The online encyclopaedia is the sixth most popular website in the world and 15% of internet users look at it in every browsing session. But you can’t always believe what you read on the internet. And, that can even be true of the world’s biggest online encyclopaedia, Wikipedia.

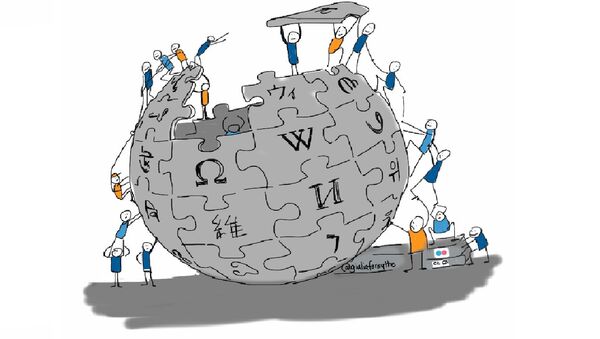

The site is operated by a leaderless collection of volunteers who work under pseudonyms. That’s different from the established encyclopaedic model, where advisory boards, editors, and contributors — selected from society’s highest intellectual ranks — would draw up a list of everything worth knowing and then create entries.

In fact, Wikipedia’s rules effectively discourage experts from contributing. Their work, like anyone else’s, can be completely, and anonymously, overwritten within minutes. Every article is amended several times a second and the anonymity creates a phoney equality, where experts and amateurs are put on the same footing.

So, although it’s a reliable source of simple facts and dates, authoritative entries on complicated subjects are elusive. Of the 1,000 articles that the project’s own volunteers have tagged as “forming the core of a good encyclopaedia”, most don’t earn even Wikipedia’s own middle-ranking quality scores.

Skewed Coverage

Wikipedia claims to be bias-free because everyone hooked up to the internet is a potential editor. In reality, however, the site only has about 70 000 active editors, and more than half of them count English as their first language.

That creates another problem: skewed coverage. The site is heavily biased towards subject matter that’s interesting to Western men.

“Our biggest issue is editor diversity,” admitted the site’s co-founded and promoter Jimmy Wales, speaking to Technology Review.

90% of Wikipedia’s editors are male, relatively young and tech-savvy. Naturally, they write about what they’re interested in.

A 2011 study from the University of Minnesota found that there is “categorically less coverage for content that’s categorically more interesting to women”.

Aaron Halfaker, a social scientist who works for the Wikimedia Foundation, calls this a “coverage bias”. It’s a bias not of how something is talked about, but of what is talked about

Aaron Halfaker says there’s a still more damaging bias built into Wikipedia. The site aims to be “verifiable”, not to tell the “truth”. What that means is that it’s constructed only from statements that can be “verified” and all sources are regarded as equal, regardless of their merit. If a peer-reviewed journal says one thing and a non-specialist newspaper report another, the Wikipedia entry is likely to cite them both, saying that the truth is disputed.

The Pitfalls of 'Verfiable'

This came about because editors were bickering about what to include. Using only verifiable sources meant arguments could be settled quickly – what to include was determined by what there was to cite.

That means that a lot of important material which the mainstream media doesn’t pick up on is simply absent. It’s not knowing or malicious, but the mainstream media effectively decides what facts appear in Wikipedia.

That becomes a problem when editors write about foreign countries, like Russia, in the English Wikipedia. Because the sources are not in English, they are not verifiable, so editors can’t get foreign viewpoints to stick.

Wikipedia is also susceptible to vandalism: transphobic and homophobic edits have appeared on various entries; the more popular the site becomes, the less likely users are to read its information critically.

Meanwhile, more worrying studies have shown that, on average, at least 50 per cent of doctors use Wikipedia in their practice. In 2013, medical-related content on Wikipedia was accessed five billion times, by patients and doctors — and medical content is as prone to inaccuracy as other entries. A group of Canadian doctors are campaigning to encourages patients and practitioners to question what they read on the website, and to use multiple sources.

Looking for Alternatives

In some ways, Wikipedia is most useful as a way of gauging what preoccupies people. A team of mathematicians, biologists and computer scientists are forecasting how and when diseases like influenza and dengue will spread, based purely on what people are searching for on Wikipedia. Recently they even showed how their algorithm could predict flu season in the United States.

In the US, where the site is most popular, there are an increasing number of alternatives. Scholarpedia, for example, is like a mirror site but the difference is it’s written by scholars who have to be invited to contribute. Citizendium aims to be like Wikipedia but without anonymity.

And, there are sites that address its bias with a bias of their own. Conservapedia is a conservative, Christian-influenced encyclopeadia that was created as an antidote to what is calls Wikipedia’s “left wing, liberal skew”. The information is free of foul language and explicit sexual references.

Meanwhile – aware that Wikipedia is beginning to have a material impact on how people view global geography and history — other states are trying to even out the distribution of knowledge.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library is creating a Russian alternative – to counter omissions and inaccuracies on Wikipedia’s entries about the country. The American Presidency Project is offering something similar. And Cuba and China each have established alternatives.