Immigrants have long been a favorite scapegoat for all sorts of social problems, and the recent measles outbreak that began at Disneyland is no exception. Public figures, from Rush Limbaugh to possible presidential hopeful Ben Carson have tried to claim there’s a connection between immigrants and the recent resurgence of measles in the US.

“We have to account for the fact that we now have people coming into the country, sometimes undocumented people, who perhaps have diseases that we had under control,” Carson told CNN’s Jake Tapper in a Feb. 3 interview. “So now we need to be doubly vigilant about making sure that we immunize our people to keep them from getting diseases that once were under control.”

Though it’s likely that the recent outbreak started with someone overseas — the Disneyland parks do attract tourists from all over the world — there’s been no evidence to link it to immigrants, documented or otherwise. The central American countries that the recent surge of child migrants have been coming from have vaccination rates comparable to the US’ rate of 91%: El Salvador's was 94%, Guatemala's 85% and Honduras' 89%, according to the most recent World Health Organization data.

Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported that the strain identified in the California outbreak is identical to a strain that caused an outbreak in the Philippines in 2014, but which also has been spotted in 14 other countries in recent months.

The disease could also easily have been brought back by an American who had travelled overseas. A measles outbreak in 2014 in Ohio, for example, was found to have started among a group of unvaccinated Amish who did volunteer work in the Philippines during their outbreak. Measles can be carried by a person for several days before symptoms begin to appear.

Falling Vaccination Rates the Problem, not Immigrants

Meanwhile, cases originating with the Disneyland outbreak have been documented both south and north of the border. Though officials in Mexico reported 2 related cases early in the outbreak, health officials in Quebec’s Lanaudiere region also confirmed related cases on Feb. 3.

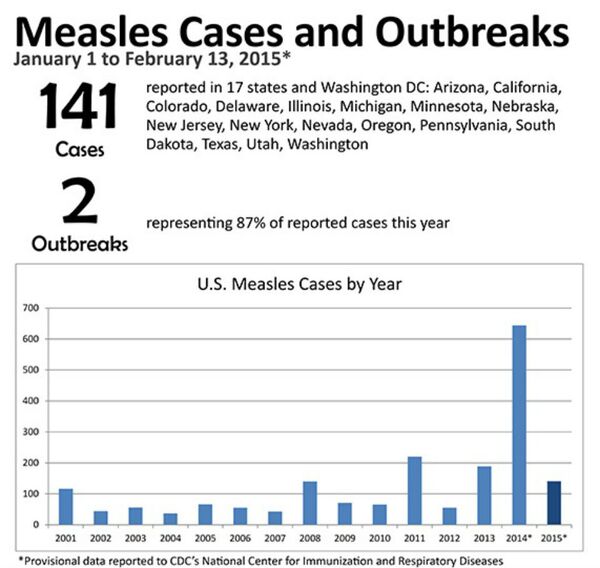

Most of the original cases in Southern California (and now the 17 states to which the outbreak has spread) were diagnosed in those who had simply not been vaccinated. Of the 110 cases confirmed as of Feb. 13, 45% were unvaccinated, and 43% had vaccination histories that were unknown or unverifiable. The ten cases in Quebec were also among a family who had remained unvaccinated for religious reasons.

"This is not a problem of the measles vaccine not working. It's a problem of the measles vaccine not being used," Dr. Anne Schuchat of the CDC told reporters in January. "Measles can be a very serious disease and people need to be vaccinated."

Last year the US saw a spike in the number of confirmed measles cases, with a reported 644 in 2014, the CDC reported. Nearly all of these cases have been associated with international travel by unvaccinated people.

Measles typically starts with fever, runny nose, red eyes and a cough, with a red rash appearing after a few days that starts at the face and moves downwards on the body.