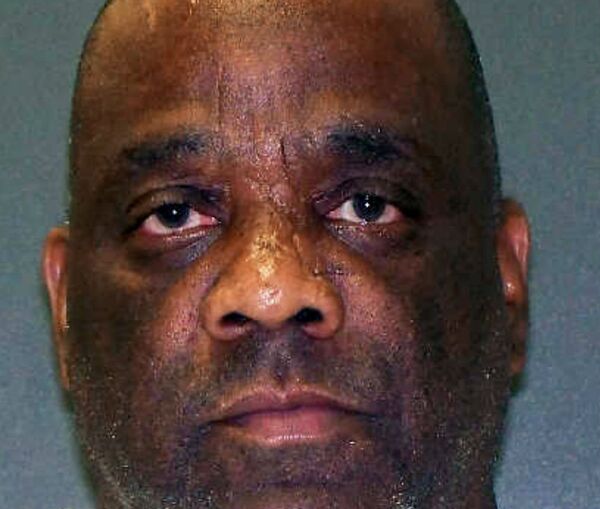

"Ladd's deficits are well documented, debilitating and significant," said Brian Stull, a senior staff lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union Capital Punishment Project, in an unsuccessful attempt to persuade the the high court that Ladd was unfit for execution on Thursday.

— Tasneem N (@TasneemN) January 30, 2015

Ladd had been convicted of murdering a 38-year-old Texas woman, Vicki Ann Garner, by beating her head in with a hammer and then setting her on fire almost two decades ago. He had been out on parole at the time of the murder after a previous conviction for triple homicide.

As proof of Ladd's mental disability, his lawyers had presented a psychiatric evaluation from 1970 when he was a 13 year old in juvenile custody that put his IQ at 67 and described him as "fairly obviously retarded." Courts have often used an IQ of 70 as a cut-off line to determine mental disability.

Despite that evaluation, "each court that has reviewed Ladd's claim has determined that Ladd is not intellectually disabled," wrote Kelli Weaver, a Texas attorney general, in a court filing.

In 2003, Ladd was hours from execution when a last minute decision to hear the evidence from juvenile records was granted. Ultimately, though, the appeal failed and the Supreme Court last year decided not to hear a review of the case.

— Rev. Dr. Jeff Hood (@revjeffhood) January 29, 2015

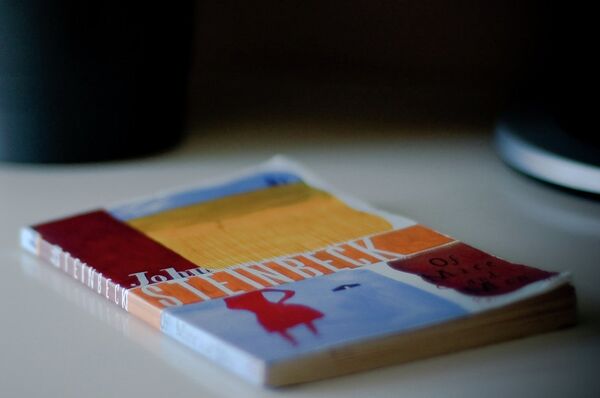

Retardation Criteria Based on Of Mice and Men

Ladd’s death comes on the heels of Georgia’s execution of Warren Hill on Tuesday after the Supreme Court denied a stay despite the fact several medical experts had examined Hill and found him to be intellectually disabled.

The Supreme Court decided in the 2002 case Atkins v. Virginia that it is unconstitutional to execute the mentally disabled as it would violate the eighth amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. However, the court left it up to the states to determine how to define the disability.

“There is no question that Georgia’s ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ standard violates the Eighth Amendment," Hill’s attorney argued in a statement after his stay was also denied by the Supreme Court.

As for Texas’ standard, rather than relying on widely accepted medical consensus and established diagnostic tests, the state cites the "level and degree of [mental disability] at which a consensus of Texas citizens" would deem someone unfit for the death penalty.

To illustrate how Texas citizens might reach a consensus, Texas Court of Criminal Appeals Judge Cathy Cochran used the example of Lennie Small, a fictional character in John Steinbeck's short novel, Of Mice and Men.

“Most Texas citizens might agree that Steinbeck’s Lennie should, by virtue of his lack of reasoning ability and adaptive skills, be exempt” from execution, wrote Cochran in her 2004 opinion.

She went on to outline seven factors, referred to as “Briseño Factors”, for evaluating death row appeals.

“Things like: Is this someone who’s a leader or a follower? Is this someone who can lie effectively and spin a good story and keep things straight? You can’t spin a good lie and keep it going if you can’t remember things for very long, if you’re not coherent, if you can’t tell a clear story.”

This makes Texas’ definition for who is exempt from the death penalty narrower than most. And the court’s explicit statement that some mentally disabled people should qualify came as a shock even to death penalty advocates at the time.

Stull pointed out that the Supreme Court clearly referenced established medical and psychiatric evaluations of the kind that could have been used to evaluate Ladd.

"But the Texas courts insist on severely misjudging his intellectual capacity, relying on standards for gauging intelligence crafted from 'Of Mice and Men' and other sources that have nothing to do with science or medicine. Robert Ladd's fate shouldn't depend on a novella," said Stull.

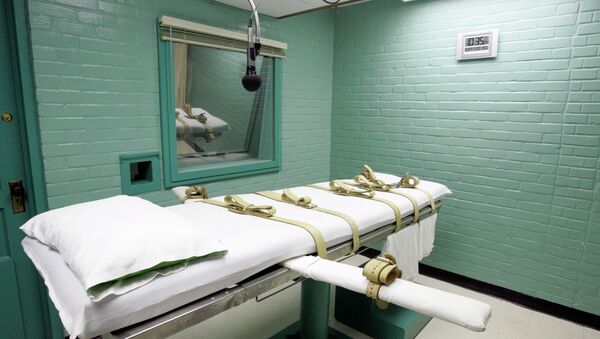

Ladd is the second inmate executed this year in Texas, the nation’s most active death penalty state.