MOSCOW, November 11 (RIA Novosti), Ekaterina Blinova — Catalonia's symbolic independence vote on November 9 has shown strong support for secessionists, following the Scottish September referendum, which resulted in a victory for the "No" vote camp and preserved the unity of the UK.

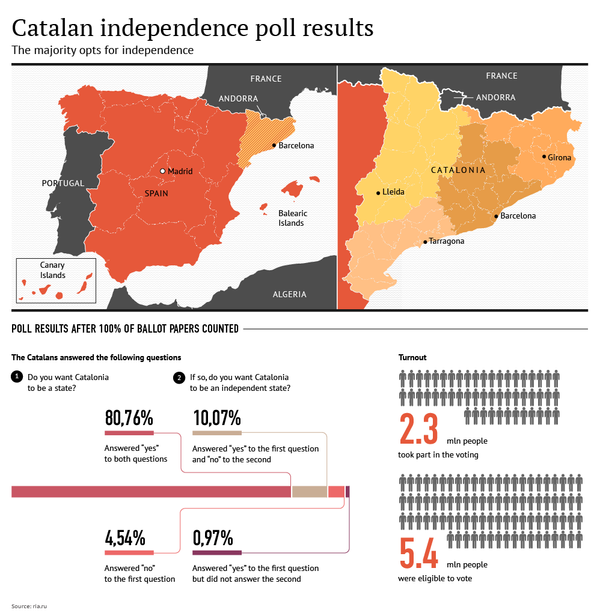

"80.72% of those Catalans who decided to take part in Sunday’s simulated referendum on secession from Spain voted "Yes-Yes" in favor of an independent Catalonia, in response to a two part question that asked them if they wanted Catalonia to be a state and if they wanted that state to be independent. While 10.1% of participants voted "Yes-No" for a Catalan state within Spain, 4.55% voted "No-No" for Catalonia to be neither a state nor independent," The Spain Report wrote on Monday, November 10.

Obviously the results of the nonbinding poll turned out to be more impressive for Catalan’s proponents of independence than those of Scotland's vote, where unionists won by 55.3 percent to 44.7 percent. Although the separatist movements of the two regions look similar, they also have certain differences.

Referendum movement

In 2011 the Scottish National Party (SNP), which backs the idea of Scottish sovereignty, gained the majority in Scotland's parliamentary elections and thus legally obtained a mandate to hold an independence referendum. After a series of consultations with the British government, the Edinburg Agreement (between the government of the United Kingdom and that of Scotland on a referendum on Scottish independence) was signed by Westminster and Holyrood on October 15, 2012. In accordance with the legislation, the two options for the future referendum were set: full independence or union. On June 27, 2013 the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013 was passed in the Scottish Parliament. Two months earlier, the official date for the vote had been set for September 18, 2014.

The decision "to go ahead with a plebiscite" regarding Catalonia's sovereignty issue was signed in the regional parliament on December 18, 2012. According to the agreement signed by Artur Mas, the Catalan president, Oriol Junqueras, as well as the leaders of the left-wing Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya and the center-right Convergència i Unió (CiU), the parties declared that they were committed to making all the formal preparations for a vote by December 31, 2013. However, in contrast with Westminster, Madrid fiercely opposed Catalan secession, denouncing the initiative as illegal. The stance of the Spanish government could be explained by the fact that the rise of the separatist movement had chronologically coincided with Spain's economic crisis. It is worth mentioning that Catalonia accounts for more than 18 percent of the state's economy and about 20 percent of its tax revenues.

The region's secession from Spain would inevitably hit the national economy. On September 27, 2014 Artur Mas signed a decree calling for a "non-referendum popular consultation" on the political future of Catalonia. Compared with the Scottish vote, the Catalan initiative was not expected to result in the immediate secession of the region (if approved by the majority of voters), but to serve as a legal basis for further negotiations with Madrid. In a response, the Spanish government made an appeal to the Spanish Constitutional Court in order to block any attempt of Catalonia to carry out the vote. Regardless of the protests of Madrid, the Catalan government held a symbolic plebiscite on November 9, 2014 in defiance of the Constitutional Court of Spain.

