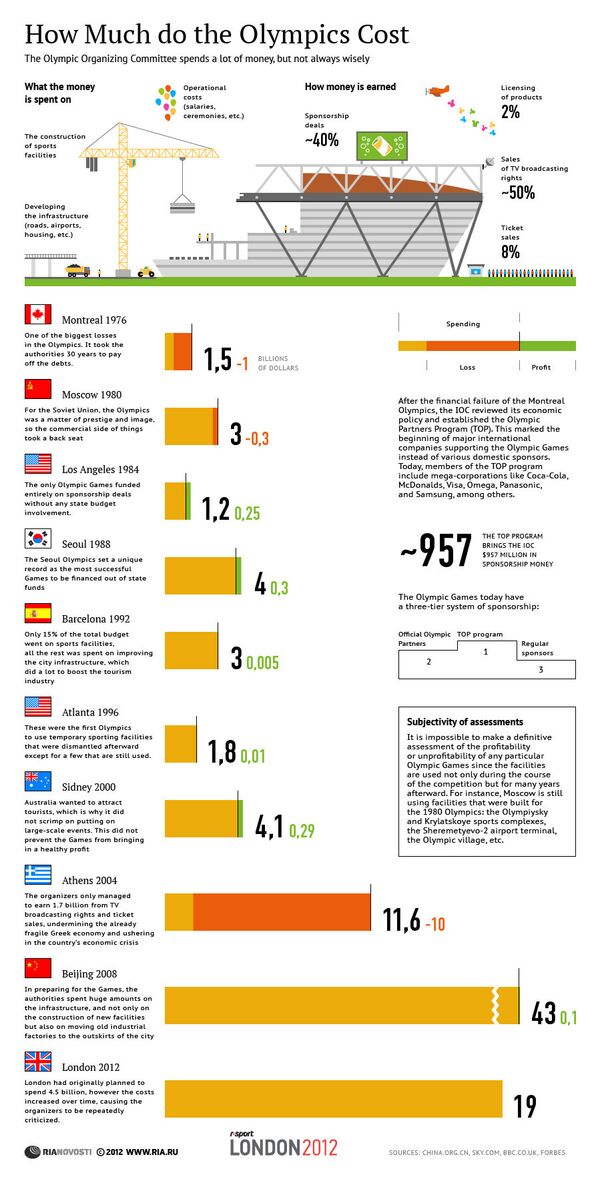

SOCHI, December 19 (Alexey Eremenko, RIA Novosti) – The eye-watering $51 billion spent on the 2014 Winter Olympics is justified by Russian authorities as an attempt to put host city Sochi on the world tourism map.

Experts say the Soviet-era resort will face a tough and uncertain struggle in its battle for visitors’ money, however.

“They think in Sochi that everyone knows them now. But knowing does not mean coming to visit,” said Russian Union of Tourism Industry deputy head Yury Barzykin.

Sochi, a city of 370,000 on the Black Sea coast in the shadow of the Caucasus Mountains, was once deemed something of a Soviet Florida in terms of popularity and for the palm groves that lined its streets.

It suffered something of a decline since its heyday, but has now been rejuvenated with the addition of world-class sports venues, skiing resorts and dozens of hotels.

A Lenin statue still stands in the city center, next to a Stalin-era neoclassic style former arts museum. The Bolshevik champion of the proletariat is now dwarfed by gargantuan high-rise hotels encircling him on all sides.

According to regional government data, the city added 1 million square meters of authorized real estate in recent years – and seen an equivalent amount of illegal construction.

Krasnaya Polyana, a mountain town some 37-minutes from Sochi by high-speed train, is already a popular skiing resort and has now added biathlon, bobsleigh and ski jumping facilities. Six new sports venues created at the Olympic coastal cluster include the 40,000-seat Fisht stadium and the Bolshoi ice hockey arena.

The construction binge was no accident. The government has demonstrated in recent years that its sees epic projects as a major boon for development.

Russia pumped an unprecedented $20 billion into preparing for the 2012 APEC summit in the Far East city of Vladivostok. It is estimated the 2018 football World Cup in Russia will cost another $20 billion.

Such programs often fall victim to corruption, however, and the after-effects are not as long-lasting as proponents would like.

President Vladimir Putin had to admit last month, for instance, that Far East development is still proceeding at a crawl. APEC-related construction, including the new university campus and the Golden Gate-style bridge in Vladivostok, are already showing signs of decay.

Olympic authorities claim that legacy is a core motivating factor when choosing a venue for Games, but the only immediately clear outcome of Sochi will be a mountain of debt.

Venues in Sochi have so far served as a burden for their developers. Most investors are government corporations supported with loans from state-owned Vnesheconombank.

