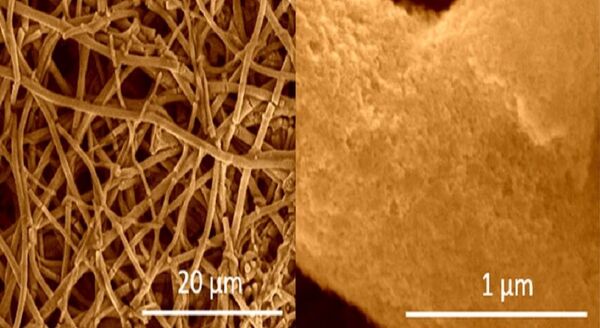

The “paper-like” material was developed at the University of California, Riverside’s Bourns College of Engineering and is made up of silicon nano-fibers that form a sort of sponge.

Lithium ion batteries are some of the most common rechargeable batteries used in consumer electronics. They are conventionally produced using a mixture that includes graphite, but scientists are experimenting with silicon since it has a much greater specific capacity — the electrical charge per unit weight of the battery — than graphite.

In this case, the material is produced by a process known as electro-spinning, whereby a solution of primarily tetraethyl orthosilicate is placed inside a rotating drum with 20,000 to 40,000 volts of electricity. Exposure to magnesium vapor then produces the silicon fibers.

The nanofiber structure allows the battery to be cycled through many more times than traditional lithium-ion batteries, which can degrade more quickly and expand in volume.

“Eliminating the need for metal current collectors and inactive polymer binders while switching to an energy dense material such as silicon will significantly boost the range capabilities of electric vehicles,” Zach Favors, one of the graduate students working on the project, told said.

Mihri Ozkan, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and Cengiz S. Ozkan, a professor of mechanical engineering led a team of six graduate students. Their findings, summarized in a paper “Towards Scalable Binderless Electrodes,” were published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Scalability of the this type of battery has long been a problem for manufacturing, but the team was able to produce several grams of the nanofibers, which are 100 times thinner than human hair, in a laboratory, rather than an industrial, setting.