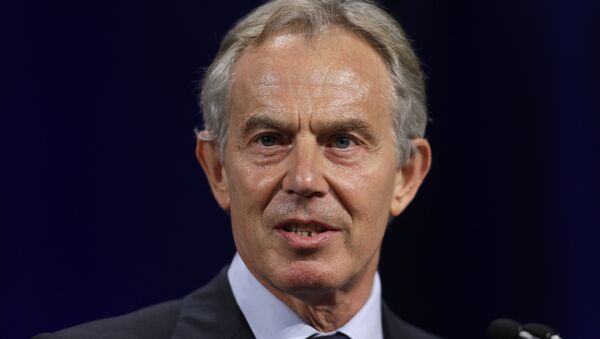

Blair's government, in the run-up to invasion, faced down one of the biggest popular uprisings Britain had seen against going to war against Saddam Hussein's regime. Blair agreed with the US President, George W. Bush's view that the Iraqi dictator had weapons of mass destruction that could be used against British targets.

Bush and Blair held private talks, the details of which have been kept confidential, but which — many believe — would lay bare the agreement Blair made with Bush to follow the US into a war for regime change in Iraq and lay Blair open to charges of war crimes.

Lord Dykes, told the House of Lords this week that: "more and more people think that it is some kind of attempt to prolong the agony for Mr Blair facing possible war crimes charges".

The alleged cover-up of the findings of the Chilcot inquiry into the lessons to be learned from going to war in Iraq drew one former foreign secretary to describe it as a "scandal". Lord Hurd told the Lords: "This has dragged on beyond the questions of mere negligence and forgivable delay; it is becoming a scandal. This is not a matter of trivial importance; it is something to which a large number of people in this country look anxiously for the truth".

Background: Blair's Dodgy Dossiers

Blair's government published a dossier of evidence, in September 2002 that stated there was evidence that Saddam Hussein's regime had "military plans for the use of chemical and biological weapons. Some of these weapons are deployable within 45 minutes of an order to use them". The 45 minute claim made all the front pages, with the Sun newspaper proclaiming: "Brits 45mins from doom".

For several weeks its contents were debated and criticised. The 45 minute claim was widely disputed and eventually led the BBC journalist Andrew Gilligan to report that the claim was being dismissed by senior intelligence staff and that the British government knew the claim was wrong before publishing the dossier.

The broadcast of his report led to the controversial outing of his source, Dr David Kelly, and his eventual apparent suicide, though this is widely disputed. Kelly was found dead two days after an aggressive grilling at the hands of the House of Commons foreign affairs select committee.

In February 2003, Blair's team published a second dossier called Iraq — Its Infrastructure of Concealment, Deception and Intimidation. It made further claims about the prevalence of Saddam Hussein's WMD capabilities, mostly based on an article by (then) graduate student Ibrahim al-Marashi, with key extracts being "hardened up" to improve the case for war.

Feelings were running high in Britain (and around the world) and in February 2003, police estimated at least 750,000 marched on London in protest at the war-mongering, although organisers put the figure closer to two million. It was nonetheless, the biggest mass demonstration Britain had seen in decades.

Blair and Bush go to War in Iraq

On March 20 2003, the US and UK forces began the invasion that led to the eventual downfall of Saddam Hussein and his regime. Politicians from all sides of parliament in the UK called for an inquiry into what deals Tony Blair had made with then US President George W. Bush.

Finally, after years of pressure to uncover the deals made between Bush and Blair, the then British Prime Minister Gordon Brown caved in to public pressure and called for an inquiry which was launched in July 2009 chaired by Sir John Chilcot. Its terms of reference were to: "consider the period from the summer of 2001 to the end of July 2009, embracing the run-up to the conflict in Iraq, the military action and its aftermath….. the way decisions were made and actions taken, to establish, as accurately as possible, what happened and to identify the lessons that can be learned".

Between November 2009 and February 2011, the inquiry heard from hundreds of witnesses and took in thousands of documents in an effort to discover the background to the decision to go to war with Iraq.

So far, the £7.4 million inquiry has yet to report. Although Sir John Chilcot wanted as much as possible of the evidence to be made public, Whitehall mandarins and their political masters have been tussling to redact as much as they can to keep key evidence secret and to protect key people who took decisions, not least Tony Blair and the conversations he had with Bush and whether Blair lied to parliament. Many say the finding — if fully published — will show Blair acted illegally and committed war crimes.

The inquiry report has yet to be published. We may never know the whole truth. And Britain has yet to learn its lesson. But there is still a chance that Blair may finally be brought to justice.