MOSCOW, February 5 (Alexey Eremenko, RIA Novosti) – An ill-conceived poll posted online for just 12 minutes is all it took to precipitate the latest turn of the screw on Russia’s constricted independent media scene.

As of Wednesday, Dozhd – named after the Russian for “rain” – a youthfully dilettantish television station that has since its creation in 2010 relished in thumbing its nose at the authorities, had been dropped by all the country’s major cable and satellite providers.

Dozhd owner Alexander Vinokurov says the station has shrunk its footprint of potential viewers to 2 million, down from the previous 17 million, a development certain to send advertisers fleeing.

“We believe this is an attempt to shut down the channel while saying that it wasn’t shut down,” Vinokurov, a 44-year old investment banker who created his own media holding in 2009, said Tuesday.

Causing Offense

The triviality of what caused Dozhd’s downfall speaks volumes about the scant room for contrarian views in a climate in which, critics say, the state monopolizes the message, as well as the medium.

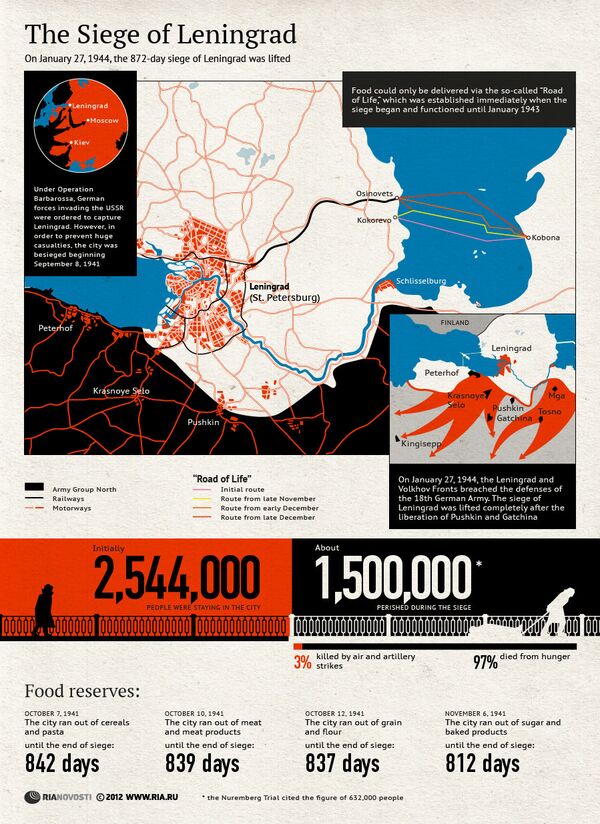

On January 26, during a studio discussion on World War II, the station’s social media team posted a poll inviting viewers to vote on whether they thought the Soviet Union should have surrendered Leningrad – now St. Petersburg – to invading Nazis to prevent mass deaths, rather than endure a 900-day siege.

The survey was immediately pulled in recognition of the raw emotions still provoked by this almost unimaginably horrific chapter of Russian history, but the damage had already been done.

Pro-Kremlin lawmakers and government officials were the first to lash out.

"I have no name for these people. They're non-people," said Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky.

Cable Broadcaster Association head Yury Pripachkin quickly followed suit, urging members of his organization to “exercise certain censorship functions.” The country’s largest cable and satellite television providers duly complied.

Retribution for Reporting

Dozhd founder and general director Natalya Sindeyeva calls what is happening to her station retribution for its independent journalism.

One recent item in particular is held up as a likely potential spark for Dozhd’s plight.

The station picked up a report issued in November by opposition activist and politician Alexei Navalny accusing leading lawmakers and the Kremlin’s powerful domestic politics chief Vyacheslav Volodin of owning lavish country mansions surely unaffordable on government salaries.

State Duma deputy Sergei Neverov publicly denied the allegations, which he characterized as a smear campaign. A parliamentary commission overseeing lawmakers’ income declarations looked into Navalny’s report, but no legal action followed.

Dozhd representatives avoided directly pointing fingers at the Kremlin, but others are more categorical about the authorities’ role.

“The campaign definitely has a political motivation and uses a formal pretext,” said Mikhail Vinogradov, head of the St. Petersburg Politics Foundation think tank.

The Kremlin rights council, an advisory body with a record of making outspoken statements, has denounced the campaign against Dozhd as unconstitutional and called on the Interior Ministry to investigate.

Reversal of the Thaw

Pavel Salin, a political studies expert at the Government Financial University in Moscow, suggested that Dozhd was only the latest victim of the Kremlin’s quest to bring to heel those media outlets that gained prominence during the relative thaw of Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency from 2008 to 2012.

Last year’s announced liquidation of state-owned news agency RIA Novosti may be another bid to curb off-message media organizations endorsed by the former president, Salin said.

The entity replacing RIA Novosti – Rossiya Segodnya (“Russia Today”) – is headed by Dmitry Kiselyov, who made his name as an abrasively government-loyal television personality. He expressed his views on the Dozhd poll controversy in typically forthright fashion in his weekly news show Sunday.

Responding to a defense of the poll by television presenter and socialite Ksenia Sobchak, who argued that only answers, and not questions, should be deemed “amoral,” Kiselyov posed his own provocative query: "What if someone perhaps asks, ‘Will Ksenia Sobchak finally come to her senses and give up hard drugs after her 14th abortion?’ Would that be alright?"

Beginning of Media Decline

In the 1990s, many journalists and editors were attacked and even killed for doing their work. The systemic government-led impulse to clip independent media’s wings dates back to 2000, in the early days of President Vladimir Putin’s first term.

A sign of clouds gathering over what was then the standard-bearer of openly critical reporting – privately owned and virulently anti-Putin NTV – came with a curious petition signed by a group of academics in St. Petersburg taking exception to the irreverent tone of a satirical rubber puppet show aired by the broadcaster. Later that same year, NTV was wrested away from tycoon Vladimir Gusinsky by the media arm of state-owned natural gas giant Gazprom. Other stations, such as TV-6 and REN-TV, carrying punchy news broadcasts also subsequently came under pressure and were eventually either closed or toned down their coverage.

Latest Wave of Pressure

In 2010, Dozhd emerged as the country’s first independent general news channel.

But the bold reporting of anti-government street protests sparked by the widely condemned parliamentary elections of late 2011 was succeeded by a string of firings and censorship scandals at leading liberal publications, including Kommersant newspaper and Gazeta.ru, in what appeared to presage an inevitable crackdown.

Boris Timoshenko, department head at media freedoms campaign group Glasnost Defense Foundation, said the trend has affected a wide range of outlets.

“Media across the board are facing pressure. It’s indiscriminate,” Timoshenko said.

In 2012, investigative cable television station Sovershenno Sekretno (“Top Secret”) narrowly dodged closure after leading, state-owned cable operator Rostelecom dropped it from its roster. Channel representatives claimed the move was retribution for an interview with Lyudmila Narusova – the widow of Putin mentor Anatoly Sobchak and mother of Ksenia Sobchak – in which she expressed support for anti-government protesters.

Dozhd says it faced no problems at the time of its reporting on the street protests, but that it has felt the “close attention” of unspecified authorities ever since.

The channel may yet survive, but it could be at the cost of its credibility, Timoshenko said.

“One thing is unavoidable, and that’s the increase of self-censorship, both at Dozhd and in other media outlets,” he said.

The article was corrected to include Timoshenko's proper job title.