MOSCOW, January 14 (Kevin O’Flynn for RIA Novosti) – Intrigue, ideology and victory against the odds – an exhibition in Moscow held to coincide with the upcoming Sochi Olympics explores that and more about the history of Soviet participation in the Winter Games.

The show brings together Games-related ephemera, photographs and a trove of declassified documents from Central Committee meetings, including one on a doomed Sochi hosting bid.

Soviet authorities only agreed to send athletes to the Winter Games for the first time in 1955, and even then, only after doing whatever they could to ensure their competitors would be best positioned to come out on top.

The Soviets had considered entering the Winter Olympics in 1952 – their athletes took part in the Summer Olympics that year – but demurred over concerns about where the athletes would live.

With the 1952 Winter Olympics taking place in Oslo, Norway, a NATO member, the Soviets delayed their debut until the Games in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, in 1956 as a mood of relative political liberalization had taken hold.

The exhibition, called “The White Games. Top Secret. USSR and the Winter Games, 1956 to 1988,” shows how the decision to lift the country out of international sports isolation was taken at the highest level.

The Central Committee received detailed reports on how many athletes would go, as well as updates on training, how much foreign currency they were to be given, and how many days each team member would be allowed to remain abroad.

Unsure of success before their winter debut, the Soviets tried to have the decidedly non-wintry sports of boxing, gymnastics and chess added to the Winter Olympic Games roster.

The need for assured victories required some adaption. Russians traditionally played bandy, a sport resembling ice hockey but played outside with a ball.

Viktor Shuvalov, 90, a member of the Soviet team that won the 1956 hockey Olympics gold medal, recalls their first attempt at the foreign variation as a frustrating exercise.

“We were used to hitting the ball, not sliding [the puck] in Russian hockey. How we got fed up with that puck,” he told Moskovskiye Novosti newspaper. “After training we were covered in bruises, scratches … It was horrible to see.”

But the preparations paid off. The Soviets won the Ice Hockey World Championships in 1954, before winning the Olympic gold two years later. In fact, the Soviet Union won the most medals at the 1956 Games, thus beginning a dominance of winter sports that lasted until the end of the Soviet Union in 1991.

If many of the documents on display deal with the minutiae of sports organization – the plan for training sportsmen was fulfilled to 75.6 percent, Kremlin officials were told at one point –there are also glimpses into how ideology was never far from the lives of the sportsmen.

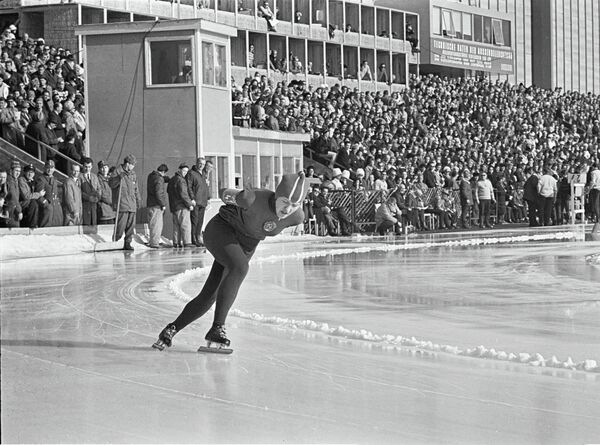

One display shows a letter to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev from champion speed skater Lidiya Skoblikova, who won four gold medals at Innsbruck in 1964, asking to be made a member of the Communist Party.

As Skoblikova explains, when asked at a press conference in Innsbruck whether she was a party member, she could only answer that she belonged to the party’s youth section. In the end, Khrushchev came through and granted her the long sought-after membership.

Another telegram in 1979 signed by the national hockey team’s top players, including legendary goaltender Vladislav Tretyak, reached then Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. It is written in finest Sovietese: “Dear Leonid Ilyich, we inform you that Soviet hockey players have fulfilled the mandate of the motherland, and in an exceptionally hard-fought sporting battle beat a team made up of the strongest professional players from the USA, Canada and Sweden.

“This victory we dedicate to the Communist Party which has brought us up, and the Soviet people, who are preparing for the glorious event – the elections in the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.”

