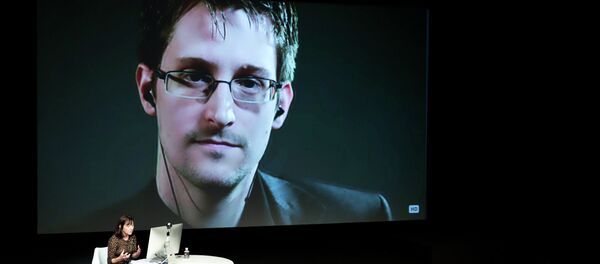

That information is revealed in a 2010 document from British intelligence agency Government Communications Headquarters. The top-secret report is the latest to be leaked by National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden.

The document was made public on journalist Glenn Greenwald’s website, the Intercept. Greenwald has been publishing such documents since Snowden first leaked them in June 2013.

A joint unit of operatives from the NSA and the GCHQ committed the breach, the Intercept reported. The hack gave the agencies the ability to secretly monitor a large portion of the world’s cellular communications, including both voice and data.

The agencies’ target was Gemalto, a multinational firm incorporated in the Netherlands that makes the chips used in mobile phones and next-generation credit cards, the Intercept reported. Among its clients are AT&T, T-Mobile, Verizon, Sprint and some 450 wireless network providers around the world.

Gemalto operates in 85 countries, including the US, and has more than 40 manufacturing facilities. The company produces approximately 2 billion SIM cards per year.

According to documents published on The Intercept, GCHQ – with support from the NSA – covertly mined the private communications of engineers and other Gemalto employees in multiple countries.

“I’m disturbed, quite concerned that this has happened,” Paul Beverly, a Gemalto executive vice president, told the Intercept. The most important thing for me is to understand exactly how this was done, so we can take every measure to ensure that it doesn’t happen again, and also to make sure that there’s no impact on the telecom operators that we have served in a very trusted manner for many years. What I want to understand is what sort of ramifications it has, or could have, on any of our customers."

— Ali Gharib (@Ali_Gharib) February 19, 2015

Top privacy advocates and security experts say that stealing encryption keys from major wireless network providers is equivalent to obtaining the master ring that holds the keys to every apartment in a building.

“Once you have the keys, decrypting traffic is trivial,” Christopher Soghoian, the principal technologist for the American Civil Liberties Union, told the Intercept. “The news of this key theft will send a shock wave through the security community.”

After being alerted to the hacks, Gemalto’s internal security team began to investigate, but were unable to find no evidence of the breach.

Beverly, the Gemalto VP, said neither the NSA nor the GCHQ requested access to Gemalto-manufactured encryption keys.

The team of NSA and GCHQ hackers that committed the breach, the Mobile Handset Exploitation Team, was formed in April 2010 and its existence was unknown until now, the Intercept reported.

One of its main missions was to penetrate computer networks of corporations that manufacture SIM cards, as well as those of wireless network providers.

The intelligence agencies now have the ability to intercept and decrypt communications without alerting the wireless network provider, the foreign government or the individual user that they have been targeted, the Intercept reported.

“Gaining access to a database of keys is pretty much game over for cellular encryption,” Matthew Green, a cryptography specialist at the Johns Hopkins Information Security Institute, told the Intercept.

He added that the massive key theft is “bad news for phone security. Really bad news.”