an investigation is pending, the artist who depicted the church’s head as a mobster has requested asylum in France

The museum that housed his paintings reopened on Thursday after being temporarily shut down by police, but now faces expulsion from the space it is leasing over “political actions,” which are banned under the lease agreement, the building’s owner said.

The Russian Orthodox Church has become increasingly intertwined with the state since Patriarch Kirill’s enthronement in 2009, and is expanding its presence in public institutions such as schools and the military, introducing elective religion classes in schools and chaplains in the army. Kirill endorsed Putin’s presidential bid in 2012.

This trend has drawn criticism from segments of society that resent the erosion of the separation of the church and state. One of contemporary Russia’s most high-profile political protests took place last year in a Moscow cathedral. Punk band Pussy Riot performed their angry anti-Putin song in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior – a building that has come to symbolize post-Soviet Russia’s ties to the Russian Orthodox Church. Three band members involved in the protest were given two-year prison sentences – sending a powerful message to critics.

Hobbits Vote Yes

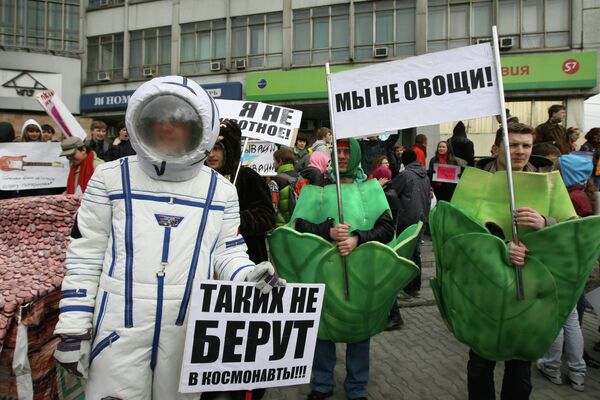

Absurdist humor first appeared on the scene in post-Soviet Russian politics a decade ago in Siberia, with “Tanya, Don’t Cry!” and “Where Am I?” It was 2004 – and artist Artyom Loskutov held the country’s first Monstration, a public rally with deliberately nonsensical slogans, in the city of Novosibirsk.

By 2013, 15 cities across the former Soviet Union had hosted Monstrations. This year saw several thousands of people come out onto the streets on May 1, holding banners that read “Put a Banana in Your Ear” and “Hobbits Vote Yes.”

These events are meant to be apolitical, but Loskutov conceded in an interview that the idea originated as a backlash against the “pointlessness” of annual May 1 political rallies held by the Russian Communist Party after the Soviet Union’s demise.

Their real purpose was not to “troll” the Communists – or, later, demonstrators at state-endorsed political events – but to bring together people averse to meaningless political clichés, said Loskutov, 26.

But he said that police would detain Monstration-ers and that getting permits for the events from the authorities, who remain distrustful of such rallies, is “a struggle” to this day.

Loskutov himself was busted in 2009 for marijuana possession and spend a month in custody. He called the case fabricated in retribution for his activism and said this week he is considering leaving Novosibirsk because he is too tired to fight a constant stream of petty cases mounted against him.

Protest Through Irony

Russia’s thinking classes have long invoked irony as a way of mocking state bureaucracy, which they view as all-powerful but slow-witted and prone to primitive solutions, especially on propaganda, experts said.

Kryshtanovskaya of the Russian Academy of Sciences cited the long tradition of Soviet political anecdotes as a predecessor of both Monstrations and Pastafarians. Jokes such as “can a snake crawl along the Party line? – No, it’ll break its spine,” were recounted in millions of kitchens nationwide in late Soviet times.

This battle for irony comes in waves, and has intensified since the outbreak of still-ongoing opposition protests in Moscow in 2011. These public displays of discontent with the status-quo were driven to a large extent by a hipster generation irked by the government’s ham-fisted control of media and public life, sociological studies of the protest movement showed.

Memes, including Trollface and Harry Potter, featured heavily in posters and placards carried at public rallies.

However, the government responded by ramping up its humorless propaganda drive aimed at its core constituency of poorly-educated public sector employees and the working classes – who are largely unresponsive to irony, said sociologist Lev Gudkov.

Things are unlikely to get easier for the likes of Kama Pasta I’s flock in the years to come, added Gudkov, who heads the respected independent pollster Levada Center.

“The Russian government always had problems with its sense of humor,” Gudkov said.

(The story was amended to say the Pastafarians claimed to have held the dispersed party at a Moscow café, not public space.)