A more secret report on the 1978 World Ice Hockey Championships in Prague talks about a “pro-Western mood” among Czechoslovakian hockey supporters, who not only backed their own side, but also any Western team. The account takes exception to the anti-Moscow mood created by people in the crowd, including schoolchildren, egging on teams facing the Soviets.

When the Soviet side won, the report complains that local officials fled rather than having to perform the standard congratulation rites.

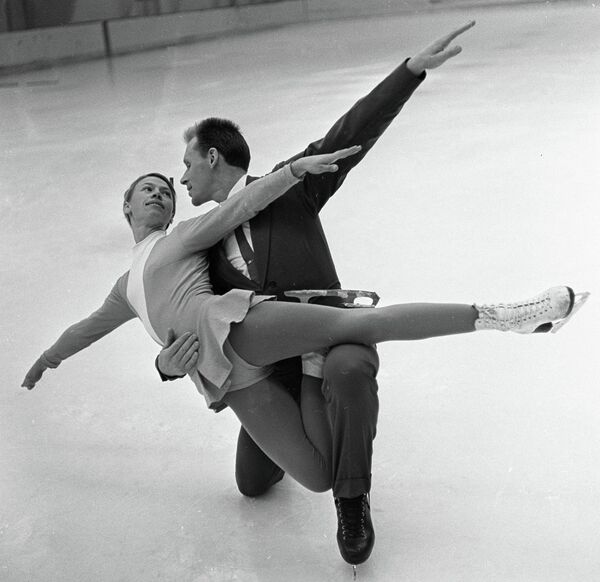

One letter from 1972 touches on the theme of corruption and bias among ice-skating judges. It complains about a Polish ice-skating judge who reneged on a deal with a Soviet judge to place the Soviet pair in fourth place in exchange for the Poles getting sixth. Other judges listed in the letter are also accused of bias against Soviet skaters.

By the 1980s, the Soviets were still leading the pack, but looked around at increasingly confident rivals with concern, especially with their own facilities either crumbling or simply nonexistent.

Astoundingly, the Soviets managed to win the two-man bobsled event at the 1988 Games in Calgary, despite the country lacking its own course. Vladimir Kozlov, who was on the team, told Moskovskiye Novosti that local factories were used to create a bobsled for athletes and that a track was created by manually packing snow.

The exhibition briefly hints at the discontent felt by some athletes in a Central Committee report written after two-time Olympic ice skating pair champions Oleg Protopopov and Lyudmila Belousova defected to Switzerland in 1979.

In the 1980s, the Soviets were beginning to consider putting in a bid to host the Winter Games for the first time.

During a Central Committee discussion on putting forward St. Petersburg as a host for the 1996 Games, one official argued in favor by pointing to the example of Yugoslavia, which earned a tidy profit by holding the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo.

Controversial International Olympic Committee chief Juan Antonio Samaranch, who earned his position thanks to Soviet support, makes an appearance in an early 1980s transcript of a meeting with Heydar Aliyev, a top Communist Party functionary who was later to become president of Azerbaijan.

“It is undoubtedly many times easier to organize Games in socialist countries than in the United States, so I am calm about Sarajevo, but Los Angeles will create a lot of difficulties and problems,” said Samaranch, speaking of the 1984 Winter and Summer Olympics.

Samaranch’s parting words in the meeting are “I have a good memory, and I remember my friends.”

St. Petersburg’s bid failed all the same, and when the idea resurfaced in 1989, Moscow considered three sites: Krasnaya Polyana/Sochi, the venue of next month’s Games, Alma-Ata, then-capital of Soviet Kazakhstan, and Bakuriani in Georgia.

The options were finally narrowed down to Sochi, but the breakup of the Soviet Union ended its bid.

Officials estimated the Black Sea resort would require an investment of 650 million rubles if it was to host the Games. Even accounting for inflation, that figure amounts to roughly 70 times less than the $50 billion or so it has cost to prepare for the 2014 Games.

“The White Games. Top Secret. USSR and the Winter Games, 1956 to 1988” runs until Feb. 23. More details available at www.rusarchives.ru