Twenty years ago, Russia was locked in a constitutional crisis that culminated on October 3-4. Lawmakers and officials who did not want to cede power to the new president had barricaded themselves in the Supreme Soviet, or parliament, building. On October 4, troops acting on then-President Boris Yeltsin’s orders took the building, now known as the White House, by force. According to official figures, 187 people died and a further 437 were injured during the unrest.

1/16

© RIA Novosti . Vladimir Vyatkin

Twenty years ago, Russia was locked in a constitutional crisis that culminated on October 3-4. Lawmakers and officials who did not want to cede power to the new president had barricaded themselves in the Supreme Soviet, or parliament, building. On October 4, troops acting on then-President Boris Yeltsin’s orders took the building, now known as the White House, by force. According to official figures, 187 people died and a further 437 were injured during the unrest.

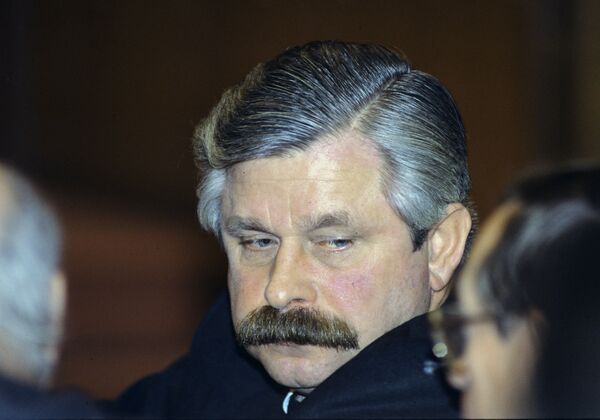

By late 1992, newly-independent Russia was embroiled in a domestic crisis that saw elements of the former-Soviet political structure, such as senior figures in the Supreme Soviet and members of the Congress of People’s Deputies, led by Ruslan Khasbulatov, pitted against new President Boris Yeltsin, his government and some regional leaders.

On December 9, 1992, the Congress of People’s Deputies refused to appoint Yegor Gaidar, Yeltsin’s candidate, as Prime Minister. On December 14, 1992, Viktor Chernomyrdin was appointed Prime Minister. Pictured: Viktor Chernomyrdin, at the VII Congress of People’s Deputies, March 10-13, 1993.

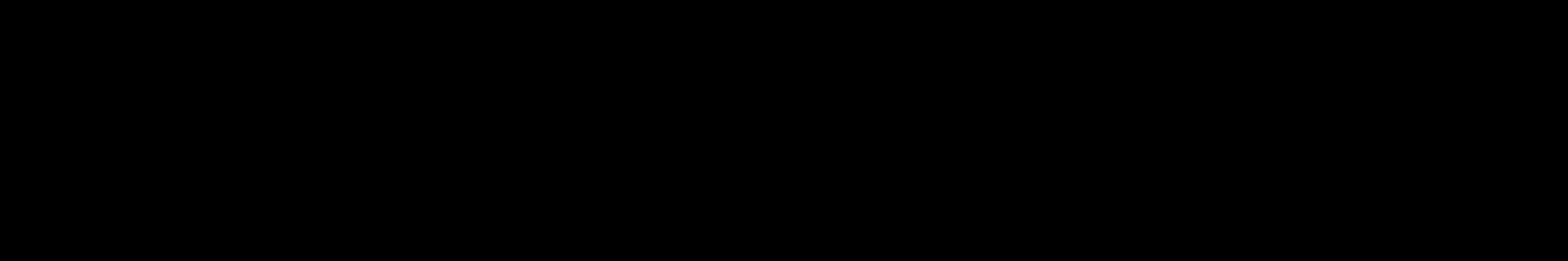

On March 28, 1993, the Congress of People’s Deputies rejected a draft resolution on holding early presidential and parliamentary elections, and launched impeachment proceedings against President Yeltsin. This attempt failed, but the next day, the Congress voted to hold a nationwide referendum on April 25.Pictured: Yeltsin’s supporters rally in Moscow.

Russians remember being urged to vote “Yes, Yes, No, Yes” on the referendum’s four questions. The first question asked whether they trusted Russian President Boris Yeltsin.58.7 percent said “yes.”

