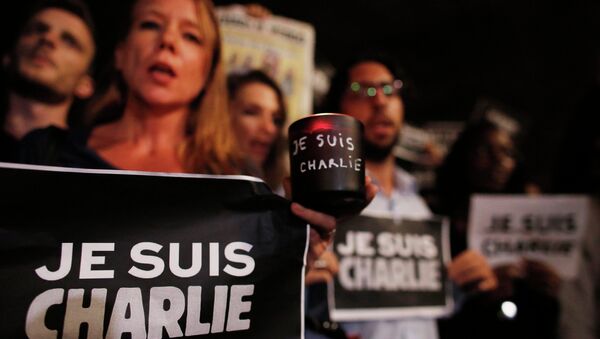

MOSCOW, January 15 (Sputnik) — In reaction to last week's deadly attack on the controversial satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, millions of outraged, grief-stricken people in France, throughout Europe and around the world have taken up the defiant 'Je suis Charlie' (I am Charlie) slogan, symbolizing their sympathy toward the victims and their support for the right to free speech. Others, while unequivocally denouncing the attacks, have refused to join in, and on the contrary, have expressed the view that 'Je ne suis pas Charlie' (I am not Charlie). Sputnik asks why these people, whose ranks include ordinary people, journalists and academics alike, have taken up the contrarian position they have, and the rationale and logic behind their decision.

Some journalists, political scientists and social commentators on the I am not Charlie side have expressed that their opposition to the I am Charlie campaign stems at least in part from the fact that while the killings were indeed horrendous, there is nevertheless something to be said about limitations to free speech.

Hasan also points out that even the oft-vicious satire of Charlie Hebdo would never print cartoons mocking the Holocaust, or the attacks of 9/11, and rightly so. And his point raises the important question about the difference between freedom of expression and simply being offensive, and the right to make homophobic, racist, sexist or otherwise hurtful remarks which, in many cases have legal ramifications even in countries most proud of their citizens' ostensible right to free speech.

In his opinion piece for the London Evening Standard, Sam Leith puts the matter more bluntly, noting that "free speech is…abridged de facto," and that while "'self-censorship' gets bad press…it's sometimes good manners. The law may not stop me calling you a n*****, but that doesn’t mean I take an important stand for liberty by doing so."

In a more philosophical piece for the news and political analysis source Mondoweiss entitled "The moral hysteria of Je suis Charlie", Oxford philosopher Brian Klug proposes an interesting thought experiment, asking readers to imagine what might happen if a man joined last week's Paris unity rally wearing a badge saying 'Je suis Cherif' (one of the gunmen responsible for the attack), together with a witty placard mocking the dead journalists. "How would the crowd have reacted? Would they have seen this lone individual as a hero, standing up for liberty and freedom of speech? Or would they have been profoundly offended?" Klug suggests that the reality is that such a person "would have been lucky to get away with his life [intact]."

Bringing Klug's thought experiment vividly to life was the news earlier this week on the arrest of controversial French comic Diedudonne, accused of anti-Semitism and showing support for terrorism. In a crude attempt to parody the 'Je suis Charlie' slogan, the comedian wrote on his Facebook account that "tonight, as far as I'm concerned, I feel like Charlie Coulibaly" (one of the gunmen at the Jewish supermarket siege that followed shortly after the Charlie Hebdo attack).

Islamophobia and Incitement of Further Radicalism

Express & Star contributor Peter Rhodes echos Helmi's sentiment, noting that while he would "march in rage and despair at the premeditated slaughter of fellow journalists," the offensive cartoons only work to offend "the very people whose help we most need to defeat the psychopaths of jihadism." And Hasan notes in his New Statesman piece that the grotesque perceived right to offend would only play into terrorists "bloodstained hands by dividing and demonizing," characterizing the division as "the enlightened and liberal west v the backward, barbaric Muslims." Pointing out the absurdity of the situation, he notes the fact that the attackers were disaffected and radicalized "not by drawings of the Prophet in Europe in 2006 or 2011, [but] as it turns out, by images of US torture in Iraq in 2004."

In one of a series of internal emails written in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack made public by the National Review, Al Jazeera English language editor Salah-Aldeen Khadr tells his staff that while "defending freedom of expression in the face of oppression is one thing; insisting on the right to be obnoxious and offensive just because you can is infantile." Khadr notes that "baiting extremists isn't bravely defiant when your manner of doing so is more significant in offending millions of moderate people as well."

I am against ALL murder but #IamNOTcharlie I am not #Islamophobic Why must we defend their #hatespeech in order to offer our sympathies?

— Atlanta Palestine (@AtlPalestine) 7 января 2015

What happened at Charlie Hebdo was horrible but does NOT excuse their own racism & bigotry. #jenesuispascharlie (tw) http://t.co/xwyiRTorZ7

— Shelly T. (@mizshellytee) 8 января 2015

In her article "If je ne suis pas Charlie, am I a bad person?", Roxane Gay of The Guardian expresses the dangers buried within the "you are either with us or against us" mentality created by the 'Je suis Charlie' campaign. "Demands for solidarity can quickly turn into demands for groupthink, making it difficult to express nuance," Gay explains. The journalist notes that the social network-based gesture of solidarity is a method of sharing "our anger, our fear, or devastation without having to face that we may not be able to do much more" in a world where we feel so powerless. "Life moves quickly but, sometimes, consideration does not. And yet, we insist that people provide an immediate response, or immediate agreement, a universal, immediate me-too –as though we don’t want people to pause at all, to consider what they are weighing in on. We don’t want to complicate our sorrow or outrage when it is easier to experience these emotions in their simplest, purest states."

#JeSuisCharlie vs #JeNeSuisPasCharlie is the polarisation they want you to fall for and feed into.

— DIRAC (@Irimbere) 8 января 2015

Ultimately there are many reasons behind the 'Je ne suis pas Charlie' campaign, from demands for the recognition that freedom of expression is not absolute and without consequence, to fears of a backlash against ordinary Muslims, and of an intensification in the "us vs. them" mentality that works only to strengthen the extremists on both sides.