Economy

Both Scotland and Catalonia are considered to be contributors to their respective national economies. Catalonia, one of the largest and most industrialized regions of Spain, generates over 18 percent of the country’s national GDP. Scotland accounts for about 10 percent of the UK's GDP; although average per capita earnings there are less than the UK average, it generates offshore oil and produces shale oil and gas. Independence proponents insisted that both new sovereign states would improve their economic performance after secession. If Scotland gained independence, more than 90 percent of North Sea oil revenues would belong to the sovereign state, the "Yes" camp representatives pointed out, claiming that the Scottish oil and gas reserves would ensure that the country would then be able to generously fund social services rather than sharing these revenues with Scotland’s southern neighbors. Catalan nationalists emphasized that although their region lacked natural resources, they would be able to boost economic growth due to the region's industrial infrastructure, tourism and trade. Catalan’s secessionists claim that since 1986 about 9 percent of the region's annual revenue has been redistributed to less wealthy Spanish regions, denouncing the practice as unfair. A separate Catalonia would be richer and more prosperous than the rest of Spain, they underscore. However, the issue sparked a heated debate among economists, who emphasized that the slowdown of the European economy would apparently affect the development of the new states, adding that the EU membership of Catalonia and Scotland would be blocked by Spain and the UK, respectively.

History

Both the Catalan and Scottish secessionist movements have deep historic roots. The nations have their own cultural, ethnical and linguistic peculiarities. The union of Scotland and England was initially established in 1603 as the so-called Union of Crowns. The Treaty of Union and Acts of Union in 1707 finally formed the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland. However, Scotland retained its Presbyterian Church and legal system. For more than three hundred years, the two nations have co-existed as one state. In the end of the 19th century, a Scottish Home Rule Association was founded with the intension of gaining extended political powers. Eventually, Scotland obtained its own distinct administrative system: in 1895 a Scottish Grand Committee got the powers to discuss Scotland's legislation and in 1948 it started to consider bills relating to Scotland. Experts claim that discovery of oil in the North Sea in 1970 stimulated Scottish nationalists to push the devolution process forward. Finally, in 1999, Scotland re-established its own separate Parliament.

Whereas Scotland and England haven’t clashed militarily since the Jacobite rising of 1745, the Catalan separatists' centuries-old struggle with Spain continued into the 20th century, when the region saw heavy fighting during the Spanish Civil War. In 1640-1652, Catalan rebels, assisted by France, fought with the Spanish government in order to gain political rights. Catalans played an important role during the War of the Spanish Secession (1701-1714), supporting Charles VI, the Austrian Habsburg pretender for the Spanish throne. When Charles VI was defeated, the region lost its separate political institutions. In 1930s a coalition of Catalan nationalists, which claimed full independence from Spain, briefly regained autonomy status for the region, but lost it again under the rule of dictator Francisco Franco Bahamonde, who ruled from 1939 to 1975. Only in 1977 after the restoration of the monarchy, was Catalan autonomy ultimately restored. Remarkably, Catalonia's secessionist movement has expanded substantially since that time.

Assessing the results of the two referendums, experts have pointed out several key differences. For instance, they emphasize that the symbolic Catalan plebiscite was never expected to result in an immediate secession from Spain. While Scots were facing a serious and painful dilemma of whether to stay in the UK or leave, Catalans just expressed their opinion regarding the future of the country. Therefore, the number of the independence proponents taking part in the nonbinding poll was particularly high in Catalonia.

Other experts underscore that since the UK economy is doing better than those of many of the EU member-states, most Scots preferred extended political powers within a relatively flourishing British union rather than sovereignty. In contrast, the recent poor performance of the Spanish economy has forced Catalonia to seek economic independence: the wealthy region does not want to "sink" with the rest of the country and subsidize its less prosperous fellow regions.

Apparently, the historical legacy affected the secessionist movements as well: while Scotland has gained its regional legislative and executive powers through predominantly peaceful negotiations with the British government, Catalans have repeatedly faced strong opposition from Madrid. Additionally, anti-English sentiment among the Scots has been comparatively neighborly for several centuries, whereas heavy-handed authoritarian central rule only ended in Spain a generation ago and many still remember Franco’s repressions.

However, it is unlikely that "Spain's Constitution would be amended to allow for a US-style federal system in which Madrid might grant statehood to Catalonia," notes Los Angeles Times, citing Sofia Perez, a Spanish political scientist.

"More likely, I think, is a return to negotiations over the way in which Catalonia is financed, and some sort of compromise that would allow Catalonia to retain a larger share of the income taxes that are raised in Catalonia," Perez emphasized.

Catalan independence proponents call upon the Spanish government to allow them to decide their political future in accordance with internationally recognized democratic procedures, referring to referendums that have been held in Scotland and Quebec.