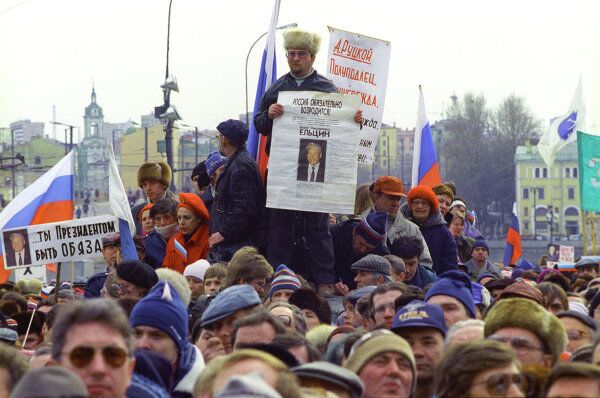

Pictured: Police during pre-referendum protests.

Pictured: Police during pre-referendum protests.

There were clashes between the opposition and riot police.

Pictured: Protests, May 1, 1993.

Pictured: Protests, May 1, 1993.

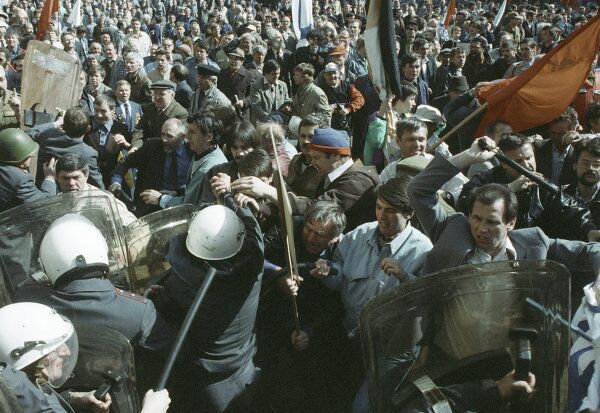

Pictured: Opposition protesters throwing bricks at police units.

Police and members of the public were injured in the violence.

On September 21, 1993, President Boris Yeltsin issued Executive Order No. 1400, dissolving the Congress of People’s Deputies and the Supreme Soviet. The Constitutional Court ruled that the President had acted unconstitutionally. The Supreme Soviet passed a resolution terminating Yeltsin’s powers and appointing Vice President, Alexander Rutskoi, pictured, as President.

The Supreme Soviet also announced that it was convening the 10th Emergency Congress of People’s Deputies, which was held by candle-light because the building’s power and water supplies had been cut off.

11/16

© RIA Novosti . Vladimir Vyatkin

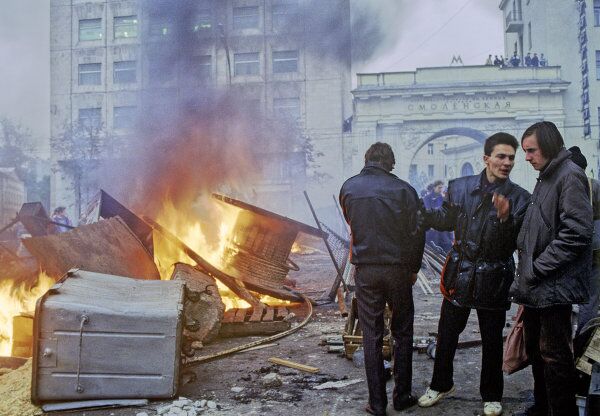

The Supreme Soviet building was under lockdown. Deputies arriving in Moscow to attend it were not allowed in and instead gathered at local Soviets (Councils) in Moscow.

Supreme Soviet supporters took to the streets, built barricades and lit bonfires.

A pro-Yeltsin rally near the Moscow City Soviet (Council) building.

Yeltsin’s supporters guarded barricades on Stanislavsky Street.

15/16

© RIA Novosti . Vladimir Fedorenko

Moscow during the 1993 constitutional crisis. The former Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) building can be seen on the right.

16/16

© RIA Novosti . Vladimir Vyatkin

According to official figures, 74 people were killed in the violence that day, including 26 military personnel and police officers, and 172 more people were injured. Fire gutted eight floors of the Supreme Soviet building.