SOCHI, February 17 (Kevin O’Flynn and Howard Amos, RIA Novosti) – It was once the pride and joy of Stalinist Sochi, a grandiose palace for workers to recover from their labor in mines and factories, a mythical showcase resort for a society that didn’t truly exist.

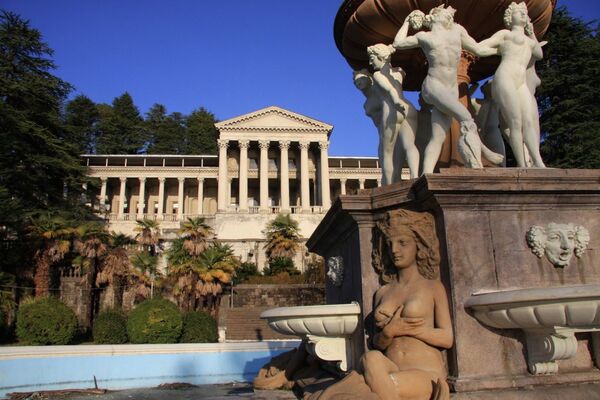

But the Ordzhonikidze Sanatorium stands empty now, a metal sign declaring “Entry Forbidden” strung across the vast sweep of the front gardens running down toward the Black Sea.

The imposing sanatorium, named after one of Stalin’s henchmen, shut down in 2010 for a massive overhaul, reportedly to be transformed into a luxury hotel. Four years on, there is little evidence of restoration work and no sign it will open soon – let alone for the Winter Olympic Games currently under way around Sochi, as originally planned.

Like other Soviet-era showpieces in Sochi, the shuttered spa symbolizes a city in transition: no longer drawing crowds with its state-subsidized sanatoria and attractions, but not yet modern enough to lure a new generation of tourists to its subtropical shores.

The Ordzhonikidze was “one of the most beautiful, ostentatious sanatoria,” said Alla Guseva, deputy head of research at the Sochi History Museum. Stretched across nearly a dozen buildings, it could once accommodate more than 600 people, who came to undergo treatment for everything from respiratory ailments to neurological disorders.

Now, a lone, grizzled security guard stands leaning on the upper balcony of the main building, looking out between two massive columns and warning people with cameras that photography is not allowed. His vigilance is as half-hearted as the two dogs’, more stray than guard, stretched out near him in the sun.

Local residents ignore the guard, the dogs and the no-entry sign. They rollerblade around the grounds and take photos in front of the huge, waterless fountain with an abundance of classical nudes at its center. A young man does pull-ups on a metal bar. Olympic volunteers in their colorful jackets walk by en route to their accommodations in neighboring buildings.

Communist Myth and Reality

The sanatorium is built on one of Sochi’s most valuable pieces of land, the late-afternoon sun lighting up its colonnaded facade before sinking into the sea. Before the revolution of 1917, noble families such as the Trubetskoys and the Volkonskys had dachas on this perfect spot, small and humble compared with the neoclassical might of the Ordzhonikidze.

Opened in 1936, the sanatorium was initially called Narkomtyazhprom, after the People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry, and workers, in particular miners, were sent on vacation there. (A miniature truck piled with coal is on display in the Sochi museum, a gift from grateful miners who had holidayed at the Soviet spa.)

It was built to look like a palace, a socialist version of the noble estates that the Bolsheviks had spent the previous two decades destroying, with huge columns, stone arches and sculptured gardens. It was a utopian sanatorium for a utopian city built to be shown to the rest of the Soviet Union and the world, said Guseva.

In a famous scene from the 1956 children’s film “Old Man Khottabych,” a genie appears at the sanatorium and, mistaking it for the palace of the shah, becomes frightened. But then a worker appears, relaxed after a spa procedure, and tells him, “No, it is a palace for workers and peasants.”

Sochi “is a city of myth,” said Guseva, and that myth was “partly realized in the architecture.”

The resort town was a paradise that had little in common with the rest of the country, not just in terms of climate.

“The city was well supplied, the shops were full, even though the country was hungry,” said Guseva. The idea was that “people would come and see all this and it would inspire them to build communism.”

But even vacationers were not immune to the repressions that shook the country in the 1930s. The most famous victim was Pyotr Mozharov, inventor of the first Izh motorbike, who was given a holiday at a Communist Party sanatorium in 1934 but never returned. His family received a letter saying he had killed himself, but Guseva doesn’t believe that version.

Even Sergo Ordzhonikidze, who became commissar for heavy industry in 1932, died under mysterious circumstances in 1937; official media reported the cause as a heart attack, though historians have speculated there was foul play. The sanatorium was renamed in his honor after his death.

Nostalgia, Volunteers and Foam Parties

What will happen to the Ordzhonikidze next is anyone’s guess, especially with the opacity that has surrounded much of the construction and reconstruction in Sochi.

Earlier this month, a pensioner named Tatyana snapped photos with a small film camera as she walked her dog around the grounds. She said she was photographing so she would have some memories of the sanatorium in case it disappeared.

She told the story of how Stalin decided to build such a grand sanatorium – a story told to journalists repeatedly during their time in Sochi. Supposedly, after Stalin saw an earlier sanatorium built for the army, he told Kliment Voroshilov, then defense commissar, that it was like a barracks and ordered the next sanatorium to resemble a palace.

“That’s just an old wives’ tale,” said Guseva, the museum official. “If Stalin didn’t like the architect, he would have been sent to Siberia.”

Instead, the architect went on to design Stalin’s dacha in Sochi.

The second grandest of the sanatorium’s buildings, where Olympic volunteers now live, was built after the war. But it is no ugly sister to the first. Soviet-themed reliefs adorn a facade resembling an Italian palazzo’s. Inside, an ornate wooden staircase leads up to small bedrooms and a grand dining room where the volunteers eat for free.

Back at the main building, a young events organizer named Natasha ushers a journalist up the grand staircase to show off preparations for a Valentine’s Day party organized by her company, Gatsby.

Inside, columns are clad in silver foil and tinsel, and printouts of pixelated classical nudes are getting pinned up on the walls. In the main room, giant letters spell out the word GATSBY. Tickets to the soiree cost 5,000 rubles (roughly $140).

Natasha shows a video on her phone of a previous party, an extravagant New Year’s bash that ran until 7 a.m. with a light show along the columns of the main building.

“We put foam in the fountain,” she says, smiling.

Guseva, of the history museum, said she had the impression that the presidential administration was now in charge of the sanatorium.

But asked if there are any limitations on what Gatsby can do there, Natasha just grinned: “We are in charge here.”