“I was living literally in terror,” writes Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a prisoner in the U.S. detention facility at Guantanamo Bay. “I don’t remember having slept one night quietly; for the next 70 days to come I wouldn’t know the sweetness of sleeping.”

In “1984,” Winston Smith is tortured out of his convictions in Room 101 in the Ministry of Truth. In “A Clockwork Orange,” the state uses psychological punishment to reform its criminals. In “Fahrenheit 451,” the government burns – not redacts – books to dumb down the population.

These are all fictional works, but what makes Slahi’s account so gut-wrenching – and what shot it into Amazon’s top 100 best-selling books list after only a day of publication – is the reality of it.

A native of Mauritania, Slahi fought with mujahideen rebels in Afghanistan during the 1990s.

Following 9/11, he was detained for questioning about the Millennium Plot, a series of planned, though thwarted, bombings. After being transferred to various CIA “black sites,” Slahi was taken to Guantanamo in August of 2002.

He is one of the longest serving inmates. Despite a 2010 federal ruling which said the military was unlawfully holding Slahi, there he remains.

The book describes in intimate detail the hardships of life inside the controversial facility. Names of inmates were taken away, replaced with numbers. All personal comfort items were removed. Books were taken away. The Quran. Basic elements of hygiene were denied.

“I was deprived of my toothpaste. I was deprived of the roll of toilet paper I had,” the book reads.

Slahi also describes the often malicious treatment he received from Guantanamo’s guards.

“When I failed to give him an answer he wanted to hear, he made me stand up, with my back bent because my hands were shackled with my feet and waist and locked to the floor…he kept me hurt during his lunch, which took at least two to three hours.”

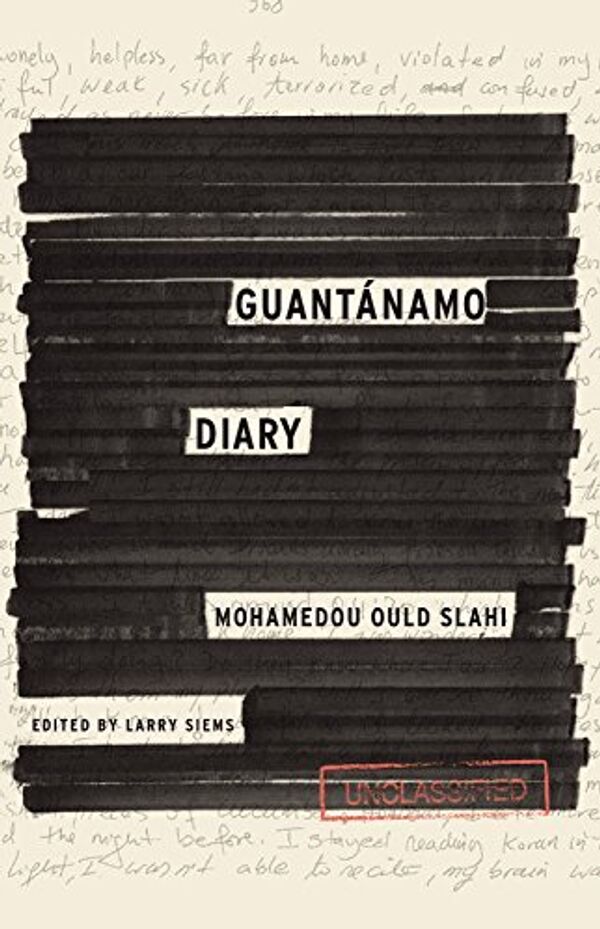

Finished in 2006, the memoir was considered classified by the U.S. government. It was only cleared for publication after the American Civil Liberties Union worked with the government to censor any classified material.

“It is the first and only book to come out of Guantanamo, and written while in Guantanamo,” the book’s editor, Larry Siems, told Sputnik. “I think it really opens up the world that the U.S. government has tried to keep secret for 13 years.”

During his State of the Union address Tuesday night, President Obama reaffirmed his old pledge to close the prison.

“It makes no sense to spend three million dollars per prisoner to keep open a prison that the world condemns and terrorists use to recruit,” he said.

The unflattering realities depicted in this book could be the spark that mobilizes public opinion and finally forces the administration to make good on its word.

“We will all be free to see the ‘Guantanamo Diary’ for what it is: an account of one man’s odyssey through an increasingly borderless and anxious world,” Siems said.

For all its allusions to fictional works, “Guantanamo Diary” may bear strongest similarities to the 2001 French novel, “This Blinding Absence of Light.” Based on real-life accounts, the book relays the account of a former inmate in Tazmamart, a Moroccan prison where King Hassan II kept political dissidents on the bare edge of life. Thousands were jailed, killed, or mysteriously vanished.

The United States were strong allies with King Hassan II during the Cold War. Perhaps some of his practices rubbed off.