State-run Gazprom and Sberbank, as well as privately owned Basic Element and Interros have sought restructuring for multibillion state loans, Vedomosti business daily reported in November. The government remains noncommittal over whether those requests will be granted.

And most of the venues will become state property after the Games, which analysts interpret as confirming their lack of commercial viability.

One major exception is the Krasnaya Polyana skiing resort, which will remain the property of Russian tycoon Vladimir Potanin’s Interros, according to Vedomosti.

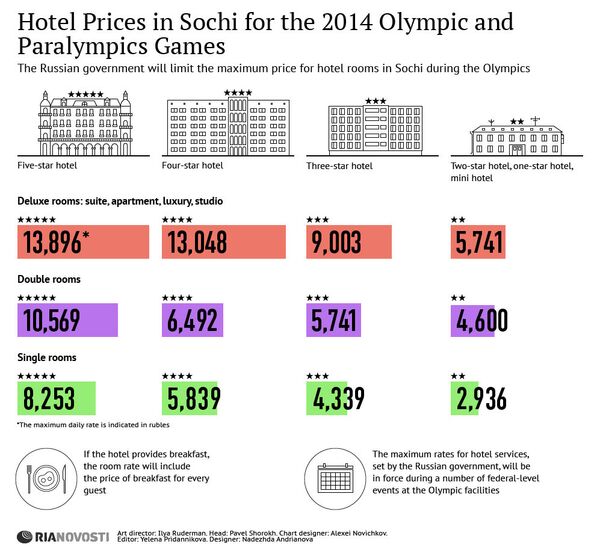

Prices there will still scare many anyway though.

“They’ll be lucky if they fill their own hotels,” said Ilya Umansky, vice president of the independent Association of Tour Operators of Russia.

Most venues will retain their original purpose. Some, including the Bolshoi arena, will be converted for use as multipurpose concert halls or expo centers, although officials concede filling them in Sochi will be a hard task.

Concerns about potential future utilization of venues prompted the decision to limit capacity at Bolshoi ice dome to 12,000, far less than the 18,000 seats at a Vancouver stadium used in the 2010 Winter Games, said arena deputy general manager Uliana Barbysheva.

The dilemma tourism operators will constantly face is balancing the need to keep prices low as possible, while ensuring investments costs can be recovered.

“They’ll need prices higher than in Miami to recoup the investments in a decade or two,” said leading architecture and urban development expert Grigory Revzin.

Sochi attracted 4 million tourists in 2012. That figure, while high, marks a point on a downward trajectory that has been steady and lasted for years.

A vacation in the resort costs more than in Turkey, Egypt or Thailand, all popular destinations for Russian tourists. The city is oversupplied with hotels, which means that some will likely go bankrupt after the Games.

Sochi offers plenty of holiday homes for sale. But prices for a one-bedroom apartment start at 3 million rubles ($90,000), according to Mikhail Titov, head of the Realtor Guild of Sochi.

An equivalent sum could buy a two-bedroom apartment, with a swimming pool, in the southern Spanish resort town of Aguilas, according to realty website Kyero.com.

Local agents counter overseas competition by appealing to rich provincial Russians’ wariness of going abroad.

“I tell clients: “You want that house in Montenegro? What if the Americans come and bomb it?’” Titov said.

Some are buying that line, he said.

As for foreigners in Sochi, there have also been few of those, although Cuban leader Fidel Castro did once pop by in 1972.

City authorities hope the Olympic exposure will change that, even if Sochi will find it hard to compete with rival, low-cost holiday destinations.

The city has no experience with foreigners and struggles to communicate in English, said Alexander Maklyarovsky, head of the inward tourism department at major Russian tour operator KMP Group.

And hospitality is also an issue. Sochi mayoral advisor Olga Nedelko admitted that locals are used to seeing tourists as a nuisance, although the City Hall has run master classes in politeness in an effort to change this attitude.

The resort still has some potential, especially for domestic tourism.

Medical tourism represents one opportunity for the former Soviet-era health resort, where sanatoria – such as the Matsesta that once treated Stalin and Brezhnev – still abound.

Eco-tourism is also an option, as is corporate tourism to the city’s now-numerous five-star hotels, said Umansky of the Association of Tour Operators of Russia.

But all of it needs much more work. Environmental tourism is still at a rudimentary stage, the sanatoria are mostly a Soviet legacy, and corporations have yet to be lured to Sochi.

City Hall created a special commission in the fall to define the city’s post-Olympics image, Nedelko said. The mayoral advisor did not say why it was not done sooner.

If anything, the clues to the future survival of Sochi as a major destination may lie in drawing on the Soviet past, when state employees were treated to vacations at the government’s expense.

“Maybe they can start sending Siberian workers on state-funded trips there, Soviet-style,” said Maklyarovsky. “Even to the Hyatt. Why not?”