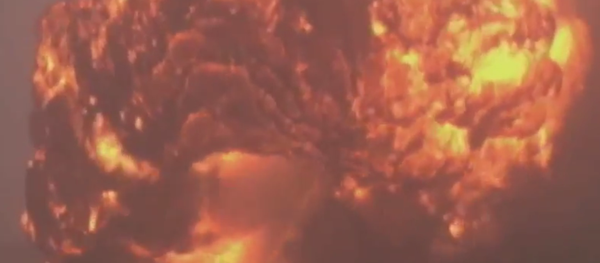

On Monday, a train hauling 100 tankers of crude oil derailed in West Virginia. The violent crash sent one tanker into a house, another into a river and punctured several more, eventually causing 19 of them to become engulfed in flames.

The fiery accident, which forced residents of two small towns to evacuate their homes, is renewing questions about whether such tankers are safe enough to carry crude.

— Matt Heckel (@WSAZmattheckel) February 17, 2015

Since 2005, the US has seen a 400% rise in the transportation of crude oil. Move all that black gold via tankers that are not designed to carry flammable crude oil, and you get sections of railway that light up like a string of Christmas lights.

In 2013, a train derailment in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, resulted in such a scene, with several tankers bursting into flames. Many of the tankers involved in that crash were DOT-111s – which are not equipped to transport crude, but regularly do so on North American rail lines, Popular Mechanics reported.

In 2009, the US National Transportation Safety Board designated the DOT-111 as inadequate to carry ethanol and crude oil, mainly because of its inability to prevent a puncture in the event of a crash.

But, the NTSB's recommendations are simply that – recommendations, which are not legally binding anywhere in North America.

More than 100,000 DOT-111s were transporting crude across American and Canadian rails when the Quebec accident occurred, and still are today, Popular Mechanics reported.

DOT-111s were not involved in the West Virginia crash, a fact that the railway company that owns Monday's crashed tankers were quick to point out. Those tankers were CPC-1232s, which are tougher, reinforced versions of the DOT-111s.

But Monday’s crash proves that the reinforcements, which were put in place following the NTSB’s 2009 warning, are not sufficient to prevent punctures.

The CPC-1232s are being used more and more, and eventually will replace the older DOT-111 models. But both tankers have 7/16-inch-thick shells, which still fall short of the 9/16-inch mark that US regulators say would decrease the likelihood of puncturing during a crash.