In the summer of 1946, two married couples were hanged from an oak tree along the Apalachee River, near the town of Monroe, 60 miles east of Atlanta, Georgia. Overlooking the Moore’s Ford Bridge, the four African Americans – George and May Murray Dorsey, and Dorothy and Roger Malcom – were shot sixty times by a mob of 15-20 white men.

This was the last mass lynching in American history, and even caused an outraged President Truman to create the President’s Commission on Civil Rights. But despite the case’s high-profile, an abundance of eyewitness testimony, and a thorough FBI investigation, no one was ever held accountable. More astounding still, no one was ever even tried for the crime. A 23-person grand jury – which included two black members – declined to indict a single person.

For his new book, historian Anthony Pitch requested court documents from the grand jury hearing. But a filing from the US Department of Justice says that any transcripts from the case have disappeared.

“It is apparent that if there were such transcripts, (which the government has no reason to believe there were not), they have been either lost or destroyed at some unknown time in the past,” George Peterson, an assistant US attorney, wrote in the filing.

“The FBI does not currently have the transcripts,” federal judge Marc Treadwell wrote in a legal order last August. “In short, there is no evidence that the grand jury transcripts or any other grand jury records exist.”

The disappearance of records from such a prominent case leave many questioning just who was involved in the 1946 murders, and how deeply entrenched white power managed to become in the post-war South.

Suspects and Conspirators

“I don’t believe for one minute that these records were actually lost,” Edward Dubose, a board member for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, told the Guardian. “Our efforts to bring light on this case in pursuit of justice have been thwarted at every turn. There are people who do not want the truth to come out.”

Dubose is not alone. Civil rights activists have long claimed that local law enforcement worked to hinder the FBI’s investigation in 1946. Even J. Edgar Hoover, infamous head of the FBI for over thirty years, blamed an “iron curtain” of endorsed intimidation which scared other white residents into keeping quiet.

According to the book Fire in a Canebrake, by Laura Wexler, Hoover was deeply suspicious that the local sheriff’s office was trying to protect one of their own who may have been a part of the lynch mob.

Some even accused the FBI of undermining its own investigation.

“To my mind it is unbelievable that the FBI couldn’t find a member of that mob,” future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall said at the time, according to Wexler. Indeed, Hoover would gain a reputation in later years for working against “subversive elements” within the civil rights movement, even trying to sabotage the credibility of Martin Luther King Jr.

But according to files released through a 2007 Freedom of Information Act request, the investigation also eyed then-governor Eugene Talmadge.

The Power of the Vote

During reconstruction, many Southern states enacted various voting laws, intended to marginalize newly freed slaves. Poll taxes and literacy tests were two such examples, but there were also more blatantly racist white-only primary elections.

These primaries were banned by a Supreme Court ruling in 1944, and that severely threatened Talmadge’s 1946 reelection.

According to the Guardian, Talmadge visited Monroe only days before the lynching occurred, and files obtained by the Associated Press report that Talmadge had been heard offering protection to anyone “taking care of negro.”

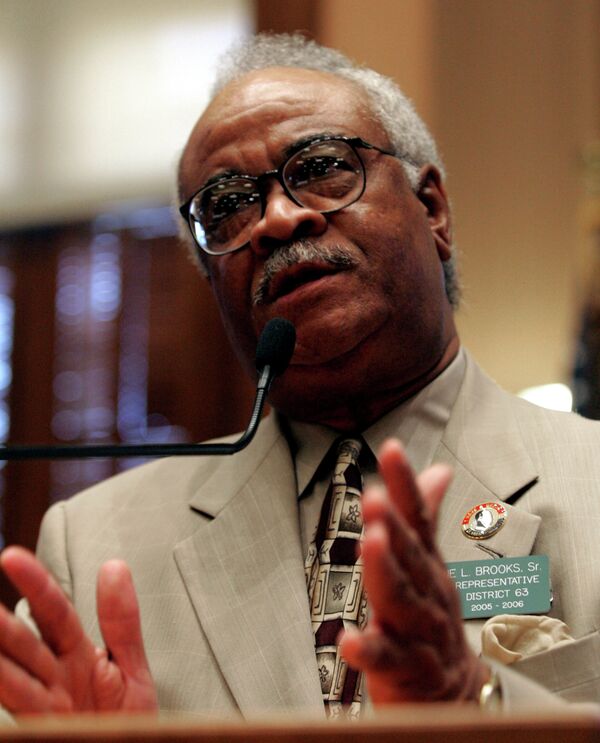

“This was all about voting,” Georgia state representative Tyrone Brooks told the Guardian. “Blacks were being killed trying to vote, and we had an uprising of the KKK – with the approval of Talmadge – trying to stop them.”

An Ongoing Investigation

Civil rights activists have recently provided the FBI with a list of still-living, potential suspects. While the disappearance – or destruction – of the original court documents will certainly prove challenging for investigators, closure is important.

“There is a lot of pain, a lot frustration and a lot of disappointment,” Brooks said. “Because it has always said – like other cases have suggested more recently – that black lives don’t matter.”

Those more recent cases, of course, being the wave of police killings of unarmed black men. Grand jury decisions not to indict responsible parties caused protests across the United States, most notably in Ferguson, Missouri, after Darren Wilson escaped indictment for the death of Michael Brown.