"We can't wait to turn Pluto into a real world, instead of just a little pixelated blob," project scientist Hal Weaver of Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory told AP. "New Horizons has been a mission of delayed gratification in many respects, and it's finally happening now."

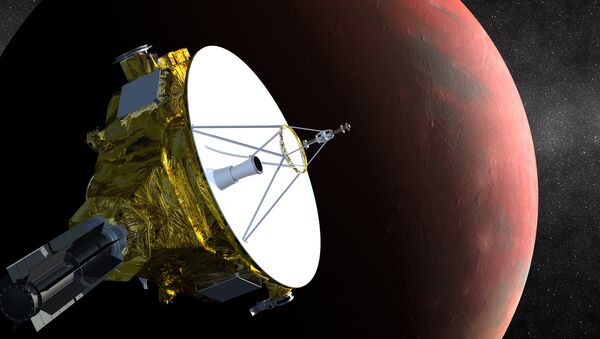

The $700 million New Horizons mission was launched from Cape Canaveral in January 2006, and upon completion will mean that Pluto joins the other eight planets of the solar system to have been explored by humans. The Voyager 2 spacecraft completed close flybys of Jupiter in 1979, Saturn in 1981, Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

Before May, NASA scientists will use images from the spacecraft in order to manoeuvre it to its target point. "We need to refine our knowledge of where Pluto will be when New Horizons flies past it," said Mark Holdridge, the New Horizons encounter mission manager from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory said earlier this month. "The flyby timing also has to be exact, because the computer commands that will orient the spacecraft and point the science instruments are based on precisely knowing the time we pass Pluto – which these images will help us determine."

Pluto, which was demoted from planetary status in 2006, lies in the Kuiper belt, a ring-shaped region of icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune. Pluto and Eris are the best known of the icy dwarf planets within it, of which NASA believes there could be hundreds more.